If the restoration of the Tower at The University of Texas at Austin were not important for any other reason, it would be important because we simply don’t make buildings like this anymore.

If you’ve driven around Texas much, you’ve no doubt been struck by the fact that no matter how small a town is, if it is a county seat, it probably has a historic courthouse, and that building is likely to be the most impressive building in that county, especially if it was built between 1870 and 1910. On the squares of Waxahachie, Lockhart, Mason and dozens of other towns, they sit like gingerbread castles surrounded by bank branches, hardware stores and barbecue joints.

I love these buildings not merely because they are old, but, like our Tower, because they were built during an age when aesthetics really mattered, especially when it came to public buildings. It was an age when people took enormous pride in the details — whether those details were the construction materials, the architecture or the symbolism and messages embedded in the structure.

Think of any central administrative building or library erected on an American campus during the past 60 years. (We need not name names.) These might have all the amenities and none of the functional quirks of our Main Building and Tower. Designed with modern HVAC from the get-go, they would be more energy efficient, and topping out at three or four stories, they would be cheaper to build and maintain.

But they aren’t like this building.

They don’t possess the monumental scale or the variety of materials. They don’t evince the thoughtfulness or have the character. The word that best describes buildings of the past half century, even the nice, expensive ones, is “non-descript.”

Our mega-society, with its sprawling office parks, gigantic distribution centers, big-box stores and apartment complexes, takes the path of least resistance when it comes to building. Aesthetics, if considered at all, are the final step — a strip of cornice grudgingly slapped along the top-front edge of an otherwise featureless box.

Even the nicest university buildings constructed today have an aesthetic driven by economics and utility and technology. They are thoroughly modern, of course, and feel corporate. But then, in the early and middle of the past century, banks, train stations and movie theaters — all creatures of commerce — were majestic too, so the difference between then and now must be something deeper still. A century ago, even a post office was a source of immense civic pride, with great thought put into virtually every detail.

UT’s Tower was not built for efficiency: To get to my office on the third floor, one must take the Tower elevator to 8. To get back to the ground floor, you press “1,” which is not the first floor. Explaining this to visitors can feel like a Vaudeville routine or a scene by Kafka. Bugs like this were mainly the result of it being piecemealed, with major sections being conceived and built several years apart.

Nor was it built as cheaply as possible. Its $2.8 million price tag translates to about $65 million today, but a Tower was never the cheapest design. English professor J. Frank Dobie famously complained that the Tower should have been laid on its side; after all, he said the one thing we have lots of in Texas is land. What an irony that the 1972 building named for him, Dobie Center, is exactly as tall as the Tower he criticized: 307 feet.

Rather, it was meant to make a statement. The grandeur of the Tower’s design pushed UT to greatness, and by restoring the Tower, the University hopes to rekindle that same spirit.

The grandeur of the Tower's design pushed UT to greatness, and by restoring the Tower, the University hopes to rekindle that same spirit.

This building will never be called non-descript, or cookie cutter, or cheapest available. The Tower oozes with character because of its style, which blends neoclassical themes such as pillars and arches (Beaux-Arts, to be specific), regional references such as Spanish tiles, and, on the Tower itself, Art Deco lines, which connect it to the era of its creation.

What’s more, every part of the Tower presumes its permanence. University leaders had learned their lesson with Old Main, which was beautiful and beloved but poorly built. After only 40 years, large parts of it were deemed unsafe for occupation. The new Main Building was going to be built, and built for the ages.

Consider its materials: Its exterior walls were constructed of Indiana limestone, harder and more durable than local limestone. Its red roof tiles were made in Spain, and the marble for its grand stairway, steps and floors was mined in West Texas, Tennessee, Missouri, New York and Vermont. We brought bits and pieces of the wider world here to make it as good as it could be.

But we were also blending those with local material. Its doorways were framed in a locally quarried limestone called Austin shell stone. And, in a nod to frugality, bricks from Old Main, made in Austin, were reused for some inner walls.

The Main Building’s interior was not Sheetrock and paneling, but was finished with terrazzo, tile, wood, stone, terra cotta, cement, marble, plaster, steel and wrought iron. Again, for the ages.

Architects custom-designed furniture for the Main Building’s libraries, including tables, chairs, desks, card catalogs, bookcases, benches, lockers and book trucks.

