In September 2018, UT Austin’s Office of the Vice President for Research partnered with the School of Design and Creative Technologies Extension to imagine a first-of-its-kind, invitation-only retreat called Associate Professor Experimental (APX) to inspire faculty members to put down their phones, turn off their email, and get to know their peers’ research expertise. The goal was to create a space where faculty members from different scholarly backgrounds could come together to solve interesting problems in new ways. To everyone’s surprise, it worked even better than they had hoped.

“We looked at each other, and I wondered, what should we do? I wasn’t really interested in any other type of research, and I think neither were you.”

Salvatore Salamone, a civil engineer, is sitting with neuroscientist Michael Drew. He’s remembering back to a three-day retreat called APX they both attended last fall. APX stands for Associate Professor Experimental, and its aim is to bring newly tenured faculty members together to meet one another, learn about every one’s work and interests, then break off into pairs or small groups to come up with unique research proposals. The best ideas would be funded on the spot by the Office of the Vice President for Research, but there was a catch: You couldn’t partner with someone from your own academic department.

On the final day, however, Salamone and Drew realized that everyone had a team except them. Groups were already well into proposal-writing mode by that point, so the two lone professors made the only obvious choice.

“We said, let’s go play tennis,” laughs Salamone. But it had started raining; not tennis weather.

Without many options left, they decided to sit down and talk, but neither was optimistic. Even after two hours of brainstorming, they hadn’t made much progress. That’s when Salamone pulled up a video, and Drew says it was their aha moment.

“It was a video from his lab of a ping-pong ball bouncing along the fuselage of an airplane. They were using sound waves to detect exactly where the ball hit,” Drew explains. Salamone places sensors in structures such as buildings and bridges (or airplanes) to locate points of impact — from an earthquake, for example, or a ball — that can’t be detected visually.

“I’m a neuroscientist and he’s an engineer, so right off the bat it didn’t seem like there’d be any way for us to collaborate,” says Drew. “When I saw that video, though, I realized the problem he’s trying to solve is actually very similar to a problem I’m trying to solve.”

Listening for Anxiety

Drew’s lab in the College of Natural Sciences uses mice to study anxiety, mood, and memory. The problem, it turns out, is that it’s pretty hard to know what a mouse is feeling by looking at it through a cage. “It’s virtually impossible to tell if it’s really, really afraid or just sleeping,” he concedes with a half-smile.

That’s where Salamone’s sensors come in. If ultrasonic waves can reveal where a ping-pong ball hits the body of a plane, maybe they can also reveal a mouse’s tiniest twitch or startle reflex — things that are easy to miss with the naked eye. If they could use Salamone’s expertise to design a cage floor that can track a mouse’s movements so they could analyze the sound wave data, they might be able to hear a mouse’s different behavioral states that they otherwise wouldn’t be able to distinguish.

They decided to find out.

For the engineer, it would be the chance to use his training to invent a new type of equipment that could be useful in laboratories around the world. For the neuroscientist, it’d be an opportunity to learn about anxiety in a way that no one else in his field has tried before, the results of which could improve how we treat anxiety in humans.

I'm a neuroscientist and he's an engineer... When I saw that video, though, I realized the problem he's trying to solve is actually very similar to a problem I'm trying to solve.

Talking About Violence

At the same time Salamone and Drew were thinking about sound waves, another group had been loosely forming over the previous days. They were curious about whether their backgrounds in gun culture, TV news, and Mayan linguistics could help them turn out a research proposal worth funding.

But Mary Bock, a journalism researcher in the Moody College of Communication, admits she had second thoughts after agreeing to participate in APX — she was worried it would be time-consuming, a gimmick — but says she was a quick convert.

Once Bock met Harel Shapira and Danny Law, an idea started to form. Shapira, a sociologist, has been embedded in gun schools and ammo clubs around the U.S., studying how members talk about guns and homicide. Law is a historical linguist who’s interested in using statistics and computer science to examine large data sets of words to uncover patterns. Bock looks at how TV news reporting frames the way people think about domestic violence.

“Methodologically,” she says, “we all come from different backgrounds but not wildly different intellectual paradigms. We have common interests with disparate approaches.”

