This might not be as bad as 1918. Or it might be worse.

However it turns out, this is not the first time The University of Texas at Austin has faced a threat of the magnitude of the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. And a review of the University Archives at UT’s Briscoe Center for American History reveals fascinating details of a university dealing the best it could with a historic public health crisis.

Known to history as the Spanish flu (though competing theories have it originating in France, northern China or Kansas), the virus swept the quickly shrinking world in 1918 just as World War I was drawing to a close. Worldwide, it killed 40 million people, four times as many as the war itself.

On the Texas campus, student barracks, where UT recruits had trained and slept during the war, were converted into hospital wards. As the epidemic worsened, classes were canceled twice — for two weeks in October and again for all of December. Football games and rallies, guest lectures, concerts and plays — all canceled for the university’s 2,812 students.

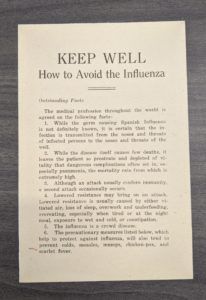

In response, the Executive Committee of the Faculty published a pamphlet, “Keep Well,” with guidance for students and members of the faculty and staff. Much of it will sound very familiar:

“Wash your hands frequently especially before each meal.”

“Stay away from crowds,” and “Abstain from attending meetings, except such as are necessary for carrying out the main purpose of your attendance at the University.”

“Consult a physician as soon as you are sick, be the illness ever so slight.”

And, “If you are at all ill, stay at home.”

Other prescriptions are quaint in their phrasing:

“Keep away from the sick. No right-thinking person will allow anyone but the nurse to come into the room in which he or she is sick with influenza.”

And, “Shun the common towel like the plague.”

Still other cautions are more specific to the era, including, “Don’t cough or sneeze in the rooms or corridors, except into your handkerchief, and don’t shake out your handkerchief in the room.” And the always-good counsel: “Don’t spit on the floor.”

Viruses were barely known to science then, the first having been discovered only in 1884, and, along with bacteria, they were lumped into the category of “germs.” In “Keep Well,” the faculty committee wrote, “While the germ causing Spanish Influenza is not definitely known, it is certain that the infection is transmitted from the noses and throats of infected persons to the noses and throats of the well.”

They were on the right track, though they made no mention of the eyes, also portals for infection of droplet-borne diseases like Spanish flu (which we now know was H1N1) and now COVID-19. The committee continued: “The precautionary measures listed below, which help to protect against influenza, will also tend to prevent colds, measles, mumps, chicken pox, and scarlet fever.” The warnings read like a compendium of everything we knew at the time that prevented illness, along with some nuggets that sound more like prevailing folk wisdom than peer-reviewed science:

“Eat plenty of nourishing food, but avoid overloading the stomach, especially at the evening meal.”

“Don’t sit in a cold room. Don’t let the body become chilled. Avoid wet feet. Avoid all chilling.”

“Avoid overheated rooms, for with a dilated skin, subsequent chilling is very dangerous.”

Preventing the ingestion of germs was another major thrust:

“Look after the health of your digestive organs and the condition of your bowels.”

“See to it that the dishes in your boarding place are thoroughly scalded with boiling water. If this is not done, you are advised to change your boarding place forthwith.”

“Find out if spoons, glasses, and dishes are sterilized at the soda fountain which you patronize. If this is not done, avoid the place.”

But perhaps the Executive Committee’s biggest perceived defense against the Spanish flu was fresh air:

“Have plenty of fresh air. Leave the windows open all night. Air your room during your absence in the daytime. Spend as much time in the open air as possible.”

“Make your calls by taking walks with your company out of doors.”

“Walk to town. If you ride on the streetcar, sit near an open window.”

These were tips for personal health, but fresh air and taking temperature so as to keep the sick away from the well also became the twin pillars of UT’s institutional response:

“Watch your temperature. If you discover a fever in time, rest and care may save your life, or at least save you a long and disagreeable spell of sickness.”

On Jan. 9, 1919, the Executive Committee of the Faculty sent instructions to the rest of the faculty:

“To prevent a recurrence of the influenza epidemic, which would involve a third interruption of the University’s work, the following preventative measures have been recommended by a special committee and adopted by the Executive Committee of the Faculty:

-

- In order to give students more time to go from one class to another and to provide opportunity for the airing of classrooms between classes, the gong has been set to ring, beginning today, January 9, at ten minutes before the hour and on the hour. This arrangement gives an interval of ten minutes between classes, instead of five, as heretofore. Each instructor has been requested to open wide all windows in the classroom which he happens to be occupying, to let them remain open for the next five minutes, and then close them before leaving the room.

