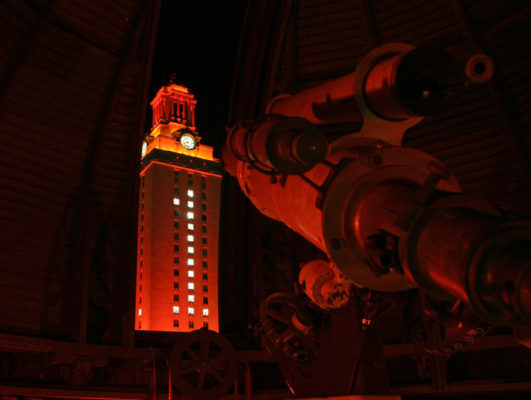

When the sun sets in West Texas, the Davis Mountains come alive. Javelinas rustle through the shrubs looking for food, moths flit about, and the telescopes of the McDonald Observatory turn to the stars.

West Texas has some of the darkest skies in the United States. The absence of light and the dry desert air allow for perfect sky viewing. And a dedicated local team of staff members at McDonald enables international collaboration.

Every night, the observatory’s telescopes and their operators collect images and data from nearby stars and faraway galaxies. The information is immediately beamed to the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) via an underground fiber-optic cable, making what would be a seven-hour car ride to Austin in a split second. Astronomers in Austin, Pennsylvania, Germany and beyond can then survey the sky from computer screens.

In terms of astronomical time, the McDonald Observatory has barely existed. But during its 80 years, its staff and faculty have made essential scientific contributions. Planets outside our solar system have been discovered, passing comets have been detailed and black holes have been measured. The telescopes have captured star births, star deaths and star collisions.

This summer, Sandra A. Catlett, the executive assistant to the director, organized a conference to mark the observatory’s 80th anniversary. Staffers, faculty members, funders and fans all traveled to McDonald to attend talks, discuss discoveries and gaze at the stars.

A resolution passed by the Legislature earlier in the year in honor of the anniversary, signed by Gov. Greg Abbott, recognized “the staff and researchers at the McDonald Observatory for pushing the frontiers of technology and science.”

OTHERWORLDLY

The McDonald Observatory started with a surprising gift. In 1926, William J. McDonald, a wealthy banker from Paris, Texas, bequeathed the majority of his estate to The University of Texas to found an observatory. UT didn’t have an astronomy department at the time, and so the project stalled.

A few years later, Otto Struve, a world-renowned astronomer at the University of Chicago, proposed a deal: If UT funded the observatory, the University of Chicago would operate it for 30 years. The universities forged, as former McDonald director Harlan Smith described it, “a union formed with Chicago brains and Texas money.”

The regents agreed to the plan, and Struve got to work. He oversaw the design and production of an 82-inch reflecting telescope , then the second-largest in the world, which is now named for him. The size refers to the diameter of its mirror, which an optical telescope uses to collect and focus light from the sky. The larger the mirror, the better it can reveal objects that are dimmer and farther away.

Smith was the first Texas director of the observatory after UT took over management in the 1960s, and he immediately expanded the program by hiring several new faculty members. He updated the 82-inch and oversaw the production of a new telescope, a 107-inch model that now bears his name.

One of Smith’s most consequential hires was that of research professor Bill Cochran. Smith met Cochran at a scientific meeting in the mid-1970s and told Cochran he had foreseen his coming to McDonald in a crystal ball. Cochran was charmed: He came to UT in 1976 and hasn’t left.

Cochran started his career studying our immediate neighborhood.

“I was really interested in the planets in our solar system. I was looking at the structure and composition of the atmospheres of the outer planets,” Cochran says.

By the mid-1980s, however, he began to shift his focus.

“I was running out of planets,” Cochran says.

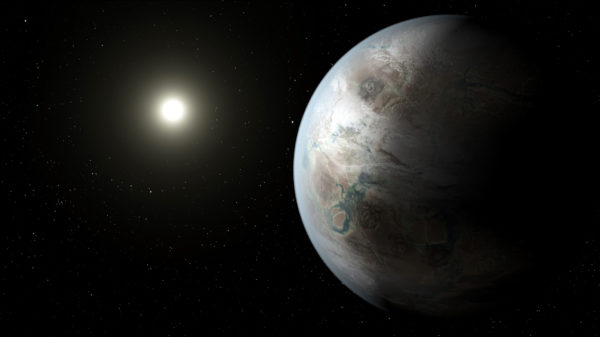

Cochran became interested in planets outside our solar system, which are called exoplanets. Although none had ever been discovered, he assumed other stars must also have solar systems.

