“WOULD LIKE TO HAVE A PROPOSAL FROM YOU ON NOVEMBER TWENTY-EIGHTH COVERING THE INSTALLATION OF AN ELECTRIC CARILLON FOR TOWER OF NEW BUILDING STOP COULD YOU COME TO AUSTIN TO DISCUSS DETAILED REQUIREMENTS FOR SUCH AN INSTALLATION THIS WEEK”

This November 1934 telegram from Robert Leon White, associate architect of UT’s Main Building and Tower, to the RCA Victor Company in Dallas is among the earliest evidence that University of Texas leaders were considering not merely a clock with a bell for its new building, but a carillon. (A carillon is an instrument that plays bells in much the same way an organ plays pipes — with a set of levers pounded with closed fists instead of keys and with foot pedals.)

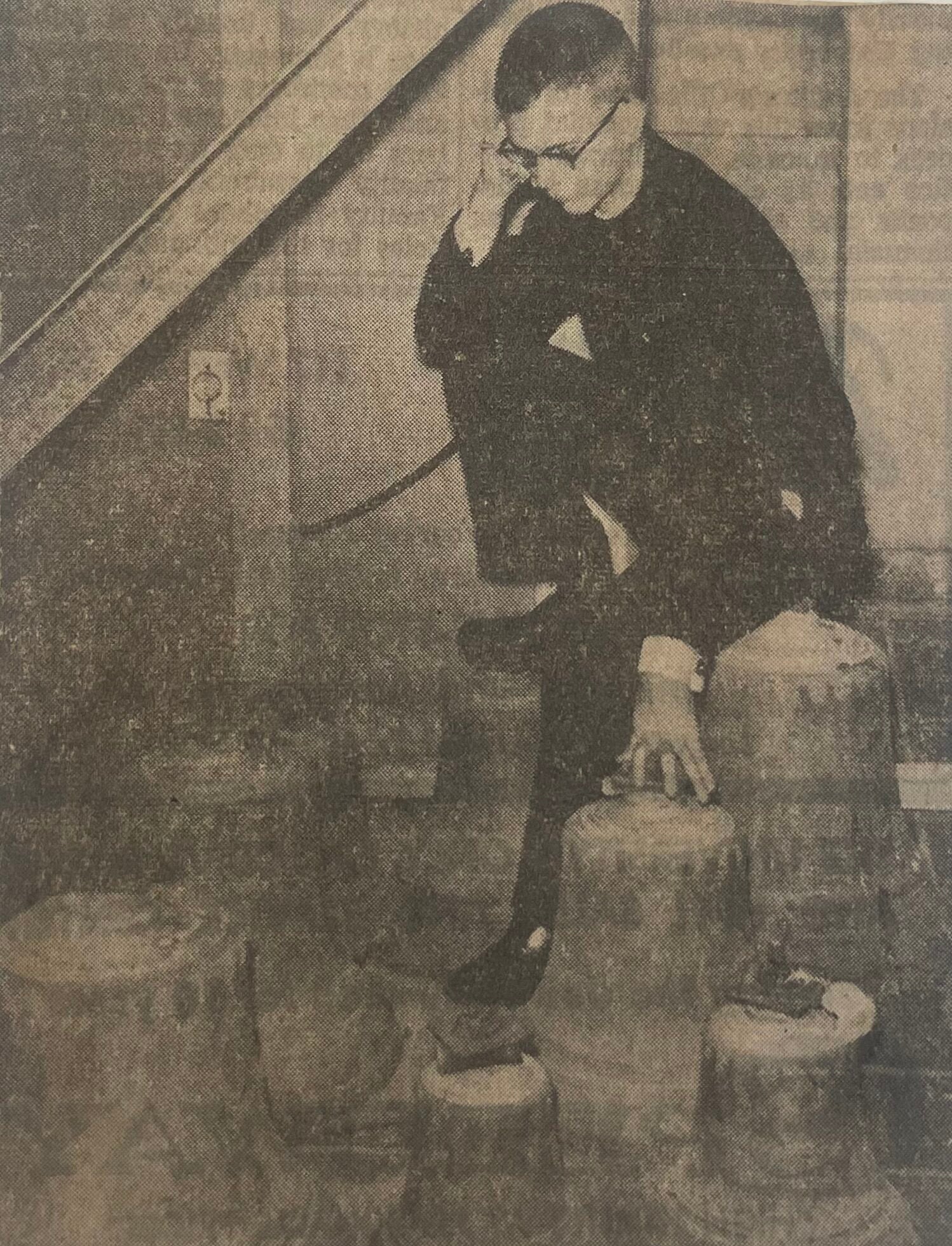

The University had already owned one carillon of sorts. In 1929, Albert Burleson, an 1884 UT law graduate who had served as a congressman and postmaster general, anonymously donated a set of 11 bronze bells to the University, on which very simple tunes could be played. (A true carillon has at least 23 bells forming a chromatic scale.) The generous Burleson’s timing was bad, as they were installed in Old Main just four years before it was razed. The bells then spent nearly 50 years in storage at what is now the J.J. Pickle Research Campus and were returned to the Main Campus in 1981. Since then, “The Burleson Bells” have stood watch over Bass Concert Hall.

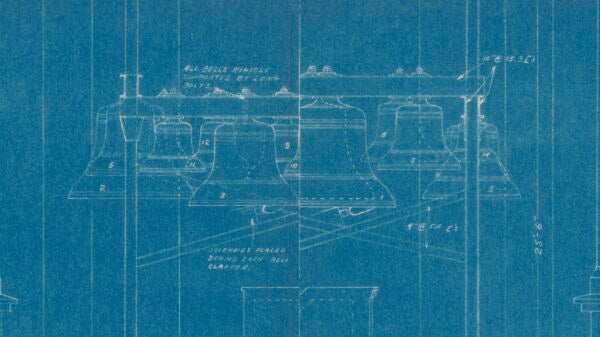

The new Main Building’s belfry would allow for many more bells, but the University could only afford 16 of the copper behemoths. Lutcher Stark, a lumber magnate who chaired the Board of Regents, donated a 17th bell.