For Shapira, it clicked at dinner one evening during APX when Law began talking about linguistic communities — groups of people who share the same language or the same way of talking about things. “He used that phrase, which is something I’d never heard of. We in sociology never use that [term], but it was exactly what I felt like I was hearing in these gun schools.”

With the help of journalism graduate student Ever Figueroa, the research team wants to see whether there’s a linguistic community among police officers and, if so, what words they use to talk about justifiable homicides — instances in which someone is killed, but no charges are filed against the person responsible for the killing. They’re currently combing through three years of statewide homicide data with the goal of conducting an interpretive analysis of police reports: What words do they use to describe the crime scene, victim, or motives? What does the sentence construction look like? Are there differences from one police department to another?

“How you talk about something is what makes it a thing,” Shapira says, and his team wants to understand how language affects the way police and, ultimately, the public think about homicide in Texas.

“I hate icebreakers.”

Bock describes being in APX a bit like throwing everyone in a jar, shaking it up, and seeing what sticks together, but those interactions weren’t accidental.

“We weren’t allowing them to start by sinking into their old ways,” Doreen Lorenzo reveals. Lorenzo is the assistant dean of the School of Design and Creative Technologies in the College of Fine Arts.

When Vice President for Research Daniel Jaffe and Associate Vice President Jennifer Lyon Gardner came up with the idea for APX, they knew they couldn’t host a typical conference and expect non-typical results. They asked Lorenzo to guide the planning process. Together with the School of Design’s Julie Schell and School of Architecture associate professor Tamie Glass, she helped conceptualize and facilitate the multiday retreat.

“From the moment they stepped off the elevator, we engaged them,” says Lorenzo.

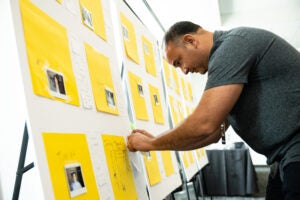

“We wanted it to feel like they were crossing a threshold when they arrived, that they were joining something special,” agrees Glass, whose expertise is designing for human behavior. She oversaw all the tactile elements at APX, from name badges and signs to table settings and game elements, in order to encourage specific social interactions among attendees.

Yes, also known as icebreakers. One thing everyone agreed upon was that faculty members should leave their CVs at the door. They’d all recently been promoted and received tenure; everyone was on the same footing. Instead of feeling the need to define themselves by their accomplishments, people were initially seated together based on their dream jobs and had to introduce themselves by learning people’s fun facts — even the person whose fun fact was their hatred for icebreakers.

But those elements, while lighthearted and playful, were intentional. Each planned interaction was designed to open the door to dozens of spontaneous ones.

Design Matters

And it worked. No one left early or ditched partway through. The last day was dedicated to proposal writing without distraction, and all teams produced a finished pitch on time. And even though Jaffe and Gardner intended to fund only a few proposals, they were so impressed with the results that they decided to fund them all.

Even more impressive, says Schell, is that the event had legs. “We were blown away by the research pitches, but what’s more impressive to me is that APX has already led to a spin-off project called Shut Up & Write, and that was all their idea. The faculty members came up with that because they loved having uninterrupted writing time at APX. We took their feedback and created something new from it. That’s good design.”

For Jaffe, UT Austin’s vice president for research, APX’s strength is that it gives faculty members permission to try something new. “Here, they have the opportunity to take risks they would not have dared to take earlier in their careers. Researchers, scholars, and creative artists can find exciting new directions for their work that might never occur to them if they simply woke up one day with their promotions and went back to work in their own areas of specialization.”

Funding is a big motivator, of course, but to Gardner’s surprise, most attendees said it was the relationships they built with their colleagues across colleges — not the money — that they valued the most.

Given the positive feedback and new research projects that are underway because of last year’s inaugural workshop, Gardner says they’ll definitely be hosting APX 2019. “We’ve seen how well this curated, design-conscious retreat works to stimulate new scholarship among the faculty, and we want to keep building the tribe of APX thought leaders.”

“Plus,” she adds, “it’s not a bad backup if you can’t get out to play tennis.”