Finding them, however, is a difficult task. Stars are large and bright, while planets are dark and dull.

“The light from the planet is about a billion times fainter than the light from the star,” Cochran says.

First-class telescopes such as the ones at McDonald are designed to reveal faint objects, but revealing planets as they orbit their bright stars is nearly impossible; they disappear in the glare.

“It’s like trying to find a firefly in a floodlight,” says Taft Armandroff, the current director of the McDonald Observatory.

Cochran had to get creative.

“Given the technology of the 1980s, we had to figure out how to use the light we had, which is the light from the star, to reveal the presence of the planet,” he says.

Stars, like all celestial objects, are constantly moving. Stars that have orbiting planets can have their movements slightly disrupted. Cochran designed a program that would detect these changes and use them to infer the presence and mass of orbiting planets.

Cochran started his planet detection program in 1989, and in 1996 he officially discovered 16 Cygni Bb, his first exoplanet, using the Harlan J. Smith Telescope.

EXPANDING HORIZONS

In the mid-’90s, just as Cochran was discovering his first exoplanet, the observatory was busy expanding its capabilities. UT partnered with Penn State University and two German universities to build the Hobby-Eberly Telescope (HET), one of the largest optical telescopes in the world. Its segmented mirror spans 36 feet.

The new telescope brought new personnel. When senior research scientist Matthew Shetrone came to interview at McDonald in 1997, he says staff members were so busy installing the HET that they couldn’t spare the time to interview him.

“They said, ‘If you’re willing to climb up in the truss and help install a mirror, we can chat while we do that,’” Shetrone says.

He spent the interview in a hard hat and a harness, helping install some of the HET’s 91 mirror segments.

“I was wearing nice clothes!” Shetrone says with a laugh.

The moment illustrates how dedicated the staff members are at McDonald. Shetrone built on that dedication and has spent the years since in West Texas helping astronomers all over the world.

“I am a service astronomer,” Shetrone says. “Most of my effort goes into making sure other astronomers do great work. I get a real thrill from hearing about data I helped collect.”

The highly technical roles at McDonald require skilled staff members who are passionate about their work.

Emily Mrozinski, the head of the HET’s mechanical team, says she had always been drawn to UT.

“I grew up in Austin with a view of the UT Tower,” she says.

After studying engineering at UT and working as an engineer and a teacher, Mrozinski applied to McDonald during a period of transition.

“The truth of the matter is my mom was dying, and I was going to become a contemplative nun,” she says.

She had planned on the job being temporary: “My plan was to move here, work on this cool telescope while I looked at monasteries.”

But Mrozinski fell in love with life on the mountain, and her plans changed.

“I now have a husband and two children,” she says.

The HET allowed for a number of new projects and initiatives and helped aid ongoing efforts at McDonald. Cochran was able to expand his exoplanet search and discovered several new planets.

As technologies advanced, UT astronomers hatched a plan to increase the effectiveness of the telescope. They took the HET offline in 2013 and started a multiyear process to improve its capabilities.

“This was an insane thing to do for many people’s standards,” Shetrone says. “You take a perfectly good working telescope, and you take it apart and upgrade it to hopefully do something much better.”

In order to expand the telescope, HET staffers had to take apart old equipment, design and order new instruments and reassemble those pieces back at the telescope.

Mrozinski was essential to the effort. She handled the complicated logistics of the removal and transport of tons of equipment.

“We had to take the old bridge off, which was done with a massive crane,” Mrozinski says. “It took probably about a year.”

When that task was done, she had to oversee the installation of the new bridge, a moveable structure that spans the reflecting mirror and holds the telescope’s instruments.

“The bridge itself is 25,000 pounds,” Mrozinski says. “Another 20,000 or 25,000 pounds of hardware sits on top. All of that had to be disassembled in 5,000-pound components, more or less, and shipped out here.”

Mrozinski had to work quickly to move and assemble many tons of equipment while the dome of the HET was open. Allowing sunlight into the dome can cause fires and destroy the telescope.

“I’ve never had so much fun,” Mrozinski says with a smile.

The upgrade was a success and expanded the HET’s capabilities.

“The field of view of the old HET was about the size of a large crater on the moon,” Shetrone says. “Now the field is about the size of the full moon itself.”

It made an already world-class telescope nearly peerless. The HET is now, by optical aperture, the second-largest optical reflecting telescope in the world.

“We increased the field of view by a factor of a hundred,” Armandroff says.

The upgrades also made the HET more nimble.

