Historian and professor Daina Ramey Berry teaches in the History and African & African Diaspora Studies departments at The University of Texas at Austin and has received the Hamilton Book Award for her latest work, “The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation.”

Here, she tells us how 10 years of research led to discoveries that force us to relearn what we thought we knew about slavery in America — such as a slave cadaver trade that supplied America’s top medical schools and trained future surgeons.

She’s just won the most prestigious literary honor given at The University of Texas at Austin, but historian Daina Ramey Berry didn’t set out to write this book, this way.

“I originally wanted to write a book that clarified all the numbers,” she tells me one November morning. “I spent almost seven years crunching numbers, going to the archives, and pulling documents.” Berry wanted to create a regional analysis of slave prices throughout the South — from upcountry to lowcountry, from Virginia’s Appalachian Mountains to Alabama’s Gulf Coast and beyond.

As we talk in her office, she pulls a roll of gold seals from her bag. The foil stickers are reflecting the sunlight coming through a window behind her, and I can’t read all the words, but “WINNER” is clearly visible. So is Berry’s smile, which is growing larger. “These just came in!”

Her newest work, “The Price for Their Pound of Flesh,” has won the Hamilton Book Award. The seals will go on her book covers and are a gift from the University Co-op, which bestows the award each year to a UT faculty or staff member who has written the best book-length publication. (And at a place like UT, that’s saying something.)

As she puts the seals on the table between us, she continues. “I thought, what if I write this book and I have all these numbers? Then I could really give a sense of how enslaved people were valued.” She wound up with a database of 88,000 individual slave prices, including winning auction bids, plantation estate appraisals, and slave insurance costs.

“That sounds like a lot,” she agrees, seeing my eyes widen at the number, “but out of the 4 million who became free in 1865, it’s not hardly representative.”

So she stopped. She scratched the regional analysis idea altogether.

“That’s what was driving me at first, but I kept seeing something different. I’m looking for valuation, but enslaved people are telling me how they see value. And I said, that’s it. That’s what’s missing.”

She realized that deep within these documents were the voices of the enslaved themselves. Stories, reactions, reminiscences jotted down along with the market prices and slave inventories she’d been tracking for nearly a decade.

And that led Berry to ask the fundamental questions: How did the enslaved feel about slavery? How did they value themselves?

“Whether alive or dead, enslaved bodies were commodified”

It had nothing to do with actual dollar amounts, of course. They didn’t care whether their sale price was high or low, Berry says. What she uncovered, however, was a system of commodification that upends how we’ve been taught to think about the domestic slave trade. And before we can understand how slaves valued themselves, it’s necessary to understand how they were rated as objects, “from womb to grave.”

“I had to stop working for two weeks,” Berry tells me, reflecting back on a day when she found evidence that a baby, only 3 days old, was separated from her mother and sold at auction. “I recorded the sale into my spreadsheet, then closed my computer and walked away.”

Berry knew slave families were often separated, but she also had been given the academic reassurances that babies and small children were always kept with their mothers. “But that’s not true,” she insists. “I kept thinking, they’re not going to get any younger than this. They can’t.” And then they would. She dug further and found children — 2 years, 1 year, 6 weeks, 3 days — sold away from their parents.

But through the process of methodically recording tens of thousands of market prices, she was able to observe trends. Girls and young women, on the verge of fertility, were sold at a premium for their “increase,” a term used in antebellum America to describe a female slave’s anticipated ability to breed. The possibility that she could produce offspring, regardless of any other attribute, made her a good investment, the same way a rancher might buy a new heifer or sow. Her offspring could be kept to work the plantation or could be sold — at any age — to bring in additional income.

Some estates, in fact, had more money tied to their slaves than to their crops.

This is a tour de force of scholarly research and powerful writing. 'The Price for Their Pound of Flesh' is an amazing book, well worthy of UT’s Hamilton Book Award.

That asset didn’t necessarily disappear from the books when a slave died, either, and this is perhaps one of Berry’s biggest discoveries. American medical schools’ reputations rested heavily on their ability to train students as surgeons, and that required a steady supply of good quality cadavers. Schools such as Harvard, Dartmouth, and the University of Virginia were competing with their European counterparts like the University of Cambridge — and losing. In the States, acquiring cadavers was difficult. The only legal sources were executed criminals and those who died in almshouses, and schools needed more. Social disapproval of human dissection complicated the issue further.