Dr. William Battle, chairman of the Faculty Building Committee, recommended that three foundries be investigated as candidates for making the carillon’s bells:

Meneely & Co. of Watervliet, New York

McShane Bell Foundry Co. of Baltimore

Meneely Bell Co. of Troy, New York

Soon in the process, the Baltimore foundry dropped out of the conversation, but a British foundry, John Taylor and Co. of Loughborough, England, was added.

“I Am So Confused”

The two leading contestants for the University’s contract were, confusingly, two companies with Meneely in their names and located less than a mile apart in upstate New York. Andrew Meneely had opened a foundry in 1826 in what is now Watervliet. When he died in 1851, his two older sons continued the business. But in 1870, his third son, Clinton, started his own foundry just across the Hudson River in Troy, New York, going head-to-head with his brothers. Naturally both companies wanted to use the family name, and “Meneely vs. Meneely” went to the New York Supreme Court. (Central Texans, think of Black’s Barbecue and Terry Black’s Barbecue, then add two more generations.)

By March 1935, an intense four-month battle between the Meneely cousins for UT’s business was on. In a letter from the Troy side, Joseph Duffy wrote:

“The Watervliet concern has always made a cheaper bell than ours for the market. Outside of the fact that this type of bell is very inexpensive to make, and can be sold at a price of one-half of ours for a bell of the same weight, this bell sold by the Watervliet concern also has the backing of a number of psuedo [sic] musicians … who have established themselves through great publicity as ‘authorities’ on the subject.”

