This story originally appeared in UTLaw magazine.

Five days a week at Webb Middle School in North Austin, a handful of the sixth-, seventh- and eighth-graders spend a class period as prosecutors, defense attorneys, jurors, judges and defendants. These middle-schoolers are trained in their roles, and assisted in parts of the process, by students at the School of Law, who help them frame their arguments, deliberate and raise objections. And while this sounds like most other mock trial programs, there’s one crucial difference between what happens at Webb’s Youth Court and what happens in mock trials at most other schools. Here, the consequences are real, and the stakes can be surprisingly high.

The Youth Court trial held at Webb in March, involved a seventh-grade girl who had been caught skipping an assigned tutoring session and hiding on school grounds with a male student. The charges against her were for lying to her mother and skipping school, and the session began with the bailiff — a boy in a Youth Court T-shirt — swearing in the jury, before all present rose, and the judge entered the classroom.

It was made clear that the purpose of Youth Court was not to determine guilt or innocence, but to decide on the appropriate consequences for the defendant’s actions, and both sets of attorneys made their recommendations. The defendant took the stand and faced cross-examination, and the prosecution read testimony from some of the girl’s other teachers, which they obtained by interviewing those teachers prior to the trial. The jury heard the evidence, left the room to deliberate, and returned a few minutes later, outlining the consequences that the student defendant would face: a letter of apology to her mom, making up the missed tutoring session, participation in a “healthy relationships” program at the school, and the assigning of a School of Law mentor who would help monitor her progress. Case closed, the bell rang and the session ended.

If it all sounds cute — and it was, to some extent — there’s also a serious component here. According to April Scofield, the Webb science teacher who oversees the school’s participation in Youth Court, the girl in question could have faced much harsher consequences if it hadn’t been for the program.

“By the time we get them, they’ve had repeat offenses, and what we’re trying to do is keep them out of the Alternative Learning Center,” a disciplinary institution for students who have been removed from their regular school.

At its most basic level, Youth Court is meant to address the school-to-prison pipeline, the growing national trend where children are removed from classrooms or public schools and set on a path leading into the criminal justice system. With the rise of zero-tolerance policies on campuses, the turning over of classroom discipline to police, and the widespread practice of issuing Class C misdemeanor tickets inside the school walls for behavior that wouldn’t be criminal in other aspects of life, finding new ways to enforce disciplinary infractions is a topic of great importance to a number of educators — and to School of Law students and faculty with experience in the education system.

But what’s most critical to know about Youth Court is that even in its first year, it appears to be making a positive impact.

Youth Court came to the School of Law last year, under the direction of Professors Sarah Buel and Norma Cantu, who had been teaching a class on education policy. Buel moved on to Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law as clinical professor and faculty director of the Diane Halle Center for Family Justice, and Professor Tina Fernandez stepped in as faculty adviser for Youth Court.

“In the class, law students read about the school-to-prison pipeline,” Fernandez said, “and they learned about youth courts, which have been used as a diversion model in high schools. The students, and Professor Buel, got very excited about it. They thought starting it in middle school would be a good idea, because that’s where kids really start to get on the wrong track.”

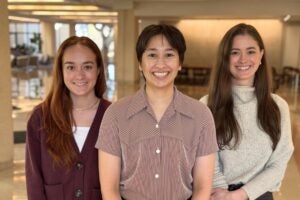

The current program is overseen by Fernandez, who directs the School of Law’s Pro Bono Program out of the William Wayne Justice Center for Public Interest Law, as well as students Meg Clifford, ’12, and Christine Nishimura, ’12. All three women are former educators who’ve worked with Teach For America, and they said that the perspective they gained in the classroom helped them immediately understand the importance of the program.

“The program is essentially a continuation of Teach For America’s mission, which is that, no matter what avenue the alumni may choose or what industry you go into, you remain an advocate for low income communities and an advocate for the education system,” Clifford explains. “In Austin, the school-to-prison pipeline is a thriving, real thing.”

Countering that pipeline is written into Youth Court’s stated goals, and while all of the evidence regarding its success is currently anecdotal, it’s nonetheless compelling.

“There’s one student that we heard about who came through Youth Court, who they were having some real issues with,” Fernandez recalled, “And the vice principal told us that he’s had zero referrals since going through the program. The teachers comment on the fact that he’s done a better job in school and, in fact, he got recognized at a student assembly as the ‘student professional of the month.’ When he was on stage, he said that he had been waiting for that moment his whole life.”

So what is it that makes the Youth Court so effective at helping turn around students who are at risk of being suspended, sent to Alternative Learning Centers, or worse? April Scofield, faculty adviser of the program at Webb, has some ideas. Scofield, who’s in the midst of a master’s program in mediation, attributes the program’s successes to that most powerful of pre-teen forces: peer pressure.

“We’ve actually had students that have said, ‘I don’t want to go in there! Those are my friends!’ For this population,” Scofield explained, “That social aspect is important. They don’t want to be talked about. And when you get sent to Youth Court, your stuff is put out there. They care more about what their friends think than what adults think.”

There’s another important aspect to Youth Court, as well. Fernandez said that the Youth Court system helps change the students’ relationship with authority.

“There’s something to be said about the model in which they’re being adjudicated by peers. It’s another child, one of their peers, really calling them out publicly. Sometimes one of the lawyers will turn to the defendant and say, ‘Why did you say that? What else could you have done?’ And from our preliminary data, you can really see that there is at least some short term self-reflection.”

For the students involved — both the School of Law students and the Webb Middle School students — there are benefits to being involved in Youth Court that go well beyond the actual trials they hold. For the middle-schoolers, it gives them an opportunity to form a relationship with adults who aren’t teachers.

“For a lot of our kids, adults are the enemy, because so many adults have abandoned them, or have not done anything for them,” Scofield said. But the law students occupy a different role. “Slowly, as they start to see the same adult taking interest in them repeatedly, they really open up. I have students come up to me asking for specific law students. There’s a connection, and a bond, that’s happening. It excites them to see adults who aren’t teachers, who don’t have to worry about standardized testing.”

Law student Meg Clifford sees another benefit in helping prepare middle-schoolers for Youth Court, as opposed to mock trial at the School of Law.

“You have to be able to explain things so that a group of middle school kids can understand it. And if you can explain it to a thirteen-year-old, you can explain it to anyone,” she said. “So when considering your average juror in court, if you’re having a complicated legal issue, it helps you remember: ‘I have to break this down enough so that someone else understands what I’m talking about.’ It helps them understand how to question people, and get people to think to that next level, especially when it comes to trial skills. It’s really beneficial to law students. There’s no better way of learning than having to teach.”

Sandra, a seventh-grader, lights up when talking about what she’s gained from Youth Court.

“It’s fun! I really like it. If I ever want to be a lawyer, I have a head start to it.” She paused for a moment, then added. “I probably will be a lawyer in the future.”