Soft and worn publisher’s cloth loosely binds the thin, powdery pages full of tightly squeezed columns and tiny text. The fading covers flash an array of colors, from crimson red to lime green, while some are graced with fairytale scenes straight from a painter’s canvas. The inside pages fade to yellow from age, and names scrawl across title pages, claiming these books as the proud property of schoolchildren, a butcher’s daughter or a Royal Navy captain.

Soft and worn publisher’s cloth loosely binds the thin, powdery pages full of tightly squeezed columns and tiny text. The fading covers flash an array of colors, from crimson red to lime green, while some are graced with fairytale scenes straight from a painter’s canvas. The inside pages fade to yellow from age, and names scrawl across title pages, claiming these books as the proud property of schoolchildren, a butcher’s daughter or a Royal Navy captain.

These scrappy, everyday volumes might not be what you imagine when picturing the cherished early editions of the esteemed English novelist Jane Austen. Yet, English Professor Janine Barchas argues that these cheap versions of Austen’s works were extremely important in defining the author’s popularity and availability to the masses in the 19th century. No scholar hasacknowledged their importance before, Barchas says, and many copies have been lost, making them harder to find today than the surviving copies of Austen’s first editions, which had estimated print runs of 500 to 2,000 each.

“There’s a new category that we now value,” Barchas, the Louann and Larry Temple Centennial Professor in English Literature, says. “And suddenly it’s rarer than those rare first editions, not because it’s more expensive, but because they’re harder to find. Because we didn’t care about them for so long that we threw them out. Now they’re part of the puzzle.”

But years before she came to study these forgotten books, Barchas, who joined The University of Texas at Austin in 2002, had to be convinced even to teach a course on Austen. Why should she teach about an author who already possessed such celebrity — plus a huge fanbase, action figures and plenty of films to showcase her work — when she wanted to teach about authors who lacked advocates and recognition?

“I came to Austen with a certain skepticism and resistance, having always taught the 18th century writers,” Barchas says. “And then I realized that she had read all of the writers that I had been teaching for years and that much of her work grew out of that material.”

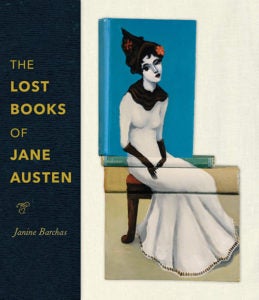

Barchas is now the author of three books and numerous articles as well as curator of several exhibits surrounding Austen. Her newest release, “The Lost Books of Jane Austen,” explores how cheaply produced reprints of Austen’s novels shaped the author’s readership and popularity. The book features 100 photographs of the novels’ intriguing covers, the stories of their owners’ lives and analysis of why these versions are significant.

The working class bought these versions for usually just pennies a copy, Barchas says, an image audiences today might find at odds with the genteel, upper-class reputation that Austen emits.

“It turns out that before Jane Austen was great, she was popular,” Barchas says. “And that may be kind of a strange, bitter pill to swallow for a true critic.”

“The Lost Books of Jane Austen” sprang from a curiosity-driven discovery. On a used-book site, Barchas found a cheap, 1890s reprint of Austen’s first novel, “Sense and Sensibility,” originally published in 1811. After consulting books and databases and conducting searches online, Barchas learned about a Victorian soap company’s giveaway scheme for working-class children in that era. Children collected soap wrappers and exchanged them for prizes, one of which happened to be copies of “Sense and Sensibility.”

That led Barchas to search for other still existing copies that working-class families had owned.

“These cheap books led me in a direction to write an article about using the internet to do unconventional research on books that are not important but are nonetheless kind of a turnkey for certain historical periods,” Barchas says.

Because these novels were so cheaply produced, they lacked the reputation of first editions and rare finds that most book collectors are interested in. Fortunately, Barchas says, two collectors aided in her scavenger hunt and put her in direct access to the copies she was looking for.

“That is when my eyes were open to a whole category of book that I had never interacted with, that were visibly so cheap at the time, and yet visibly appealed to a certain class of reader,” Barchas says. “She was a book prize for coal miners, potters and working men. We think of her now as kind of an elite author, canonical author, even ‘chick lit.’”

Barchas used online ancestry databases and public records to learn about the lives of the ordinary but diverse owners whose names and addresses were written inside some of the covers. Barchas says she found information about occupations, legal disputes and ages in her search for the people for whom these cheap reprints were produced.

Barchas’ most memorable discovery during her research, she says, was the story of Annie Munro from Forfar, Scotland. Annie was raised in a working-class family of eight and received a copy of “Northanger Abbey,” Austen’s last novel, in 1911 as a school attendance prize. Her name, along with the name of her younger sister Florence, and their address are written on the endpaper. But just six months after receiving the prize, Annie died of diphtheria and toxemia at 13.

“That made the process of researching this book no longer academic and distant but made it seem like these were lost individuals who deserve the moment and the history of reading Jane Austen,” Barchas says.

Barchas says she hopes that readers of “The Lost Books of Jane Austen” recognize that an entire social class’s enjoyment and interest in Austen have been ignored by scholars.

“I want them to have that 19th century reader come alive,” Barchas says. “This is not just about lost books, but it’s about lost people from the story.”

Other works

Notable publications by staff and faculty members

Farmscape: The Design of Productive Landscapes

By Phoebe Lickwar

This book examines how agriculture and landscaping can best be combined. Co-author Lickwar is an associate professor and the Landscape Architecture Program graduate adviser.

Biscuits, the Dole, and Nodding Donkeys: Texas Politics, 1929-1932

Edited by Rachel Ozanne

Former UT history professor Norman Brown completed this book before his death in 2015. Ozanne, a lecturer in the Department of History, edited the work and wrote the introduction.

The Last Stand of Payne Stewart: The Year Golf Changed Forever

By Kevin Robbins

Robbins, an associate professor of practice in the School of Journalism, looks at the dramatic final year of golfer Payne Stewart, who died in a plane crash after a winning season.

Barn 8

By Deb Olin Unferth

This novel mixes comedy and political drama in the tale of a plot to steal a million chickens from an industrial farming facility. Unferth is an associate professor in the Department of English.

Recommend a book at pitch@texasconnect.utexas.edu.