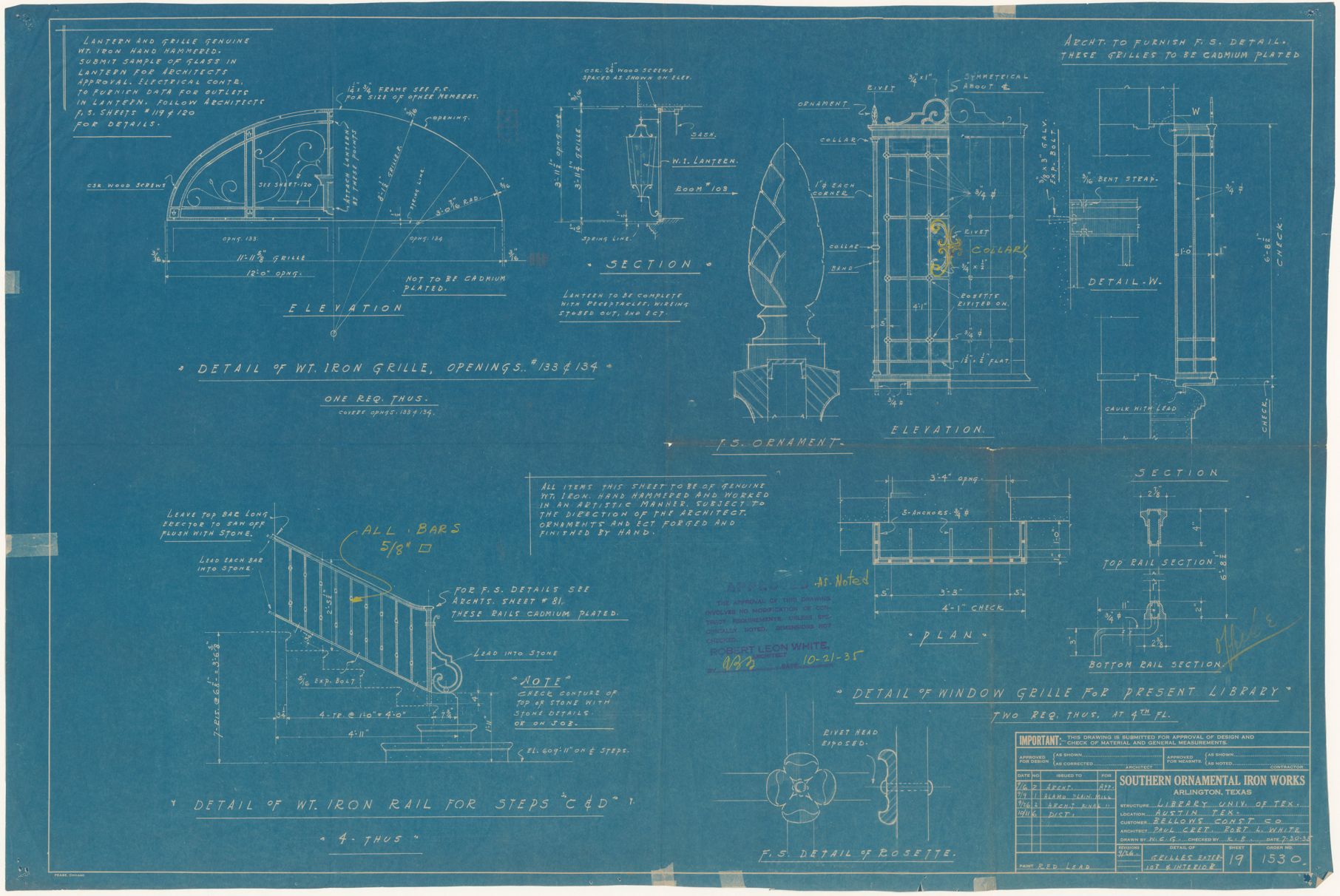

They specified the kind of glass in the windows. Copper screens. Metal-frame louvers. Caulking and grout. Cadmium-plated grilles. They designed wall sconces and handrails and the finials on the bannisters. The blueprints for these many custom objects, which of course were subcontracted, contain notes such as: “All objects this sheet to be of genuine wt. iron, hand hammered and worked in an artistic manner. Subject to the direction of the architect, ornaments and etc. to be forged and finished by hand.”

Other notes stipulate tersely: “Must be approved by architect.”

Lastly, consider the thought that went into the inscriptions and seals that adorn so much of the Main Building and testify to the intellectual oeuvre of campus at that time. William Battle, beloved professor of Greek and chair of the Faculty Building Committee for 28 years, coordinated and had the final say in virtually all these details. (He is the namesake of Battle Hall, the Battle Oaks and the Battle Casts, which now reside in UT’s Blanton Museum of Art. In a faculty coup for the ages, he also claimed the elegant high-ceilinged, wood-paneled 27th floor of the Tower for the Greek Department, which included his own office. Its bookshelves held Battle’s personal library of 10,000 volumes, which donated to UT.)

- Wrapping around north side of the building and into its two courtyards are gilded Egyptian hieroglyphics and letters from the Phoenician, Hebrew, Greek and Latin alphabets. The 113 cast-iron panels were made at a foundry in Dallas. Battle commissioned and approved them, and they were brought to Austin on a flatbed truck weeks before then-President H.Y. Benedict was informed. In a 2010 article about the letters, now-Professor Emeritus John Huehnergard said “The letters represent the history of the alphabet and, by symbolic extension, the history of learning. A fitting decoration for an edifice that was built as a library and as a symbol of learning and knowledge at the University.”