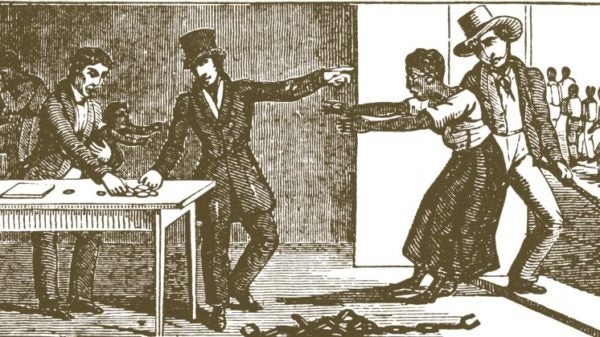

But slaves, Berry found, were different. Because they weren’t valued as humans, their bodies could be openly sold (or stolen). She uncovered a second domestic slave trade, one that profited from dead slaves instead of the living.

Ghost Value and Soul Value

“The field of gynecology grew out of slavery and, in particular, enslaved women’s bodies,” Berry writes. All of American medicine, actually, came to rely on supplies of slaves, and the cadaver trade was soon managed like a seasonal crop, with best practices for sowing, gathering, and storing goods to maintain freshness. Medical school dissection classes followed the harvest.

Berry calls this a slave’s “ghost value,” and it was a booming business. Owners could continue profiting from their slaves even after death by responding to advertisements and making arrangements to transfer the deceased. Even in death, she explains, enslaved people’s bodies weren’t their own, and many were handed off to their next owners without the benefit of funeral rites or the honor of being grieved.

Grave robbing was rampant as well. Performed by “resurrectionists,” robbing didn’t only target slaves — graves of nonblacks also were pilfered — but whites benefited from the ability to guard and physically fortify their family graves, and they were also helped by the social stigma attached to stealing Christian corpses. (Slaves’ religious and spiritual beliefs weren’t validated.) So resurrectionists often found their most reliable, easy sources in slave cemeteries. Even worse, some were slaves themselves, working as medical school janitors during the day and grave robbers at night.

My soul began singing, and I was told that I was one of the elected children.

But slaves weren’t tied to their human bodies. Instead, Berry says they recognized their intrinsic value as beings — what she calls their “soul value.”

The evidence is in their last words to each other at auction — the mother who holds her child’s face in her hands one last time and tells him they’ll meet again. It’s the slave who cuts off her fingers to make herself less desirable to a new owner so she can stay with her family. It’s the slave mother who leaves her baby in the woods, alone, while she looks for a safer place to hide. And it’s the slaves — sometimes joined by ally abolitionists — who resort to riots in the pursuit of emancipation.

They could accept the terms and the risks because they didn’t attach the same monetary values to themselves as white society did. They didn’t participate in their own commodification except to buy each other out of slavery, once one family member had been granted freedom. They believed their souls, if not appreciated in this life, would be valued in the next.

Recognizing Humanity

These findings don’t complete our understanding of American slavery though. We’re still unpacking our past. “We don’t have a consensus on this history yet, and I’m fine with that,” she says. “We’re in that stage in the historiography of peeling back the onion and learning more about all these different experiences.”

Even her own students will say, “But wait, that’s not how I learned it.” Scholars, she says, continue to unearth new things, and she points out that we’re still in a time when black people have not been free in this country for as long as they were enslaved.

“Once we have all this on the table, then we can put the puzzle pieces back together and say, ‘This is the grand narrative.’ But we’re not ready for a grand narrative of slavery just yet. We’re not even close.”

Berry looks at her phone and realizes she’s late for an appointment, having stayed longer than we planned. She doesn’t rush me, though, and I’m grateful. This isn’t how I learned it either, after all, and there’s so much I still don’t understand. As we wrap up, I ask whether I can have one of her gold seals for my book, and she graciously obliges. Still running late, still not rushing. While she places one of the stickers on the cover, I take the opportunity to ask one final question. In her book, she writes that she demands recognition of the self-actualized values of their souls. How do we begin to do that?

“Recognize their humanity,” she says, looking up. “You know, right now we’re stumbling on the bones of formerly enslaved people. There are cemeteries and graveyards that have not been kept up, and we know of other burial grounds still unmarked today. We can do something about that. We can clean these places up and allow them to be a final resting place. Their labor was so tough while they were alive. Why can’t we at least honor them in their death?”