“The Main Building of The University of Texas is so large, so important, so complicated, and so full of interest that a detailed description of it seems appropriate.”

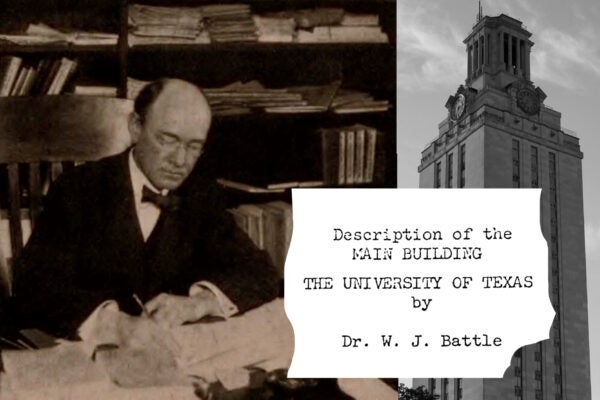

Thus begins an detailed portrait of the emblematic building professor William Battle had such a big hand in creating. In the early 1950s, toward the end of his long life, Battle wrote a document, kept safe in the Briscoe Center for American History, that describes the building he focused so much attention on and atop of which his own office sat, though he does not as much as mention his own role as longtime chair of the Faculty Building Committee or any of his own contributions to its creation.

At times, the document is so detailed it seems to be a catalog of every variety of marble in existence. At other times, it is soaring poetry, expressing the building’s grandeur and beauty in simple truths.

He suggests approaching the building from the South Mall for maximum effect, and after describing the mall, writes:

“… finally, the building itself, a central mass with wings outstretched like friendly arms, and the great Tower rising over all. The sight is beautiful by day; it is even more beautiful by night, for the lighting gives an effect of fairy-land. … The Tower, 307 feet high, is beautiful at all times. By day, its aspect varies with the atmosphere. Now it is brilliant with sunlight, now it is soft gray, now clouds float about it.”

The description is chock-full of interesting facts. For one thing, the Main Building is deeper than it is wide. There’s something about the image most of us carry in our minds of the Main Building and Tower — the postcard image — that makes us think it would be wider than deep. But in fact, while it is 229 feet across, it is 262 feet deep. The Tower itself is just 59 feet square.

He explains that the Main Building sits at the center of the original 40-acre tract set aside by the Congress of the Republic of Texas for a public university. Guadalupe Street to the west is the only street that still defines the boundary of campus, the other three being 24th Street to the north, Speedway to the east (formerly known as Lampasas Street) and 21st Street to the south.

Sitting atop what was once known as College Hill, the base of the Main Building is 55 feet higher than the base of the Capitol, and for many decades this made it the highest building on the Austin skyline, even though the Capitol was slightly taller. Battle writes that during the 1890s, professor Thomas FitzHugh proposed a broad walk around the perimeter of campus. The Peripatos was named after a walk around the Lyceum in Athens, where Aristotle would lecture while walking. UT’s Peripatos, like much else, was funded by Maj. George Littlefield. Tracing a square a quarter mile on each side, it was exactly a mile. So, if you’re walking on a sidewalk inside the square defining the Forty Acres, you’re tracing the old Peripatos.

As we reach the building itself, he writes:

“… a broad Loggia is one of the pleasantest features of the building — a cool, spacious spot, always holding out an invitation to stop and exchange friendly greetings. The steps leading from the Loggia into the building are also of Austin hard shellstone. This stone, quarried near Austin, is almost as hard as granite. It belongs to the Edwards Lower Cretaceous Formation and is full of fossils. Herein will the thoughtful mind see a good illustration of how one age climbs upward over the life of another.”

Around on what he terms “the North Front” (not the back), he writes:

“The North Front is impressive by its happy proportions and its massive simplicity. In the center, separated from the wings by open courts, is the main book-stack of ten levels. … On the east, north, and west faces … are inscribed in large gold-leaf letters the successive alphabets from which are own is derived, five in number: Egyptian, Phoenician, Hebrew, Greek, and Roman.”

