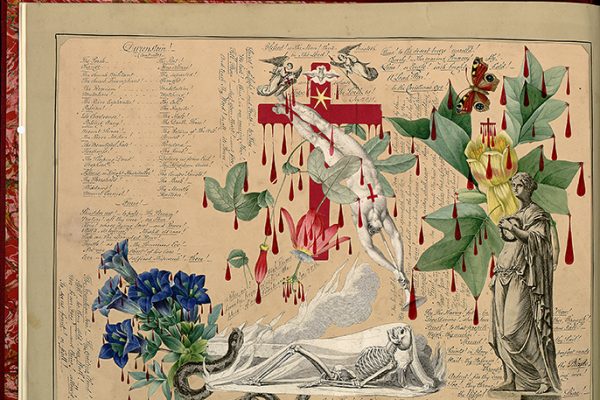

The book’s inscription,in precise, delicate script, is innocuous: “To Amy Lester Garland — A legacy left in his lifetime for her future examination by her affectionate father.” John Bingley Garland wrote this message to his daughter on Sept. 1, 1854, shortly before she married. But open this Victorian decoupaged scrapbook and you won’t find your typical wedding present. The richly illustrated pages feature natural and religious motifs — snakes, flowers, birds, saints, biblical scenes, crusaders, an Egyptian sarcophagus.

And each image is dripping in blood-red India ink.

The “Blood Book,” as it has come to be called, eventually fell into the hands of Evelyn Waugh, the English writer known for such works as “Brideshead Revisited” and “Decline and Fall” and an eager collector of Victoriana. It’s now housed at the Harry Ransom Center, along with the rest of the author’s manuscripts and library. Thanks to the center’s rich digital presence, you can view every page of the “Blood Book” in all its colorful glory.

But in a collection as vast as the Ransom Center’s, how does someone not working on a research project know where to begin to find such treasures? With visitors unable to come to the center during the COVD-19 pandemic, staff members wanted to find a way to keep in touch with the public.

“We’ve just been looking for any possible way that we can engage people during this time, and a lot of that is obviously online,” says Elizabeth Page, head of communications and marketing for the Ransom Center.

Enter “Ransom in a Minute,” a social media project launched last spring by communications and marketing manager Randi Ragsdale.

“We were shut down to the public, and our only way to engage folks were with what we had online,” Ragsdale says, “And I knew we had these really cool collections that covered a wide range, from photography to art, to manuscripts, to performing arts.”

Ragsdale says she recognized that many people, stuck at home and nervous about the state of the world, might not want to devote the time to reading a long blog post. But she might be able to get their attention with highly visual, enticing social media content.

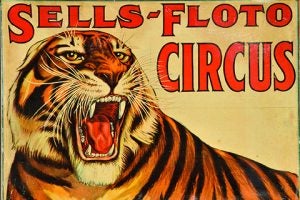

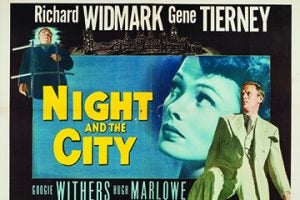

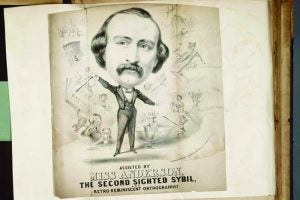

The “Ransom in a Minute” videos — more like online photo essays — showcase a variety of hidden gems and old favorites from the center’s collections. In just 60 seconds, from your computer or phone, you can get an up-close look at the Gutenberg Bible — arguably the Ransom’s most well-known piece — or see pages from the Harry Houdini scrapbook collection. Revisit the Tennessee Williams classic “The Glass Menagerie,” or get a peek at how Julia Child’s “Mastering the Art of French Cooking” came together.

And if the “Blood Book” got your attention, wait until you see Leigh Hunt’s “Hair Book.”

Hunt, a poet and essayist, collected human hair. His book contains locks that allegedly belonged to George Washington, Napoleon, William Wordsworth, Mary Shelley and other politicians and writers.

“Ransom in a Minute” isn’t meant to represent the entirety of a collection, Ragsdale says. The videos tell interesting stories that give an insider’s view of what can be found.

“What makes our collections I think so fascinating is what’s inside,” Ragsdale says. “An author’s collection isn’t just their papers, right? It’s notes and photographs and scraps of who knows what. And those are the things that tell the story of these people.”

The hope is that visitors, intrigued by the videos, will go further into the Ransom Center website to learn more.

“It’s a big opportunity to just increase awareness about our collections, the types of collections we have, and then give people an opportunity to dive into what we have online no matter where you are,” Ragsdale says.

Ragsdale and Page say the videos have proved to have widespread appeal, from Instagram fans to longtime researchers.

“In this case, we were really trying to connect with the online audiences and give people something to do at home,” Page says. “But I found that our advisory council members, volunteers, everybody is tuning into that. Even people who might have more of a research background in one area, they might not know that we have something in another area.”

The papers, photographs and ephemera you can see online are only a fraction of the Ransom Center’s holdings. Digitizing collections requires time and, often, grant money. But quarantine closures have helped show how important that work is to the preservation of cultural heritage.

“Now everybody really sees the value of having your collections digitized and making sure that you have content that is available online,” Ragsdale says. “I think we’re going to see a lot more of these types of things going on in the future.”

Digital collections also are more accessible to the public and far-flung researchers.

“That’s the whole point behind digitizing collections,” Page says. “We might have 3,000 researchers who come and visit within a given a year. But, if we can share that collection online, there is so much more potential for that material to be used and for people to learn from it.”

The Ransom Center’s Visit From Home page includes links to the “Ransom in a Minute” series and other videos from the center, online exhibits and links to highlights from the digital collections, including a group of movie posters from the 1940s to 1970s, early works by Charlotte Brontë, collections related to John Keats, Lewis Carroll and Edgar Allan Poe, the Gabriel García Márquez collection and much more.