AUSTIN, Texas — Using laser mapping data, researchers from The University of Texas at Austin and other national and international institutions have discovered 478 ancient ceremonial centers in southern Mexico. Most of the sites probably date to 1100-400 B.C., several centuries before the Classic Age (A.D. 250-950) of Maya civilization.

The findings, published in Nature Human Behavior, further scholars’ understanding of the origins of Mesoamerican civilizations, particularly about the relationship between Olmec and Maya cultures. The newly found sites demonstrate the influence of Olmec architectural innovations on Maya centers of the Classic Age and broaden our knowledge of how the Olmec civilization transformed their environment through agriculture.

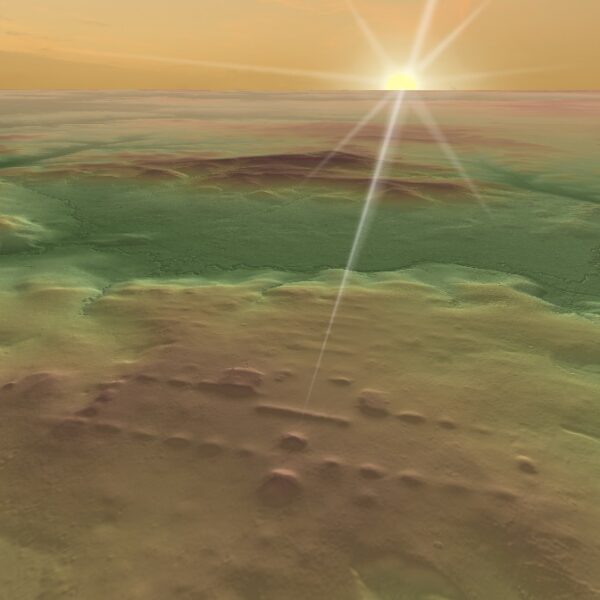

Lidar (Light Detection and Ranging) is a technology that can penetrate vegetation to map three-dimensional forms of the ground and archaeological sites. This study used publicly available lidar data obtained by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI), a Mexican governmental organization. It covered an area of 85,000 square kilometers, equivalent to the island of Ireland, representing the largest archaeological lidar study of Mesoamerica.

The hundreds of newly identified rectangular and square complexes show highly standardized formats and were probably the earliest material expressions of basic concepts of Mesoamerican calendars and a number system.

“These cultural centers showed remarkable regularity in sizes and orientation along cardinal directions and were a landscape manifestation of the essential concepts of the Maya calendars and number system,” said study co-author Timothy Beach, a professor in the Department of Geography and the Environment at UT Austin. “Mesoamerican belief and knowledge systems are apparent in the landscapes they terraformed.”

The largest of the complexes and the largest and earliest Maya platform, Aguada Fénix, was previously reported in Nature. The present study shows that similar ceremonial complexes were built across a broad area, including in the Olmec region and the western Maya lowlands. The study suggests that the standardized complexes in this area declined after 400 B.C., but some of their elements were adopted by later Maya centers, providing an important basis for Maya civilization.

Many of the newly discovered sites lie in the coastal, tropical forest lowlands in the Mexican states of Tabasco, Veracruz, Campeche and Yucatán, and they demonstrate the early agricultural activity of Mesoamerican civilizations.

“The study shows widespread, intensive wetland adaptions into agroecosystems along high population sites in the Mesoamerican Classic Period staring around 1,500 years ago,” Beach said. “The juxtaposition of the Mesoamerican centers and intensive agriculture shows the connection of Mesoamerican cultures with tropical swamps and their magnificent ecosystem services.”

The study was done in collaboration with the University of Arizona, Tucson; the University of Houston; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City; Middle Usumacinta Archaeological Project, Balancán, Mexico; the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa-Ancón, Panama; INEGI, Aguascalientes, Mexico; Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Veracruz, Mexico; and Universidad para el Bienestar “Benito Juárez García,” Papantla de Olarte, Veracruz, Mexico.

The Alphawood Foundation and National Science Foundation funded the project.