Battle then takes us floor by floor (in the Main Building, not the whole Tower), describing the points of interest for the visiting public. Under the heading “Some Things to Notice,” he writes, “Attention is called to the beauty of the floors. The material varies with the purpose of the room. The most used rooms and corridors have rubber tiles in different designs, notably pleasing in color and very comfortable to walk on, when they have not been waxed too much.”

With infectious enthusiasm, Battle calls our attention to the terrazzo floors, the oak floors, and even the linoleum, then to the light fixtures “of great interest,” the walnut and oak woodwork, “notably good” both in its millwork and carving.

On the ground floor was the Reserve Reading Room in the northwest wing, the offices of the registrar in the southeast and the bursar in the southwest. The Newspaper Reading Room in the southwest wing contained more than 16,000 volumes and 5,000 volumes unbound. “In newspapers of the South and of Texas, it has no equal except in the Congressional library at Washington,” he bragged.

He then describes the Grand Stairway:

“From the ground floor south of the main corridor rises to the first and second floors the Grand Stairway, a really beautiful construction. It has double flights of Gray Tennessee marble steps, wrought iron and bronze balustrades, rich walnut grilles, plaster vaulted ceiling with coffers in blue and gold, and walls faced with Magnolia Gray marble from West Texas. The huge windows are framed in French Gray Marble from Vermont; they would be much improved by opaque glass,” he wrote, a subtle dig at the somewhat dingy view into the inaccessible courtyards.

Of the first floor, Battle writes: “The more important first floor rooms in the southwest wing are the offices of the President and the Vice President [singular] of the University, and the Dean, [and] of the Business Manager and Auditor. From the central elevator lobby narrow stairs rise on the east to the mezzanine and the offices of the Dean of Student Life, on the west to the offices of the Dean of Women.”

The longest passage is his description of the second floor, which begins with the elevator lobby and the portrait corridor along the wall to its south, where the Lee Jamail Room is today (Rm. 212). There, he catalogs the portraits of 23 important figures to the University and to the culture of the time including Guy Bryan, Robert E. Lee, Sir Swante Palm, governors Jim Hogg and Oran Roberts (“The Old Alcalde”) and his wife, and other names familiar to us from campus place names: Brackenridge, Benedict, Parlin, Mrs. Rowand Kirby (“lady assistant in the University”), Dean T.U. Taylor, James Clark and his wife, and a painting of Battle himself.

We then move through “shining bronze doors” into what was known as the Regents Room (Rm. 212),

“a large room extending through two stories, intended for formal University functions, now the meeting room of the Board of Regents. This is certainly one of the handsomest rooms in Texas. Above a fine marble wainscot of Tennessee Dark Cedar (base), Phantasia Rose from Tennessee (panels), and Veinless Gray Tennessee (framing), the walls are paneled by balusters of Phantasia Rose and hung with silk damask. The ceiling is tunnel vaulted in plaster with a floral decoration and gold leaf. …. On the wall ends and the curve of the vault in gold letters are utterances dealing with knowledge and education.”

He details each of them, from the aforementioned Benedict and Roberts to the Texas Constitution, Democritus, and Lao Tzu: “To know one’s ignorance is the best part of knowledge.”

Off each end of the Regents Room had been two richly decorated “rooms for leisure reading”: one for men and one for women. But by the time of Battle’s writing, the rooms had been converted to offices. The west one (now a meeting room) was then the Office of the Chancellor, before the UT System had acquired its own buildings in downtown Austin. The room to the east (now the Office of the Provost) housed the assistant to the chancellor. “Both have in niches plaster busts of famous writers, the one to the east Shakespeare, Sophocles, Homer; that to the west Voltaire, [Benjamin] Franklin, [Julius] Caesar.”

Beyond the current provost’s office to the east lay offices of the librarian, secretary of the Board of Regents, vice chancellor and comptroller. On the floor’s southwest wing were the headquarters of the Development Board.

