AUSTIN, Texas —Scientists at The University of Texas at Austin can now map what happens neurologically when new information influences a person to change his or her mind, a finding that offers more insight into the mechanics of learning.

The study, which was published Nov. 1 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, examined how dynamic shifts in a person’s knowledge are updated in the brain and impact decision making.

“At a fundamental level, it is difficult to measure what someone knows,” said co-author and psychology associate professor Alison Preston. “In our new paper, we employ brain decoding techniques that allow us deeper insight into the knowledge people have available to make decisions. We were able to measure when a person’s knowledge changes to reflect new goals or opinions.”

The process, researchers said, involves two components of the brain working together to update and “bias” conceptual knowledge with new information to form new ideas.

“How we reconcile that new information with our prior knowledge is the essence of learning. And, understanding how that process happens in the brain is the key to solving the puzzle of why learning sometimes fails and how to put learning back on track,” said the study’s lead author Michael Mack, who was a postdoctoral researcher in the Center for Learning & Memory.

In the study, researchers monitored neural activity while participants learned to classify a group of images in two different ways. First participants had to learn how to conceptualize the group of images, or determine how the images were similar to each other based on similar features. Once they grouped the images, participants were then asked to switch their attention to other features within the images and group them based on these similarities instead.

“By holding the stimuli constant and varying which features should be attended to across tasks, the features that were once relevant become irrelevant, and the items that were once conceptually similar may become very different,” said Preston, who holds a joint faculty appointment in neuroscience.

For example, the researchers report that many Americans may have chosen their preferred presidential candidate many months ago based on political platforms or core issues. But as the election cycle continued, voters were presented with new information, influencing some to change their perspectives on the candidates and, potentially, their votes.

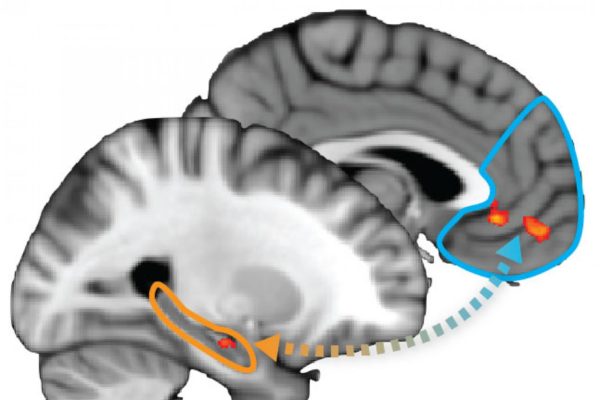

This requires rapid updating of conceptual representations, a process that occurs in the hippocampi (HPC)—two seahorse-shaped areas near the center of the brain responsible for recording experiences, or episodic memory—researchers said. It’s also one of the first areas to suffer damage in Alzheimer’s disease.

According to the study, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) — the front part of the brain that orchestrates thoughts and actions — tunes selective attention to relevant features and compares that information with the existing conceptual knowledge in the HPC, updating the organization of items based on the new relevant features, researchers said.

“Looking forward, our findings place HPC as a central component of cognition — it is the brain’s code builder. I think these findings will motivate future research to consider the more general-purpose function of the hippocampus,” said Mack, who is now an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Toronto. “For example, understanding how we dynamically update conceptual knowledge may be essential to understanding how biases and prejudices are coded into our views of other people.”

These findings add to the growing, though limited, body of literature on the function of the HPC beyond episodic memory by providing direct evidence of its role, in concert with the PFC, in building conceptual knowledge.

“With an understanding of the mechanics of learning, we can develop educational practices and training protocols that optimally engage the brain’s learning circuits to build lasting knowledge,” Mack said.