“We’re the best telescope in the world for doing time-sensitive work,” Shetrone says. “We can change what we’re doing at a moment’s notice; all of our instruments are available all the time.”

Time-sensitive events, like star collisions, are both rare and short-lived. Although they may have happened billions of years ago, they pass us by in a matter of hours. When gravitational wave detectors pick up on such collisions, McDonald’s equipment jumps into action.

“If anything is detected, the telescope will immediately stop what it’s doing and go across the sky to where the location of this is,” Armandroff says.

Every day I look at a few hundred galaxies that are 10 billion light-years away that no one has ever seen before.

ACCELERATING RESEARCH

McDonald is now undertaking one of its biggest experiments to date. The Hobby-Eberly Dark Energy Experiment, or HETDEX, will look back in time 10 billion years in order to build the largest map of the universe ever created.

The goal of the experiment is to learn more about dark energy, a term scientists use to describe the mysterious forces that drive the accelerating expansion of the universe. Scientists don’t know how or why the expansion is accelerating this way. The term could even be a misnomer.

“It might not be dark, and it might not be energy,” says Karl Gebhardt, a professor of astrophysics.

Gebhardt runs HETDEX. The survey relies on VIRUS, a large spectrograph designed by UT astronomers Phillip MacQueen and Gary Hill that comprises 150 separate instruments.

The spectrographic data VIRUS collects will allow UT astronomers to determine information about the expansion of the universe in the past.

“What we’re doing is looking way back in time, about 10 billion years ago, and seeing whether the expansion was speeding up back then,” Armandroff says.

The stakes are high, and UT is poised to make a substantial contribution to our understanding of the universe.

“If you could really figure this out, it would be Nobel Prize material,” Armandroff says.

UT’s unparalleled combination of resources makes this unique opportunity possible.

“I don’t think we could’ve done it at any place besides Texas,” Gebhardt says.

The HET is one of the largest and most advanced telescopes in the world. VIRUS is the largest spectrograph on Earth. It sends data to TACC, which is the largest university-associated computing resource in the country. And because UT owns a majority stake in the HET, HETDEX astronomers can get unparalleled access to the sky.

“Those four things together are why it works,” Gebhardt says.

The survey has already discovered new objects and returned interesting results.

“Every day I look at a few hundred galaxies that are 10 billion light-years away that no one has ever seen before,” Gebhardt says.

BIGGER AND BRIGHTER

Armandroff has always been drawn to astronomy.

“As a kid, I was fascinated with science. I built my own radio telescope while I was in high school,” Armandroff says with a laugh. “I was probably a really big nerd.”

That early interest and aptitude led him to his role at McDonald.

“If you’d told me I was going to be the director of McDonald Observatory, I’m sure I would’ve chuckled,” Armandroff says. “I feel so incredibly fortunate and privileged to be associated with McDonald and UT.”

Now, Armandroff is overseeing one of the observatory’s biggest expansions: He is the vice chair of the board directing the construction of the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT), a new telescope due to open in Chile during the next several years.

“A number of universities came together and realized that for the next generation of telescopes, they couldn’t do it alone,” Armandroff says.

UT was a founding partner of a group of 12 institutions that designed and funded the GMT.

Although the Davis Mountains offer an ideal star-viewing location, the Atacama Desert in Chile might be even better. The area is one of the driest and clearest places on Earth.

“You can go many weeks without seeing a cloud,” Armandroff says.

The GMT will also be one of the first telescopes to employ adaptive optics, which corrects for distortions caused by Earth’s atmosphere. The adaptive optics system will employ flexible mirrors that can change shape to adjust to subtle atmospheric changes.

“It’s sort of like getting a prescription for your glasses to correct your vision. You correct the vision of the telescope,” Armandroff says.

The system allows for clearer images, and the GMT will compete with space telescopes.

“We will get images 10 times sharper than the Hubble Space Telescope,” Armandroff says.

The telescope is so powerful that it will be able to separate the light from exoplanets from that of the stars they orbit. Cochran will start a new chapter in his planet search.

“What we are really looking for is finding the nearest planets to us that are possibly abodes for life,” he says.

Some projects are already planned, but there is no telling what other science the GMT will enable.

“It’s a golden age,” Armandroff says.

The progress has been made possible by support from inside and outside the university. Recently, Austin philanthropist David Booth donated a large gift specifically for the GMT.

LIGHT-YEARS AHEAD

Katie Kizziar is a lifetime Longhorn. She grew up in Austin and in middle school attended a camp at UT called Careers in Engineering for Women.

She went on to attend UT, study engineering and run that same camp.