- Below the eaves of the east and west sides of the building are mounted seals of 12 other universities deemed necessary precursors of UT. Professor Frederick Eby, then the campus authority on the history of higher education, provided Battle a list of 15 candidates, and the two trimmed the list to a dozen: Bologna, Paris, Oxford, Salamanca, Cambridge, Heidelberg, Mexico (the first university in North America, 1553), Edinburgh, Harvard (the first university in what would become the United States, 1636), Virginia (the first public university the United States, 1819), Michigan (which Eby claimed had the greatest influence on state universities), and Vassar (representative of women’s education). Moreover, it was a signal that this was the league we were in.

- As a library, naturally the names of 14 authors adorn the outside of the building, from Aristotle to William Shakespeare to Mark Twain.

- Before the UT System established its own buildings downtown, the Board of Regents met in palatial Room 212, now known as the Lee Jamail Academic Room. The gold-leaf inscriptions on the ceiling of that room depart from the purely literary and philosophical and trend toward the civic, political and economic, in keeping with the regents’ constitutionally derived leadership of the University. The Texas Constitution itself supplies “The Legislature shall establish, organize and provide for the maintenance, support and direction of a University of the First Class.” Another interesting quote comes from Ashbel Smith, first chairman of the Board of Regents, when he said during UT’s 1882 cornerstone-laying ceremony, in an allusion to Moses: “Smite the rocks with the rod of knowledge, and fountains of unstinted wealth will gush forth.” In 1923, an oil rig called Santa Rita No. 1 “came in” on West Texas land the state had set aside to help fund education, spraying oil over a 250-yard area around the well and signaling a new day for the University.

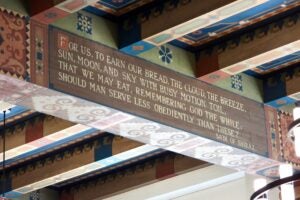

- The quotations used in the Hall of Noble Words, inside what is now the Life Sciences Library, have an interesting origin. In 1933, William Battle sent a letter to select members of the faculty and staff reading: “As a part of the decoration of the ceiling of the east reading room of the new library, the Building Committee contemplates the use of noble and inspiring utterances appropriate to the function of the room as an educational agency. The concrete beams offer long, broad surfaces well adapted for such a purpose … We might, with propriety, call the reading room The Hall of Noble Words … The Committee would be greatly pleased if you would suggest utterances that seem to you appropriate. Perhaps the thoughts expressed may occasionally find lodgment in the minds of users of the reading room.” Among the thinkers quoted are Aristotle, Shakespeare, Roger Bacon, Blaise Pascal, Stephen F. Austin and Mirabeau Lamar. Lines from Sa’di of Shiraz, Alfred Tennyson, Rudyard Kipling and biblical scripture are found on the beams as well, even a passage from “Alice in Wonderland” (prefiguring UT’s acquisition of numerous Lewis Carroll papers in 1969). Architect Paul Cret was enthusiastic about the painted quotations and mused: “Do not be afraid of having the color scheme too high in key at first. It will become subdued with age — like all of us.”

- Finally, there is that most famous inscription, which was chosen to adorn the front of the building. Not content to play second fiddle to the great thinkers of history, Battle originally simply wrote his own inscription: “The records of the past shall give light and courage to them that come after.” Though the committee members may have loved Battle, they did not love his attempt, so they asked math professor John Calhoun to offer an alternative while preserving the spirit of Battle’s idea. Calhoun suggested “Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free,” a quote from Jesus recorded as John 8:32, which gained the necessary buy-in. Calhoun was not promoting religion with the choice, but simply found the quote descriptive of a college student’s use of a library, and it fit the space Cret had reserved for it perfectly. Coincidentally, Calhoun became interim president in 1937, the year the building was completed.

In 1976, irreverent Student Government officers (who had won as the Absurdist ticket on the Arts and Sausages platform, a play on Arts and Sciences) proposed the inscription be changed to “Money talks.” But the snarky, anti-establishment suggestion was unintentionally prophetic.

Money does talk. That is why the Board of Regents committed millions of dollars so that the Tower could once again say: “Here we are. This is our Tower. This is the capitol building of Longhorn Nation. And capitol buildings are for the ages.”

The author thanks alumnus and UT historian Jim Nicar for his extensive research and documentation of the Main Building and Tower details over many years. All photos Avrel Seale/UT Austin

Explore Latest Articles

Feb 20, 2026

Longhorns Level Up at 2026 Academic Esports World Tournament

Feb 20, 2026