For five single-spaced pages he pleads his case, going negative against “the Watervliet concern.”:

“In [our] up-state community, the relative merits of the two local foundries are well known. Not in forty years has our neighboring foundry installed a chime of bells anywhere in that section, whereas we have placed three chimes in Troy, two in Albany, one in Cohoes, one in Waterford, and one in Amsterdam. As our prices have always been higher than those asked by our neighbors, additional significance is attached to this local preference. . . We understand it is the University’s desire to complete the installation and at a later date to complete the chime of 12 bells. Naturally we feel it is your wish and the wish of those at the University to have as fine a musical instrument as it is possible to produce. But we also feel that you would never accomplish this purpose if an inferior set of bells was purchased in the beginning…”

The Watervliet company appealed to science with the relatively new use of five-point tuning — precision thinning the bell to align the five pitches (partials) inherent in each bell: 1) primary (the strike tone), 2) an octave below, 3) the octave above, 4) the perfect fifth, and 5) the minor third. And true to the letter from Troy, the Watervliet bells were indeed much cheaper.

We know the carillon committee, consisting of Chairman Battle and Chairman Stark, visited Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, as Chester Meneely of Troy wrote:

“In talking with our Mr. Duffy of New York this morning, he informed me … the committee thought one of the bells in the Dartmouth chime was badly out of tune. I hardly think that this could be,” he continued defensively, “as the bells in question were given a most thorough musical test at our foundry prior to shipment and later in the tower. As you may know, bells are very peculiar sound producing bodies and as much as they contain several tones, some of which are more or less prominent and it is very easy for a keen, musical ear to be led astray. This has been demonstrated time again at our foundry and elsewhere by prominent musicians unused to bells to pick out the wrong tones as the strike notes.” In other words, don’t believe your own ears.

But the appeals to science versus subjective aesthetics, client lists and references, all overlaid by aggressive charm offensives and negative portrayals of the competitors, were taking a toll. On May 6, White wrote to his boss, Paul Cret, throwing up his hands:

“The time is growing near when the order for these bells must be placed, if they are [to be] ready for installation as the structure is erected. We have received so much misinformation I fear the committee as myself is quite confused. … In view of the shortness of time, the confusion in the minds of the committee and their inability to make the inspection trip, I believe a definite recommendation on your part will settle the matter. Personally, I am so confused I would be willing to accept either firm.”

A week later, the perceptive Cret wrote back:

“The selection of bells is a problem somewhat outside the range of the architect’s professional training. This is evidently a purely subjective judgment and I am afraid the only kind possible in this case. In the same way that no scientific method to ascertain quality in a painting has yet been devised, the relative merit of two sets of bells will always be a matter of personal opinion. If this opinion is that of a trained musician, it will of course have more weight than one coming from a layman. I found that the opinion of owners of bells is particularly worthless, biased as it is by a mistaken pride and still more by the fact that these owners become accustomed to defects flagrant to anyone else. … I am satisfied that the Watervliet firm is able to supply our needs present and future. … All this being considered, I do not see any reason to eliminate the lowest bidder on this subcontract.”

Eventually Stark and Battle did make a field trip, traveling to Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, to hear the Washington Memorial National Carillon that the Watervliet company had made. This seems to have gone well, for in June, Andrew Meneely wrote, “The bells all to be five-point tuned and each to be as exact a duplicate of the corresponding bill of the Valley Forge carillon as is humanly possible to make it.” Meanwhile, this Meneely had visited Austin, and White visited both New York foundries at Stark’s request.

In a few days, White wrote to Stark that the English firm would have been his first choice: “I am disposed to feel that John Taylor and Company are better equipped to furnish the bells we desire than of either of the American Manufacturers being considered. However, if we are to buy the bells under the PWA [Public Works Administration] provisions, I feel we will be required to use the bells of American Manufacturers.”

Such was indeed the case. Because the Main Building was funded largely by the New Deal’s Public Works Administration, on July 20, 1935, White sent a one-sentence telegram to John Taylor and Co. of Loughborough, England: “ORDER JUST PLACED FOR AMERICAN BELLS ON RULING BY GOVERNMENT.” The deal was done, and the Watervliet concern had prevailed.

The Watervliet foundry closed in 1950; the Troy foundry, 1951.

The Ringers

Shortly after the carillon’s installation in 1936, Jane Yantis, a high school student and the daughter of the building contractor for the Tower, H.C. Yantis, played the first song on the carillon, “The Eyes of Texas.”

