If anniversaries are a good time for taking stock, Shakespeare’s 450th birthday on April 23 offers the perfect reason to ask about his plays and poems, and what the future may hold for them.

The writings of this country boy from Stratford are legendary. Thoughts and images came so easily from his pen that other writers have found his talent almost criminal. English had never sounded so good and has rarely sounded that way since. But will this always be the case? Is the status of his writing settled for all time?

Not at all. In fact, Shakespeare’s next century is likely to be less kind to him than the last, and the century after that less forgiving still. This is partly because his words get harder every year.

Looking back, the past four centuries have been good to Shakespeare. School children can no more avoid his plays than a trip to the dentist both of which are supposed to be good for them, although stressful in different ways. Shakespearean playhouses have been reconstructed around the world, making it easy to see his dramas performed in complementary settings.

For those wishing to access his writings in other ways, there are not only countless printed editions, but also versions available on smartphones and tablets. Read, watch or listen. Your choice.

Shakespeare was a star of the movies almost from the time that movies began, so it is no surprise that he has made it into 21st century forms of culture. This is a man, after all, who helped define our sense of culture in the first place. Small wonder that he seems a monument able to withstand the passing years.

In his 55th sonnet, Shakespeare suggested that his writings could last when other things wouldn’t. His “powerful rhyme” would be eternal. But he also realizes, in this poem, that everything changes. Things like “marble,” “the gilded monuments of princes” and “statues” will all go away, ruined by history’s indifferent hand. Everything decays, and only the “living record” of writing would have the chance to cheat time.

As Renaissance led to Enlightenment, Industrial Revolution to the Digital Age, computers have changed our lives in ways that Shakespeare could not have imagined. What he did imagine was time changing everything, something that has come true for his writing.

As our language changes, older forms of English become more difficult. And words themselves are harder, as glowing screens and convenient apps make the visual image, and having things done for us, the norm rather than the exception.

This is why Shakespeare’s place will be increasingly hard to defend. It is pleasant to think that he will remain central to our culture. But the high-water mark of his influence has already passed. It lasted for just a century, between 1870 and 1970.

Since that time, his works have declined in relative popularity, not leveled by the hand of time, but increasingly subject to it. People know his reputation more than his words. Shakespeare will always be with us, of course, but eventually he will be what Geoffrey Chaucer has become: a brilliant author whose works can be read intelligently in the original by few people.

This is regrettable, for Shakespeare seems like one thing that we shouldn’t have to give up in order to have our electronic conveniences. He wrote the most eloquent version of the code we call human character. But he is the most anti-digital of authors. His complexity and richness ask for exceptional literacy, concentration and quiet, things not typically associated with the Computer Age.

Shakespeare’s 450th birthday comes in a brave new world. May his writings live to see his 500th.

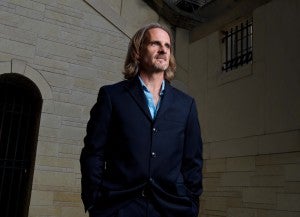

Douglas Bruster is a professor of English at The University of Texas at Austin and specializes in Shakespeare. In 2013, his much-publicized research confirmed that the five additional passages in Thomas Kyd’s “The Spanish Tragedy” were actually written by Shakespeare.