Earlier this year, a historic cold snap left millions of Texans without heat and electricity. In the face of increasing climatic anomalies and future natural disasters of this scale, Texans need to be well equipped to handle these situations in order to better protect industries, infrastructure and, most importantly, one another.

Today, the Near Surface Observatory (NSO), a scientific group under the Bureau of Economic Geology at The University of Texas at Austin, is helping to do just that.

The NSO group focuses its impact on near-surface environments, or what Director Jeffery Paine dubs “critical life-supporting zones on Earth.”

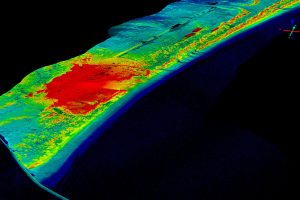

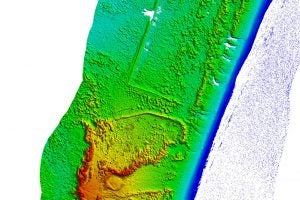

NSO uses airborne lidar technology to create detailed geological mapping in diverse environments. Lidar (light detection and ranging) is essentially laser imaging from above, and it uses specialized instruments on drones or planes that emit light toward the ground. The instruments then sense when and how the light bounces back to determine precise measurements of distance.

Using airborne lidar, NSO routinely surveys Texas lands and updates the state with important geological evolution data. It is crucial that the state always has access to the latest information and mappings, so it can more accurately predict weather patterns, assess infrastructure development and planning, and monitor ecosystems, such as wetlands and bodies of water, and soils for agriculture.

But perhaps the most crucial function of lidar is to better prepare the state for natural disasters or climate anomalies, which have become more common over the years.

In other words, “NSO instruments provide crucial information on the location, extent, susceptibility and severity of these hazards, which allows governments, businesses and individuals to take steps to mitigate the impact of these hazards,” Paine says.

NSO scientists also use lidar after disasters to provide information about damage and predictions for recovery.

After Hurricane Harvey in 2017, NSO researchers worked around the clock to rapidly acquire lidar data and imagery. The team flew the aircraft during the day and handed the acquired data over for processing that night, making critical information available to emergency responders by the very next day.

This data was used for a variety of purposes, including assessing storm impacts on beach and dune systems, identifying debris and infrastructure wreckage, and even helping establish a recovery baseline.

Ultimately, lidar is a powerful tool with a variety of uses including disaster preparation and relief. NSO’s work provides first responders, governmental agencies and researchers with rapidly accessible and trusted data to make important decisions for Texas.

As for the future, “Many challenges face Texas as its population continues to grow,” Paine says. “Just focusing on the coast, for example, prospects for increasing rates of relative sea-level rise threaten our extensive coastal lands where population and infrastructure is also concentrated, making frequent monitoring of those lands today a necessity.”