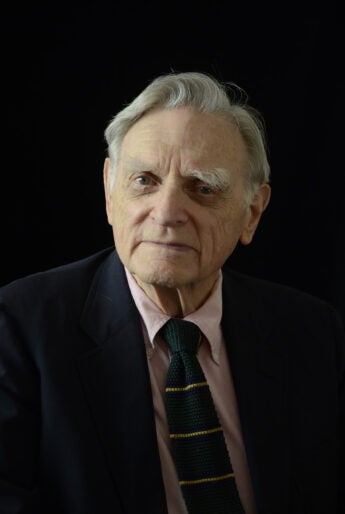

The Nobel Foundation honored University of Texas engineering professor John Goodenough, 97, with the 2019 Nobel Prize in chemistry last fall.

Goodenough, along with researchers Michael Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino, was recognized for contributions to the development of lithium-ion batteries, which power laptops, smartphones and other electronic devices. But those who work with Goodenough say he should be acknowledged not only for his scientific strides but also for his kindness.

“He’s passionate about science, and he cares about humanity,” says Arumugam Manthiram, a mechanical engineering professor at UT. “He’s very keen on doing something good for society in the energy area.”

Manthiram has known Goodenough for 34 years, since joining his lab at Oxford University for postdoctoral research. Just a year later, in 1986, Goodenough moved to Austin to work at UT and persuaded Manthiram to come with him so they could continue their research.

Five years later, Manthiram finished his fellowship and considered a job in New Jersey. But Goodenough urged him to instead become a professor at UT. Manthiram decided to stay and was offered a faculty position.

“He had that intuition about me — what kind of person I am, where I can show my potential — and that changed my life,” Manthiram says. “This is the only place I have stayed in the U.S., no other city, no other university. I enjoy what I do. That chance has transformed my life and my family’s life.”

Today, Manthiram’s office is two doors down the hall from Goodenough’s. The colleagues have collaborated on a project for the U. S. Department of Energy, working to develop materials for next-generation batteries.

Early on, Goodenough taught him much about physics and different approaches to problems, Manthiram says. But he has also become a father figure to him over the years.

“The people who have worked with him, including me, are like his kids,” Manthiram says.

He’s an inspiration to many, including myself, and he’s a role model for everybody.

Hadi Khani, too, considers Goodenough to be a part of his family. The research associate and his wife, postdoctoral fellow Isal Kalami, have worked as researchers in his lab since 2018.

“Dr. Goodenough is brilliant — not just scientifically,” Khani says. “He’s a very, very nice person. He’s kind to everyone.”

For almost a year, Khani says, he drove Goodenough to and from campus each day.

“Whenever he’s at school, I always give him the report of my experiments,” he says. “We chat a lot about science. We also chat a lot about other things together, like philosophy — especially when we are driving. He’s my mentor in both science and life. He’s my good model.”

Khani and Kalami, who have lunch with Goodenough every Saturday, say they don’t plan on moving on from the lab anytime soon.

“I’m not going to leave him here,” Khani says. “I see him every day. I’m going to stay with him as long as I’m alive.”

Nicholas Grundish started working in Goodenough’s lab as an undergraduate mechanical engineering major.

“I had no idea who Goodenough was,” Grundish says. “I knew he was associated with the lithium-ion battery, but in my head it just didn’t click how important that was. I just sent him an email, and he said, ‘Come by my office.’ That was back when he checked his emails.”

Now, five years later, Grundish is working toward a doctorate in materials science and engineering. At a recent conference, he met someone who worked with Goodenough as a graduate student in 1994 — the same year Grundish was born.

Goodenough is “such a kind-hearted and brilliant person,” Grundish says. “You really don’t see that combination much anymore. It’s almost like he sees the world from a different point of view than everybody else. I’m really happy that I got to be a part of that. I got a glimpse of it.”

Manthiram, too, says it has been a unique privilege to have worked with Goodenough.

“I’m lucky to have that opportunity,” he says. “He’s an inspiration to many, including myself, and he’s a role model for everybody.”

The discoveries made in Goodenough’s lab “cut across all parts of our life,” Manthiram says. “The research is critical in everything we do. He worked all his life on materials and put physics and chemistry towards engineering obligations. That’s his legacy.”

HIGHLIGHTS FROM JOHN GOODENOUGH’S CAREER

1944: Earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics at Yale University.

1952: Earned a doctorate in physics at the University of Chicago. Joins team conducting research on advancement of random-access memory (RAM) at MIT Lincoln Laboratory. Stays until 1976.

1976: Became head of Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory at Oxford University, where lithium-ion battery discoveries are made.

1986: Joined the Cockrell School of Engineering at UT and continues material science research. He holds the Virginia H. Cockrell Centennial Chair in Engineering.

2013: President Barack Obama presents him the National Medal of Science.

2019: He wins the Nobel Prize, the oldest person to have ever won.