“It kind of all started from that education and outreach experience,” Kizziar says.

Kizziar now runs outreach at the McDonald Observatory. She oversees StarDate, a magazine and national syndicated radio show, and the programs at the McDonald visitors center, which include star parties, exhibits, talks and teacher workshops.

The observatory receives 80,000 visitors a year.

“At certain times a year we’re just overwhelmed with visitors,” Armandroff says. “We’re in the middle of nowhere. You don’t just sort of happen upon us. You have to come with some intention.”

“As scientific research institutions go, ours is known within the community as being the most accessible to the public,” Kizziar says. “It’s been something that’s been part of the mission since day one.”

That openness helps advertise and reinforce the culture at the observatory.

“It gives Texas astronomy a big name, so it’s great for recruiting students and researchers and faculty,” says Armandroff. “It also just signals, to Texas and beyond, that we’re a university that really values science, and we’re a university that welcomes everyone.”

The education and outreach also bring astronomy to the public beyond West Texas. Kizziar’s team helps faculty members meet the communication requirements of their research grants.

“We can take the crux of what a researcher is studying and help communicate it to either the general public through the exhibit space or through a teacher workshop,” Kizziar says.

The teacher workshops help bring the science into classrooms and inspire aspiring scientists.

Staff and faculty members also get directly involved in outreach.

“The faculty within our department are amazing. They’re willing to go above and beyond to do something extra at the observatory,” Kizziar says. “They’ll take an hour out of the time they have reserved on the telescope to talk to an audience.”

McDonald continues to innovate and pursue new opportunities to engage with the public.

“We did a training for Texas park rangers,” Kizziar says. “Now, we’ve been contracted by the National Park Service to replicate that program for their training.”

Current outreach efforts focus on educating the public about light pollution. Dark skies are essential for good astronomy, and McDonald works with community partners to keep light from interfering with the research.

“None of this exists if we can’t keep the skies dark,” Kizziar says. “There are so many observatories in the U.S. that have lost their night sky and can no longer do science.”

In all its efforts, McDonald has demonstrated that astronomy can be a great way to inspire young people to pursue science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

“It is the perfect gateway to STEM,” Kizziar says. “It’s accessible. You’re able to look up at the night sky and wonder what is up there and how does that work.”

McDonald staff members know how even brief interactions can affect a visitor. Mrozinski likes to recount a recent encounter in which she allowed a young visitor to rotate the Hobby-Eberly Telescope.

“That’s the stuff that makes kids’ dreams,” Mrozinski says. “It shows them that they, too, could do things like this.”

THE LOCAL UNIVERSE

While McDonald’s telescopes gaze at objects billions of light-years away, day-to-day life “on the mountain” unfolds on a more human scale. People work hard, take care of their kids and contribute to their community.

“There is a staff of 100 people or so who operate this little city in the mountains,” Kizziar says.

Life there is often a family affair. Shetrone got married between the 82-inch and the 107-inch telescopes. Anita Cochran, the assistant director for research support, met her future husband, Bill, here when she was a graduate student. Mrozinski is raising her kids here, where she can show them secret hiking trails only UT staffers can access.

Lauri Lynn Lindquist, the manager of the Astronomer’s Lodge, was first drawn to the Davis Mountains for family reasons. Her son-in-law is a telescope operator at the HET, and her daughter works in the visitors center.

When the couple had their first child, Lindquist decided to leave her home and company in Minnesota and move to West Texas.

“I knew nobody besides my daughter and my son-in-law,” Lindquist says.

Lindquist has been able to help with child care while finding her own sense of community.

“The people on the mountain have been amazing,” she says. “They were really understanding.”

That shared sense of community can help build collaborative relationships.

“People have been working side by side for a long time, and you really get to know people, and you develop all these connections,” Bill Cochran says.

The connections are productive: McDonald staff members have all contributed to world-class science.

“Behind Karl Gebhardt’s talk about dark energy, there are hundreds of staff members who carried out the observations, built the spectrographs, looped all the optical fiber around the telescope and maintained the telescope,” Armandroff says. “If there is an amazing discovery about dark energy, which I hope there is, they’re all a part of that.”

The camaraderie is pervasive, and McDonald staffers are quick to commend their peers.

“I’m always humbled by the people I work with and what they know and what they have to offer,” Mrozinski says.

That feeling is shared by faculty members and administrators.

“It takes really exceptional staff to work on these things.” Armandroff says. “It’s one-of-a-kind equipment.”

McDonald doesn’t just attract a skilled staff. It attracts a passionate staff.

“You can tell,” Mrozinski says. “We love it.”