The world is abuzz with the recent release of Marvel Comics’ latest franchise movie “Black Panther.” The film is set in the lush land of Wakanda. Wakanda is a fictitious place nestled in an African context that blends cultural aspects reflected across the continent.

Communities around the world have drawn close to this fictitious land, with black people claiming this as a homeplace. But what the space represents for the inhabitants of Wakanda and those across the global African diaspora is not unique or unfamiliar to those who have lived in cities where black people laid down their roots and attempted to build community across the early 20th century.

Houston is one such place.

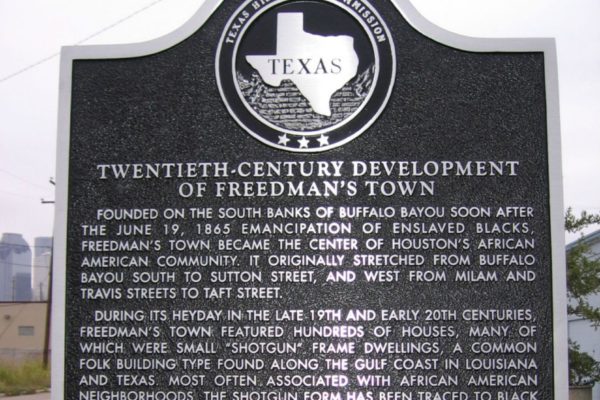

After the ratification of the Emancipation Proclamation and its eventual enforcement in Texas, nearly three years later on June 19, 1865, black people began to settle in the Fourth Ward, or what was also known as Freedmen’s Town.

These individuals came from plantations across Texas and Louisiana in search of a new life of freedom. Black people transformed this racially segregated space into a thriving social, cultural and economic center of black life.

This, however, also served as a homeplace, where solace, protection and community were fostered and sustained. Black feminist scholar bell hooks describes a homeplace for African Americans as a space to seek refuge from the perils of racial hatred and contempt.

As a native Houstonian, one of us, Keffrelyn, understands the power of home and belonging. Although she did not grow up in Freedmen’s Town, her family settled in the Studewood/Independence Heights community in the early 1900s. She spent her formative childhood years living in the neighborhood where two generations of her family lived within a one-mile radius, and where many of her family members, including her sister, still live today.

If “Black Panther” tells us anything, it tells a story about the power of home. Home is not always perfect, and it is sometimes something that we have to fight to establish and sustain. Yet there is often a safety that comes from knowing who you are and from where you come. With its stealth empire, Wakanda created a space not known by the outside world. It was protected from the imperial pursuits that historically became a defining characteristic of postcolonial Africa.

This kind of home safety was also a defining characteristic of African American life in early Houston as African Americans began to settle. Here, safety meant protection from the possibility of harassment and ridicule that came with living in a Jim Crow city in the Southwest. Although racial boundaries were stridently drawn in Houston, African Americans used their homeplace to build and sustain businesses, churches and later cultural centers such as the SHAPE Community Center, which is still in existence.

“Black Panther” also speaks to issues of visibility and affirmation that are also key attributes of home and place. To be affirmed by home is to be seen and recognized, particularly when the larger society fails to do so.

Like Wakanda, where people of African descent are central to all aspects of life, even while resisting societal perceptions of Africa and the African diaspora as racially and culturally deficient, the history of Freedmen’s Town similarly affirms the culture and beauty of African Americans in Houston. This invisibility is in plain sight and harkens to Ralph Ellison’s description of the essence of what it means to be black in the U.S. in his beautiful book, “Invisible Man.”

Simiar to Wakanda, where cultural celebrations and politics were deliberated in the community, spaces such as Freedmen’s Town served a similar function in Houston. Although isolated from the wider world, such isolation helped to foster deep binds of community.

Freedmen’s Town, like other historically black communities across Texas and the U.S., has changed dramatically due to encroachment and gentrification. Yet the legacy of these early settlers remains present in the sociopolitical and economic landscape of the space. In Freedmen’s Town, specifically, African American community activists have persistently fought against the efforts to push African Americans out from these neighborhoods.

Fundamentally, whether it be the context of Freedmen’s Town in Houston or the shiny Afro-futuristic empire of Wakanda, the idea of home and place are central to the politics of race in America. In some respects, perhaps Wakanda is less a fictitious space than a representative space that is illustrative of the past, present and future for African Americans.

Keffrelyn Brown is an associate professor of cultural studies in education at The University of Texas at Austin.

Anthony Brown is an associate professor of curriculum and instruction at The University of Texas at Austin.

A version of this op-ed appeared in the Houston Chronicle.

To view more op-eds from Texas Perspectives, click here.

Like us on Facebook.