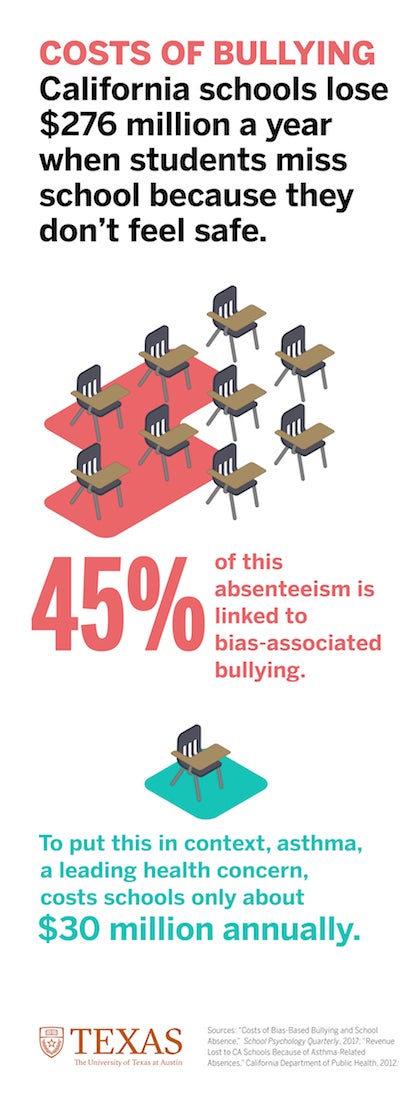

AUSTIN, Texas — When children avoid school to avoid bullying, many states can lose tens of millions of dollars in funding, and California alone loses an estimated $276 million each year because children feel unsafe.

New research from The University of Texas at Austin published in School Psychology Quarterly highlights the hidden cost to communities in states that use daily attendance numbers to calculate public school funding. When children are afraid to go to school because classmates target them because of bias against their race, gender, religion, disability or sexual orientation, schools lose tens of millions of dollars each year linked to this absenteeism.

“Bullying is a big social problem that not only creates an unhealthy climate for individuals but also undermines schools and communities,” says Stephen Russell, professor and chair of human development and family sciences at UT Austin. “We are interested in the economics of bullying and how it can affect a whole school system.”

In the United States, some states including Texas, Illinois and California, use a formula known as average daily attendance to allocate certain school funds. Schools that receive funding based on children’s presence rather than based on total enrollment will have lower revenue when children miss school for any reason.

The research used data from the 2011-2013 California Healthy Kids Survey and information from the state’s Department of Education. Russell and colleagues analyzed surveys of the seventh-, ninth- and 11th-grade students from nearly half of the schools across the state. The team also calculated the average amount of money allocated for each student each day based on average daily attendance funding (about $50).

Analyses showed that 10.4 percent of students reported they missed at least one day of school in the past month because of feeling unsafe. This extrapolates to an estimated 301,000 students missing school because of feeling unsafe and $276 million in lost revenue each year in California public schools.

Biased-based bullying is also costly. Nearly half of the absent students — 45 percent — reported that they missed school and felt unsafe because of being targeted for bias. When Russell and colleagues calculated the lost revenue to California schools each year, it was up to $78 million for bullying due to race/ethnicity bias, as much as $54 million based on a religion bias, up to $54 million for gender bias, as high as $62 million for bias related to sexual orientation and as much as $49 million for disability-related bias. Many children reported they were bullied in more than one of these categories.

“We found a strong link between all types of bullying and school absence,” says first author Laura Baams, also of UT Austin. “Once school districts and boards realize how much funding is lost — especially in those districts that are struggling for funds — we see that it is worth the investment to do something about bullying.”

Not all students subject to bullying miss school. About 19 percent of students experienced biased-based bullying but did not miss school. Still, Russell explains, other effects can occur such as depression, anxiety, poorer academic achievement and health complaints.

“Discriminatory bullying occurs because of who you are or because of who someone assumes you are,” says Russell. “There are clear steps that schools can take to create a safe environment. Professional anti-bullying training and decreasing racism are not only cheaper than leaving the system as it is, but would also promote an inclusive climate for everyone.”

This study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, UT Austin’s Priscilla Pond Flawn Endowment and the Communities for Just Schools Fund. Craig Talmage of Hobart and William Smith Colleges co-authored the paper with Russell and Baams.