AUSTIN, Texas — A medication used as a second-line of defense against tuberculosis shows a promising influence on first-line interventions for fear and anxiety disorders, according to a new clinical study by psychologists at The University of Texas at Austin.

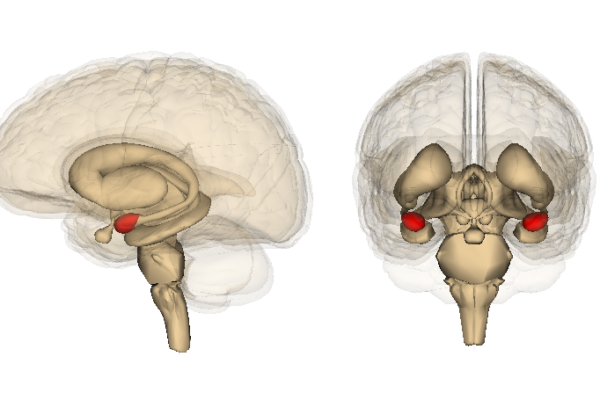

D-cycloserine (DCS) has landed itself on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines for its abilities to stop the growth of bacterial cell walls. But in recent decades, mental health researchers have taken note of the antibiotic’s neurological influence, particularly within the amygdala, the brain’s emotional epicenter — where fear lives.

“Multiple studies have shown that DCS can help cement the safety learning that takes place during psychotherapy sessions that involve exposure therapy,” said UT Austin psychology professor Jasper Smits, who led the latest study in this line of research, which appeared in JAMA Network Open in June. “The question is can we tailor this approach to be more effective for each patient?”

When paired with exposure therapy — which aims to correct anxiety responses by offering safe spaces for patients to engage with their fears — DCS acts as a “cognitive enhancer,” promoting strong neural connections that help augment the learning experience.

“This two-part approach aims to enhance the exposure and create a memory of safety that sticks,” said Smits, who also directs the UT Anxiety & Stress Clinic.

Smits and his research team set out to refine the approach in a randomized clinical trial on social anxiety. They postulated that DCS would be more effective if it were only administered after sessions marked by “safety learning,” which they defined as evidencing low fear at the end of the exposure therapy session. But the strategy did not work.

Instead, the researchers found that the medication worked better as a blanket strategy, administrated before or after any therapy session. This confirmed the results of prior studies and emphasized new opportunities for exploration in the treatment of fear and anxiety disorders.

“The findings show again that this medication helps improve the outcomes of exposure-based therapy, adding to the evidence base for this,” Smits said. “There undoubtedly are individual and session characteristics that influence the effectiveness of this augmentation strategy, which is an important area for future research.”