Across the Grand Staircase to the north lay the cavernous space now known as the Life Science Library. This complex of three grandiose rooms was the heart and soul of the building. In Battle’s day the first room one entered was called the Loan and Catalog Room.

“This great room of two stories and height is one of the most striking in the building. The floor, laid with a beautiful pattern of rubber tiles; the bronze light fixtures; the walnut wood-work of the grilles, doors, and ceiling; the marbles of the loan desk and the walls are all worthy of study.”

French Gray marble from Vermont, wainscot of Magnolia Gray from West Texas, St. Genevieve Rose from Missouri, pilasters of pink lepanto from northern New York, and on it goes.

Battle explains that the Loan and Catalog Room is also called the Hall of the Six Coats of Arms. “Texas has made much of the fact that it has lived under six nations. … The six flags of these nations have often been brought together for decorative purposes, but here for the first time have their heraldic arms been so used.” He then gives an exhaustive and scholarly breakdown of each of the shields and their inscriptions with translations.

To the west was what was then called the Business and Social Science Reading Room. He explains it was named the Hall of Texas because of the paintings on its beams, each devoted to a period of Texas culture: Aztec, Indian, Period of Discovery, Spanish conquest, French attempt at colonization, Spanish settlement, Establishment of Mexican independence, American settlement, Texas Revolution, Republic of Texas, Public Life in the First Period of Texas as a State, Private Life in the First Period of Texas as a State, Texas as a State of the Confederacy, Rebuilding Texas, and finally, First Half-Century of The University of Texas. For each side of the eight beams, there are five to seven paintings that he lists. Around the walls were the latest issues of 1,110 periodicals.

To the east sits the Hall of Noble Words, then called the Humanities Reading Room. These beams bear painted quotations. He transcribes all 43 quotations, then explains that the beam supports carry 16 famous printers’ marks from the past four centuries, from Fust and Schoeffer of Mainz to Houghton, Mifflin and Company of New York to Southwest Press of Dallas. And over the hall’s door is “A representation of the top of the central tower of the old Main Building, carved in walnut…”

The third floor leads us to the Latin-American Room on the northwest. “The Latin American room is reminiscent of Spain: the cork floor, the blue and white tiles, the wall and ceiling decorations, the furniture all have their inspiration there. The carved woodwork in walnut is a representation of Garcia’s book-plate the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl and the motto ‘Para Obrar Saber,’ ‘Be sure before you act.’ The catamount [mountain lion] head is modeled after that of a huge specimen killed near Austin,” he writes.

“At the east end of the third floor corridor is the Library School. The main room is done in Elizabethan style because it was originally intended for an English collection. It is a beautiful room, though shorn of much of its charm by the changes made to adapt it to its present function.”

