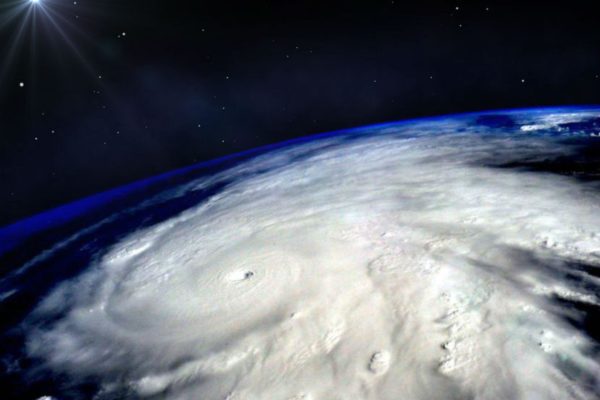

Having grown up in Puerto Rico, I’m more familiar with hurricane season than I’d like to be. Every year, we would brace ourselves for what might be. The entire island would go on alert, and emergency plans would be put into effect at the first sign of an approaching storm.

I know the importance of emergency preparedness firsthand, and I agree that individuals and families must have safety plans in place before a storm makes landfall. But as a public health scholar, I can tell you that real preparedness — the kind that not only saves lives but also preserves livelihoods — is something that’s built into our cities, settlements, roads and infrastructure. And we are woefully unprepared for this year’s hurricane season, which again is predicted to be above average.

In Texas, demographers expect the state’s population to double by 2050. To accommodate that growth, existing cities will be forced to increase density in their urban cores, spread out, or a combination of both. Whatever we choose, we must plan for cities that are better prepared to manage storms, for example, by preserving and designing into new developments permeable surfaces that absorb excess water and prevent flooding.

For years, too many Texas cities had unchecked growth, lack of planning, and real estate development interests that have put a burden on existing infrastructure without helping support the needed infrastructure upgrades that population growth required.

Similarly, smaller suburban cities in Teas are growing into bigger cities to accommodate rapid population growth, and they will need to boost their infrastructure to provide public services — water, energy, waste management, emergency services — to even more people. Decisions now on the design of new neighborhoods, their location and the types of public services available will have a significant impact on the public’s health for years to come, both during dry times and in the event of heavy rains.

We have a choice on how we allocate resources for public infrastructure. We can continue to maintain niches of well-resourced neighborhoods that contrast with poorly resourced communities, or we can be equitable in the way we build, develop and ensure weather extreme preparedness. This matters because we all carry the financial burden of postdisaster recovery. Recovery is a much harder journey when you already start at a disadvantage. It is also at the end much more expensive for everyone, not just for the “have nots.”

Are we, as a country, purposefully ignoring this reality? Maybe. I think that is a function of “if it ain’t broken, why fix it?”— which is shortsighted. We take that approach to individual health more often than not: avoiding that visit to the doctor until the symptoms are too obvious to ignore. In population health, we do not have the luxury to wait until it breaks to fix it. We must invest today to prevent the burden on health tomorrow. Furthermore, because population health is not about the mass delivery of clinical care, it is about all of the things in our lives that shape our access to the things that help us be healthy.

We all have a role to play. It will take all hands to be truly prepared. For example, the engineers, architects, planners, developers and elected officials who influence the shape of our cities can set and abide by design standards that maximize resiliency. The businesses, corporations and industries that put demands on public infrastructure and that incidentally drive much of the population growth and where it happens can contribute to community benefit funds to offset the cost of improved infrastructure upgrades. The social, education and human development sectors that contribute to knitting the social fabric of cities can set the expectation of how public investments are done in an equitable manner.

As we approach the first anniversary of an unprecedented and costly hurricane season, with 17 named storms and 3 hurricanes touching U.S. soil, we must build preparedness into everything we do, and we must do it together. Extreme weather events, from droughts to heat waves to floods from hurricanes, will become more frequent and more intense. The health and well-being of all of us are at stake.

Lourdes Rodriguez is an associate professor of population health and the director of place-based initiatives in the Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin.

A version of this op-ed appeared in the Houston Chronicle, Austin American Statesman and the Waco Tribune Herald.

To view more op-eds from Texas Perspectives, click here.

Like us on Facebook.