But for almost 15 years there was no official “carillonneur.” That changed in 1950.

No history of the carillon would be complete without remembering the man who played those bells for 60 years, or two-thirds of their existence to date. Tom Anderson began his career as a carillonneur in 1952 best known as the younger brother of David, who had been the official carillonneur during the previous two years. Tom was a graduate student studying sacred organ music and ingratiated himself to campus with his wry song choices during the short concerts he played from 12:50 to 1 p.m. Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays: “Blue Skies” as it poured rain or Chopin’s funeral march at the beginning of finals week. Every set began with the Welsh folk song “Ash Grove” and concluded with “The Eyes of Texas.”

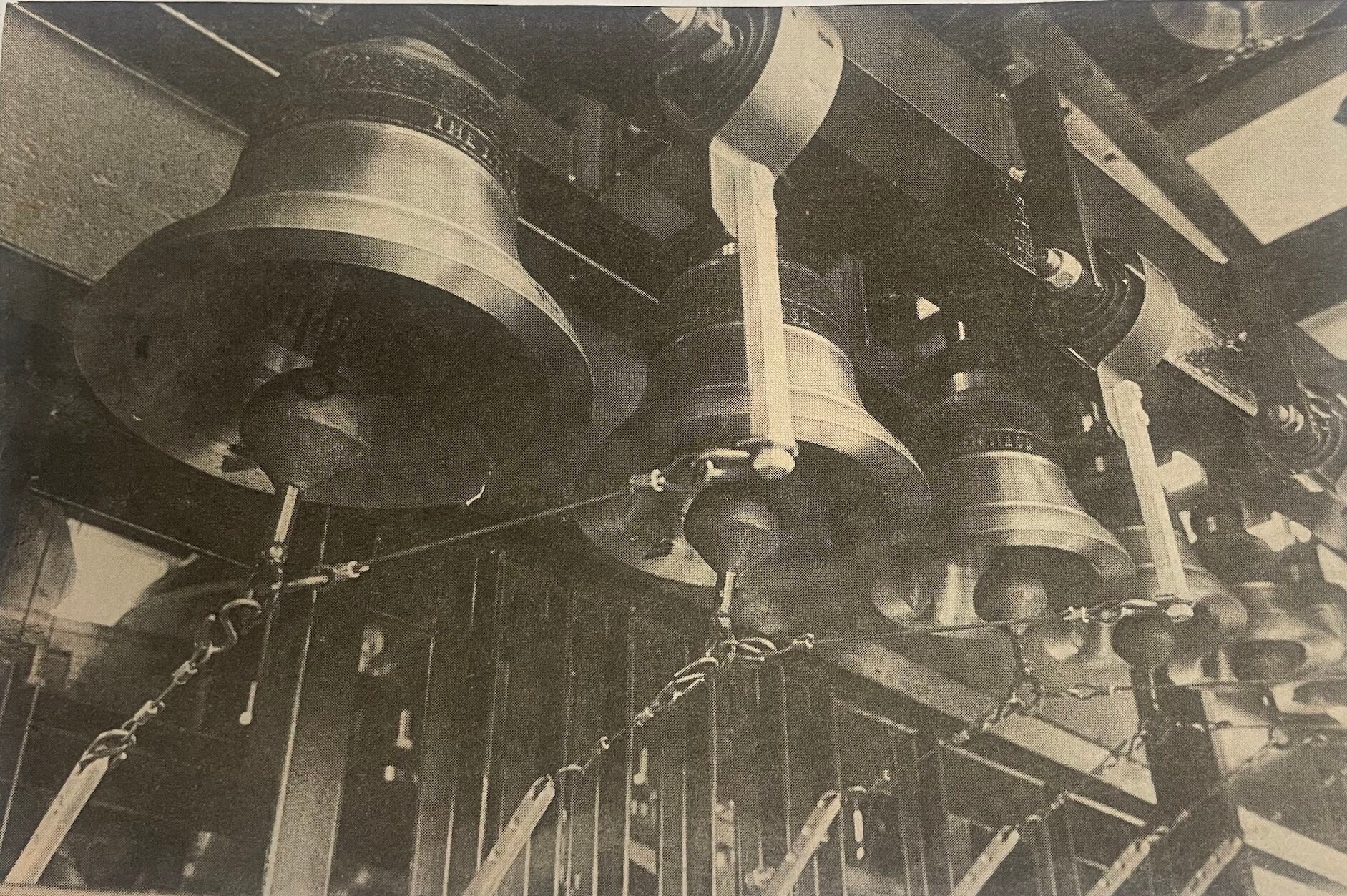

After four years, Anderson turned the console over to others, who played stints of one and two years and all of whom carved their names into the wall near the console: Charles Hunter (1956-57), Proctor Crow Jr. (1957-59), James Moeser (1959-1961), Gordon King (1961-63), Lee Kohlenberg Jr. (1963-65). From 1965 to 1967, the carillon was silent; only the Westminster chime automatically marked the quarter hour as it always had and does still (mi, do, re, so … so, re, mi, do) and the largest bell — the 7,350-pound “bourdon,” a B-flat — chimed the hour. (These five bells are played with hammers from the outside.)

In 1967, President Harry Ransom suggested that Anderson, then assistant director of the International Office, start playing the carillon again. Students made many requests, “Happy Birthday” being the most common, but prefiguring his time in the International Office, he was especially obliging when foreign students would request folk songs from their home countries.

After practicing on a replica of the carillon console on the third floor, Anderson, as carillonneurs do still, would take the Tower elevator to the 27th floor, then make his way through several locked doors and up 55 narrow steps to Room 3002. To actually see the bells, one must continue up a ladder and climb through a trapdoor. After the observation deck was closed during the early 1970s, Anderson was escorted to the carillon room by a police officer for every performance.

From 1972 to 1987, he did not ascend the Tower but rather played the carillon from an electric keyboard on the third floor, with each key activating an electronic clapper inside a bell. This was challenging for several reasons: counterintuitively, one can barely hear the bells from inside the Main Building and Tower at all, which necessitated a microphone in the belfry leading to an amplifier and speaker in the third-floor clavier room. Nor did remotely playing the carillon allow for dynamics — the varying of the volume of the notes.

But all that was about to change.