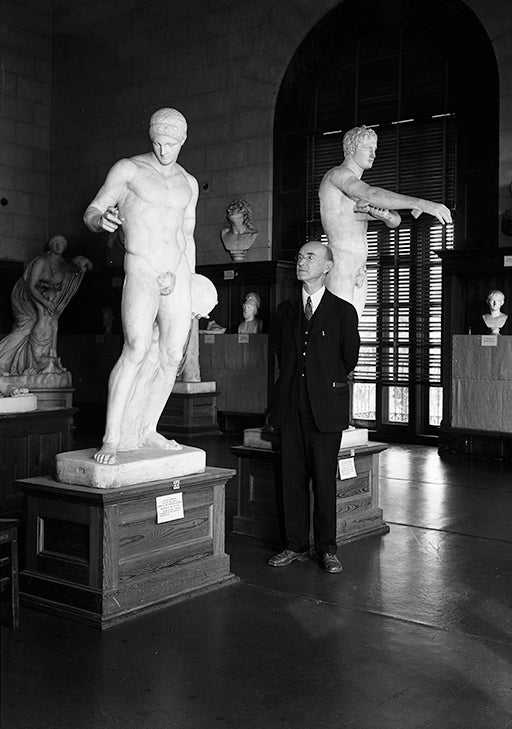

The only public room on the south side of the third floor was the Classical Sculpture Gallery (Rm. 309). “Here and in the lobby and the adjoining corridor are some 50 copies in plaster of famous pieces of ancient sculpture such as the Hermes by Praxiteles, the Aphrodite from Melos, the Victory from Samothrace. The copies are in full size, some being painted so as to reproduce the originals in color as well as in form.” These sculptures, known as the Battle Casts, are now on display in UT’s Blanton Museum of Art and Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports.

During the 1970s, the fourth floor became the Office of the President. But before then, it was the crown jewel of the UT’s library, the Rare Book Collection. “In all the rooms of this floor the decorations and fittings are worthy of their rich contents,” Battle writes. “The north windows command a fine view of the Tower. From the Central Elevator Lobby through a striking doorway of shining bronze we enter the Exhibition Room of the rare book collection, where a special exhibition is nearly always in progress. The walls present a study in green — three shades of marble. … To the South of the Exhibition Room is the Wrenn Room containing the Wrenn Library collected by John Henry Wrenn of Chicago and presented to the University in 1918 by Major George W. Littlefield at a cost of $225,000. … The wood-work is of walnut, the metal-work of wrought iron, the light bowls of alabaster. … The wood ceiling is painted in three series of designs illustrating (1) the development of printing, (2) the history of dress, (3) the arms of famous universities.”