- In order to give students more time to go from one class to another and to provide opportunity for the airing of classrooms between classes, the gong has been set to ring, beginning today, January 9, at ten minutes before the hour and on the hour. This arrangement gives an interval of ten minutes between classes, instead of five, as heretofore. Each instructor has been requested to open wide all windows in the classroom which he happens to be occupying, to let them remain open for the next five minutes, and then close them before leaving the room.

-

- To ensure thorough airing of classrooms at night, the janitors have been instructed to open all classroom windows at six, closing them again at five in the morning, so that the room may be warm by eight.

- To ensure thorough airing of classrooms at night, the janitors have been instructed to open all classroom windows at six, closing them again at five in the morning, so that the room may be warm by eight.

-

- In order that there may be no dust nuisance, the janitors have been instructed that all sweeping must be done at times when students are not in the buildings, even if this should require that a part of the work be done at night, and that all desks and chairs must be wiped off with an oiled rag a half hour after sweeping.

- In order that there may be no dust nuisance, the janitors have been instructed that all sweeping must be done at times when students are not in the buildings, even if this should require that a part of the work be done at night, and that all desks and chairs must be wiped off with an oiled rag a half hour after sweeping.

-

- To detect cases of incipient influenza, arrangements have been made for taking the temperature of every student each morning before class. Any student who shows a temperature above normal will be required to remain away from the classes until examined by a physician and reported in good health.

- To detect cases of incipient influenza, arrangements have been made for taking the temperature of every student each morning before class. Any student who shows a temperature above normal will be required to remain away from the classes until examined by a physician and reported in good health.

-

- Efforts have been made to secure the cooperation of the various boarding houses in the sterilization of both eating and cooking utensils.

- Efforts have been made to secure the cooperation of the various boarding houses in the sterilization of both eating and cooking utensils.

-

- Through the efficient help of the faculty, the card catalog of the students has been practically completed. Every student in your class who has not filled out one of these cards whether he has had influenza or not, should be asked to do so without delay. Any surplus cards should be sent to the President’s Office, for use by others who may need them.

- Through the efficient help of the faculty, the card catalog of the students has been practically completed. Every student in your class who has not filled out one of these cards whether he has had influenza or not, should be asked to do so without delay. Any surplus cards should be sent to the President’s Office, for use by others who may need them.

-

- In order that these measures may be discussed by the students in detail, a student convocation has been called by the Students’ Assembly for eleven o’clock Friday morning, January 10, on the campus directly south of the Chemistry Building. All class works will be suspended for this occasion from eleven to twelve.”

Alas, the Executive Committee’s letter did not result in universal compliance, so it fell to President Robert Vinson to deliver a more forceful message four days later:

“To the Instructing Staff:

“It is reported that some instructors are failing to air their classrooms before leaving them, although the University Physician and the health committee of the faculty consider this matter very important for the welfare of the student-body. This airing will take only a few minutes two or three times a day. Before leaving their classrooms, instructors should see that the windows are closed, so that rooms will not be uncomfortable for the incoming classes.”

“Arrangements for taking daily the temperature of the women students have been practically completed, and plans for the men are well under way. It is equally important to detect cases of incipient influenza among the teaching staff, and we hope that each instructor will each morning at home before coming to the class, take his temperature, or arrange with Miss Ruffner, the special University nurse, in Main Building 150, to take it for him.

“Unless the efforts of the health committee are scrupulously observed, a recurrence of the influenza epidemic is sure to follow, with consequences that would be extremely disastrous. Please help us to make effective the measures which have been adopted.”

Lastly, some of the faculty’s guidance struck a philosophical and even a moral note, and resonates just as loudly today:

“Cooperate with your fellow students and the faculty in all sanitary measures for the common good.”

And, “The instructing staff is earnestly requested to impress upon the students the value of life in comparison with momentary pleasure and to urge them to remain away from all social gatherings, moving pictures, and theaters until the danger of contracting influenza is past and notice has been given and conditions have returned to a normal status.”

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes, as Mark Twain is credited with saying. In unsettling times, it might help in some small way to know that, to a degree — as a university and as a society — we have been here before, and we made it through.