A Big Upgrade

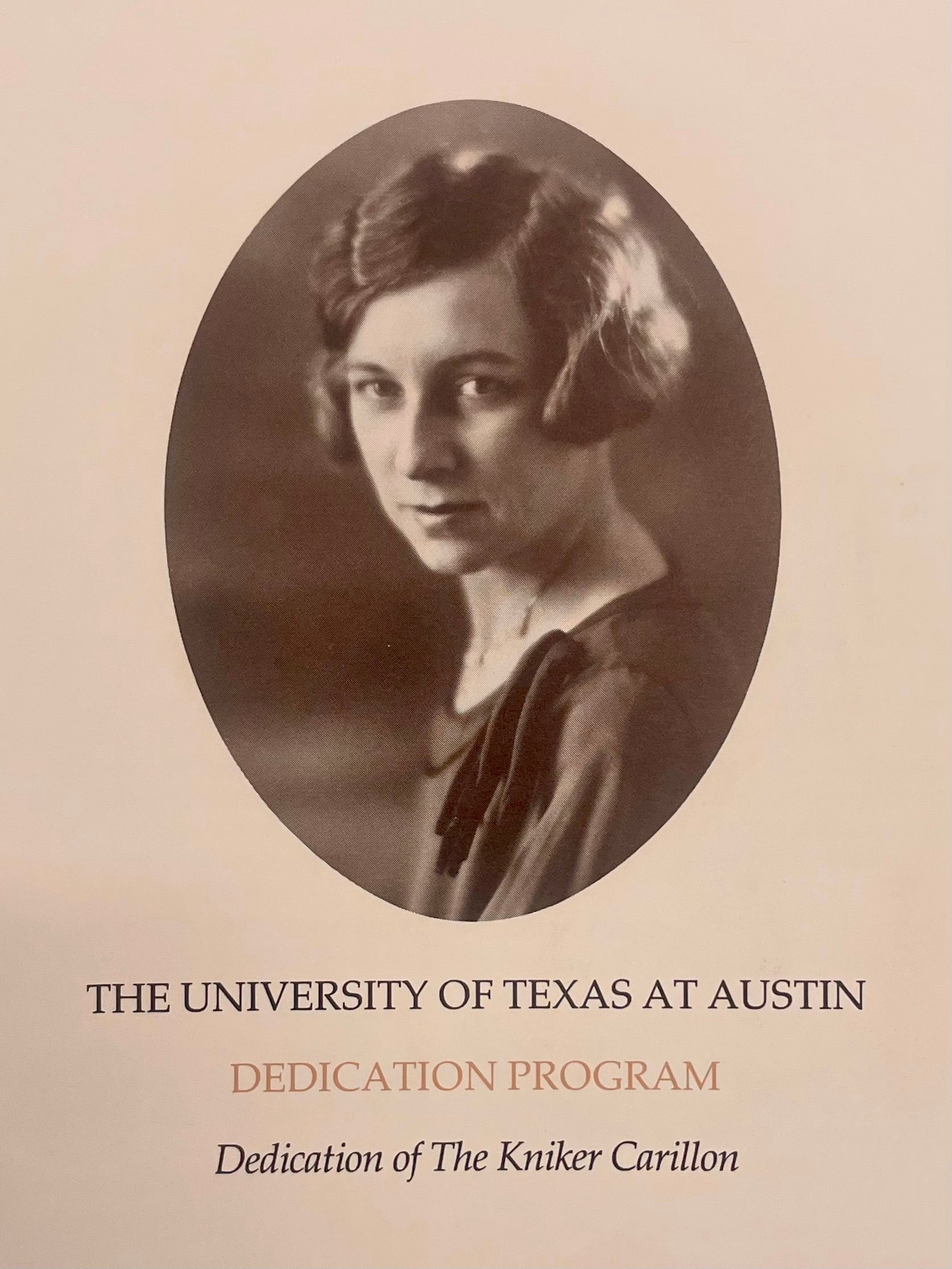

Hedwig Thusnelda Kniker, B.A. 1916, M.A. 1917, had worked as a paleontologist in the oil industry and bequeathed $134,626 to buy 22 more bells for the carillon as well as a new console and installation.

When she died in 1985, her wishes were set in motion. With no federal dollars involved, the new bells were cast by the Petit and Fritsen Bell Foundry in the Netherlands, then installed by the I.T. Verdin Co. of Cincinnati. More notes meant the ability to play more songs, and 56 makes it a concert carillon. However, the C# and B bells would not fit in the elevators, so, the University decided to add bells in the upper register, buying 39 instead of 22. The smallest, high G7, weighs just 20 pounds. The Kniker Carillon is now 56 bells, weighing in at 45,000 pounds, making it the largest in Texas. “I guess this means I’m going to have to start practicing again,” Anderson quipped to one reporter at the time.

On Nov. 14, 1987, the new carillon was inaugurated with an hourlong concert preceding a game with Texas Christian University.

Those thrice-weekly stairs and the full-body performance of arms and legs pushing vigorously was surely one reason Anderson lived to 93, dying in 2016 just three years after his retirement. (Indeed, such was the workout that when the carillon was being planned in 1935, one strong recommendation was that a shower be built just off the console room. “… all the good installations have a shower,” reported the man who had been sent on a fact-finding mission. Alas, a shower on the 30th floor was never built.)

Now, weekly concerts are performed by the University’s Guild of Carillonneurs.

In 2012, the carillon underwent major renovation to repair wear and tear and add a walkway around the bells. The bells were cleaned and rehung.

Just know that whenever you come to campus, the Tower will be there to meet you, with bells on.