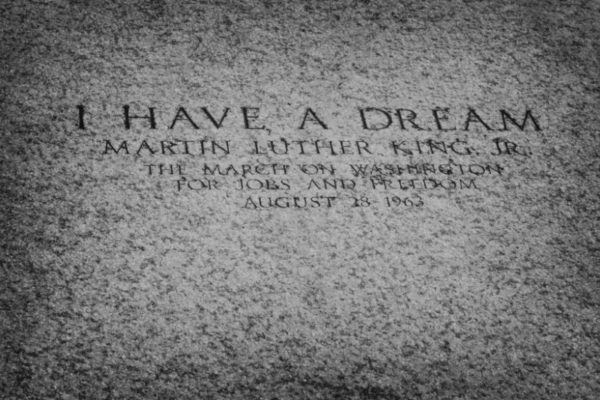

Fifty years ago, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered by American-born terrorist James Earl Ray. At the time, King was under FBI surveillance, and two-thirds of Americans held an unfavorable view of him. The causes he embraced — not only civil rights and racial equity, but also opposing the Vietnam War and poverty — forced the nation to confront uncomfortable moral realities of the American experience.

King unflinchingly held a moral mirror to the nation’s face. He astutely observed that our nation suffered from a “poverty of the spirit,” noting that despite our technological advances, “we haven’t learned to walk the Earth as brothers and sisters.”

A half century after his assassination, we should ponder what King would make of modern U.S. society. There have been considerable achievements for people of color that portend social justice — an African American president, a Latina Supreme Court justice, the adopted son of a Syrian immigrant becoming the world’s greatest technology innovator.

I suspect King would note the enduring, sickening sameness of white supremacist violence through arson, guns and bombings. These horrifying actions in churches, schools and communities show that the advancing years have not eliminated immorality and evil from the American character.

People similar to Bull Connor and George Wallace still litter the political and social landscape, making brazen appeals to uphold white supremacy. Too often, people place economic or political concerns over the immorality of prejudice and bigotry, exemplifying King’s caution: “For evil to succeed, all it needs is for good men to do nothing.”

The way forward is to underscore that racial divisiveness is morally abhorrent, and to deliver electoral consequences to those who endorse them. When those seeking public office do so by scapegoating and casting blame on the powerless, they are unsuitable for public office.

King also interrogated the concept of allyship in 1967, challenging the “white liberal who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice, who prefers tranquility to equality.” This admonition is as real today as it was when King wrote these words, reminding allies that “The Negro has not gained a single right in America without persistent pressure and agitation.” Noting the criticisms toward civil rights activists accused of pressing too hard and creating a backlash, King stated, “the hatred and hostilities were already latently or subconsciously present.” Critiques of activists supporting movements such as #BlackLivesMatter, immigrant rights, #MeToo, and #NeverAgain illustrate this point. Motivated by a regard for justice and human rights, these activists are “bring[ing] out the hidden tension that is already alive.”

For those pessimistic about social progress, there are examples of hope today. As an educator, I see a generation of youths inspired to act — through organizing, protests and direct action — to shape an equitable world. Results are not immediate, and progress can seem slow. These young people understand they are building on the work of King, who was 26 when he led the Montgomery bus boycott.

The Moral Mondays movement, which began in North Carolina and is now in 12 states, is also an inspiring example. Led by the Rev. William J. Barber, this coalition of activists, faith leaders and champions of justice has engaged in the debates about health care, educational spending, women’s rights and LGBTQ rights. Perhaps these messages – termed “neither left nor right; neither conservative nor liberal” – are resonating.

In 2018, there are reasons to surrender to hopelessness: mass murder in schools, domestic terror paralyzing communities, and a climate of fear that tears families apart. Our social ills resemble those of April 3, 1968, when King stated that if given the opportunity to live in any period in history, he would have chosen that time, because “only when it is dark enough can you see the stars.” King would recognize the youthful stars I have the privilege of interacting with virtually every day.

Moral courage is not always popular, and King paid the ultimate price for taking a stand against injustice. Fifty years on, we should reflect on his sacrifice and shoulder the moral burden of combatting racial, gender, economic and all other forms of inequality — however unpopular our stand might be — to create a more just society.

Richard J. Reddick is an associate professor of educational leadership and policy at The University of Texas at Austin, where he also holds courtesy appointments in the Department of African and African Diaspora Studies, the Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis, and the Warfield Center for African and African American Studies.

A version of this op-ed appeared in Fortune.

To view more op-eds from Texas Perspectives, click here.

Like us on Facebook.