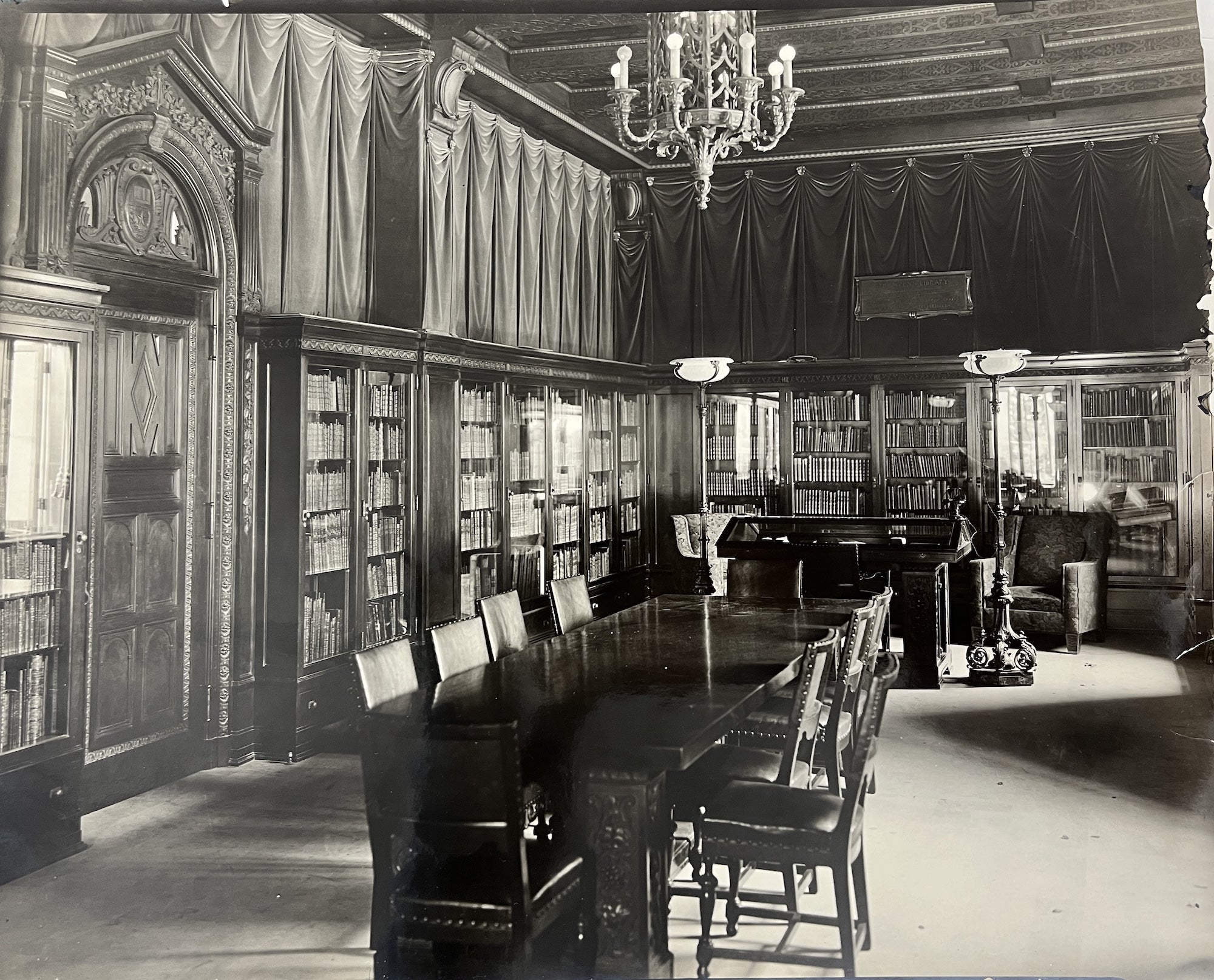

To the east lies the Stark Library, where even the furniture comes from Mrs. Miriam Lutcher Stark’s residence in Orange.

“The Stark Library of some 7,500 volumes is especially rich in books relating to nineteenth century English poets and novelists. In America the Browning Collection is equalled only by that of the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, the Shelley collection only by that of the Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery at San Marino, California. The books visible in the cases are but a part of the Library; the others are kept in a book-stack under the floor.”

The room that now serves as the president’s office itself, then called the Rare Book Study, gets one brief paragraph:

“As the name implies, the room is intended for students and is not open to the public. The wood-work is of oak, the metal-work of aluminum. In this room and in the bookstack below the floor are kept the George A. Aitken collection, rich especially in works of the time of Queen Anne, and other smaller collections. Indeed most of the University’s books, outside the Wrenn and Stark collections that are so valuable as to need special care are kept here.”

Of the roof gardens, Battle writes: “Their fine views, their constant breezes, and their freedom from noise give them a rare charm.”

Since the vast majority of the Tower itself was not open to the public, Battle did not bother to describe its contents except to say that the book-stack had a capacity of 1,725,000 volumes but at his writing contained 430,000. He did say, “Next to the windows around three sides of the book-stack are 210 alcoves or carrels for research students,” and that the Tower “includes an elevator that serves all floors, a book lift to the 27th floor, a book conveyor to the 15th floor, a stairway from bottom to top, and a house telephone on each floor.”

Returning to his earlier description of the Tower, he explains that the Tower’s four clockfaces are more than 12 feet across. He adds:

“… Except for a quarter past eight at night through six in the morning, the clock marks the quarters by the four bells of the Westminster Chime and strikes the hours on a bell weighing three and a half tons. These bells and others, seventeen in all, hang in the square colonnaded belfry that rests on the clock-story and forms the crowning feature of the Tower. The bells are played from a clavier. … To some poetically minded folk the Chime says: Lord, through this hour / Be Thou my guide / For in Thy power / I do confide.”

He writes, “Twin elevators run to the 27th floor whence stairs lead to the Observation Gallery, open to visitors on weekdays from nine to twelve in the morning and in the afternoon except on Wednesday from two to five. The view is magnificent….”

Then, in one paragraph, Battle carefully describes his own perch overlooking the campus he had so influenced for so many decades: “The 27th floor is occupied by the Department of Classical Languages. In the lobby is a small but valuable collection of classical antiquities. Two of the rooms are unusually attractive — the Classical Library and the Library of the Senior Professor of Classical Languages [himself].”