AUSTIN, Texas — New evidence in Belize shows the ancient Maya responded to population and environmental pressures by creating massive agricultural features in wetlands, potentially increasing atmospheric CO2 and methane through burn events and farming, according to geographical research at The University of Texas at Austin published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

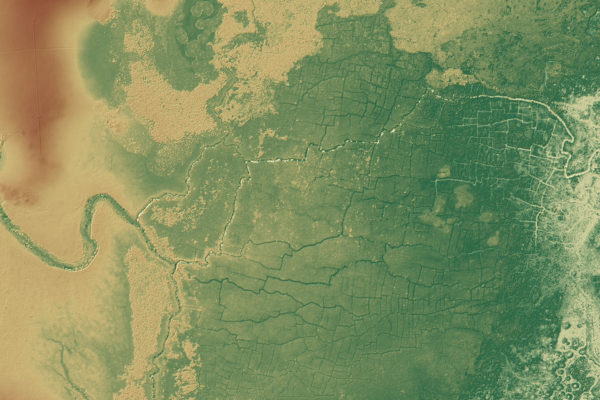

Prior research proposed that the Maya’s advanced urban and rural infrastructure altered ecosystems within globally important tropical forests. But in the first study to combine airborne lidar (light detection and ranging) imagery with excavation and dating evidence in wetlands, researchers found the Birds of Paradise wetland field complex to be five times larger than previously discovered and found another, even larger, wetland field complex in Belize.

Altogether, the study shows the Maya had “earlier, more intensive and more wide-ranging anthropogenic impacts” on globally important tropical forests than previously known, adding to the evidence for an early and more extensive Anthropocene — the period when human activity began to greatly affect Earth’s environment.

“We now are beginning to understand the full human imprint of the Anthropocene in tropical forests,” said Tim Beach, the study’s lead author, who holds the C.B. Smith, Sr. Centennial Chair. “These large and complex wetland networks may have changed climate long before industrialization, and these may be the answer to the long-standing question of how a great rainforest civilization fed itself.”

The team of faculty members and graduate students acquired 250 square kilometers of high precision laser imagery to map the ground beneath swamp-forest canopy, unveiling the expansive ancient wetland field and canal systems in Belize that the Maya depended on for farming and trade through periods of population shifts, rising sea levels and drought.

Evidence showed that the Maya faced environmental pressures, including rising sea levels in the Preclassic and Classic periods — 3,000 to 1,000 years ago — and droughts during the Late/Terminal Classic and Early Postclassic periods — 1,200 to 900 years ago. The Maya responded to such pressures by converting forests to wetland field complexes and digging canals to manage water quality and quantity.

“These perennial wetlands were very attractive during the severe Maya droughts, but the Maya also had to be careful with water quality to maintain productivity and human health,” said Sheryl Luzzadder-Beach, the study’s co-author, who holds the Raymond Dickson Centennial Professorship at UT Austin.

Similarly, the researchers posit the Maya responded to large population shifts and changing demands for food production during the Late Preclassic to the Early Postclassic — about 1,800 to 1,000 years ago — by expanding their network of fields and canals in areas accessible by canoe to the broader Maya world. Within the fields, the researchers uncovered evidence of multiple ancient food species, such as maize, as well as animal shells and bones, indicating widespread protein harvesting.

The researchers hypothesized that expanding the wetland complexes added atmospheric CO2, through burning events; and methane, through the creation of wetland farming. Indeed, the largest premodern increase of methane, from 2,000 to 1,000 years ago, coincides with the rise of Maya wetland networks, as well as those in South America and China.

“Even these small changes may have warmed the planet, which provides a sobering perspective for the order of magnitude greater changes over the last century that are accelerating into the future,” Beach said.

The researchers hypothesize the Maya wetland footprint could be even larger and undiscernible due to modern plowing, aggradation and draining. Additional research on the region and its surrounding areas is already revealing the extent of wetland networks and how the Maya used them, painting a bigger picture of the Maya’s possible global role in the Early Anthropocene.

“Understanding agricultural subsistence is vital for understanding past complex societies and how they affected the world we live in today,” Beach said. “Our findings add to the evidence for early and extensive human impacts on the global tropics, and we hypothesize the increase of atmospheric carbon dioxide and methane from burning, preparing and maintaining these field systems contributed to the Early Anthropocene.”