In 1981, Barbara Mandrell had a No. 1 hit with “I Was Country When Country Wasn’t Cool.” If we replace “country” with “online,” it could be sung today by professor Sam Gosling, a pioneer of interactive and online learning.

As the university moves thousands of its classes online in the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, does he feel a little like a prophet whose prophecy has been fulfilled? “I’m not a prophet, because to be a prophet you have to predict something that’s not obvious,” he says. “Only a madman wouldn’t think that education wouldn’t look something like what we’re doing now. We felt, it’s coming — let’s get on with it, learn about it, and figure out how to make this work well.”

What Gosling, a Distinguished Teaching Professor and 21-year faculty veteran, has learned during his experimentation has never been more relevant, as students, parents and faculty members reluctantly enter the brave new world of online education under chaotic circumstances. Meanwhile, many wonder whether online college really can deliver a first-class education.

Of Computers and Classrooms

As social media really took off just more than a decade ago (Facebook topped 100 million users in 2008), teachers faced a problem: students bringing their laptops to class. Were they taking notes or were they surfing and posting?

But for UT psychology professors Sam Gosling and Jamie Pennebaker, who co-taught huge introductory courses in psychology and always had loved experimenting with technology, there was no dilemma at all. “We required laptops,” says British-born Gosling. “For those who couldn’t afford one, we had iPads they could borrow to get online.”

Getting students in the classroom simultaneously online allowed Gosling and Pennebaker to innovate at a feverish pace. They established chat rooms so students could better connect with one another, suddenly creating small communities within what had been a sea of anonymous strangers. They also had students take online surveys.

But soon the professors would be teaching students who were never in their classroom. In 2012, the term MOOC entered the higher education vernacular. It stands for “massive open online course,” and top universities were rushing to partner with educational technology companies such as Coursera, Udacity and Blackboard to get in on the ground floor of the MOOC movement. The University of Texas System, the largest early adopter, contracted with the non-profit edX.

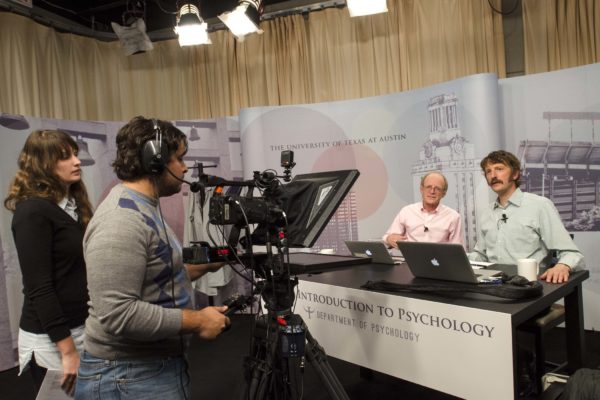

The next year, Gosling and Pennebaker made national headlines when they launched the world’s first synchronous massive online course, or SMOC, “Introduction to Psychology.” (Gosling now co-teaches the course with Paige Harden.)

As the technological “tinkering,” as Gosling calls it, became more intense, they soon faced a fundamental question: Were they filming a class or were they essentially producing a TV show? The filming-a-class model was how they started, teaching a class with two or three cameras. They addressed the students in the room, and the people not in the room felt they were looking in on someone else’s class.

When they began experimenting with the TV show approach, they looked into the camera, and students who were in the room, with a camera sometimes blocking their view, understood themselves to be the studio audience. That model quickly won out.

The shift in approach has a parallel in early cinema. “Many early movies were essentially the filming of plays,” Gosling says. “Then they realized, ‘Wait a minute — if we don’t need to have an audience, that means we can do things like move the camera, have close-ups and have special effects.” The result was a new art form that in many ways was more engaging.

Gosling calls this is an important lesson for teachers across the world who are moving to online. “It isn’t just taking a class and putting it online. You might have had to do that when you had two weeks to get things ready over spring break. But if you really want to do this, you need to unthink that, and say, ‘All right, if I were starting with the idea of having an online class, what would the class look like?’ It wouldn’t look like a film of an old-fashioned class.”

It’s clear that the media environment in which students have grown up influences and is itself the evidence of the ways they prefer to learn. YouTube-accessible documentaries have replaced the in-class film reel, and YouTube’s homemade videos have replaced everything from the math tutor to the instruction manual for the most obscure kitchen appliance. The 10- to 20-minute TED Talk is now the gold standard for lectures.

“Let’s face it — traditional teaching is not even medieval; it’s ancient!” Gosling says. “Plato standing in front of people saying stuff and people writing it down — we’ve been doing that for two and a half thousand years!”

Gosling experienced a lot of resistance when he started integrating tech into classes, but not from students. It came mainly from other faculty members and parents. Why? Because it did not look like Plato. But less than a decade later, people don’t see it as a strange way to learn at all. “Just as we are learning now with COVID, as so many are working from home, work can look different, and it can be OK. And in some ways it can be better. We were never trying to make a cut-rate version of education. We were asking, ‘Can we do it better this way?’”

The Student-Teacher Connection

Gosling recalls that in the beginning, many were concerned — “very reasonably” — that with SMOCs, teachers and students would be disconnected. But it turned out to be just the opposite. “People feel they know us like they know their favorite chat show host, because we are looking at them in the eye, and they feel in a way that they have a relationship with us.”

When universities began enlarging classes in the last century to achieve economies of scale, introductory courses in particular became Orwellian auditorium experiences, and any personal connection to the teacher was lost for all but the most outgoing students, those sitting down in front, raising their hands and frequenting office hours. So ironically, the futuristic technology students and teachers now must use might be returning education to an earlier, more classical psychological space. “The online class experience is you and them; it is more like a one-on-one tutorial in a way.”

Then too, the screen has the power to turn charismatic professors into celebrities. “This had never happened to us before, but Jamie and I would be stopped on campus by our students. ‘Hey it’s you! I can’t believe it’s you!’ They’d want to take photographs with us,” Gosling remembers. “They feel they have a relationship with you because this medium allows them to establish that.”

The Student-Student Connection

There are dangers, though. While online classes make it easier for students to establish a relationship with their teachers, they can make it harder for students to establish relationships with one another. “A lot of our tinkering was about trying to make people feel part of a community. What is the best size chat group? Do you want it to be two people or 10 people? Should it be the same people every time? Should it be different people every time? Should there be someone leading the chat group? There is so much experimenting to do.”

He found that five to seven people was optimal for chat group sizes. He also found it critical to assign a student to lead and moderate the chat and to have that role rotate. Leading discussions becomes part of learning. At the end of the chat, everyone rates the session and its leader. At the end of the semester, students are told how classmates rated them as a leader and are asked to reflect on their leadership experiences and what they think makes a good leader.

Of course, a sample size of five students can result in a dud of a chat group. “Sometimes a student can just get into a bad group — people who don’t want to contribute or who are hostile,” Gosling says. On the other hand, scrambling the chat group after every meeting would not allow students to build relationships or any sense of community. The solution was to form three chat group configurations and have students rotate through them so they see familiar faces on a regular basis but all of their eggs are not in one basket.

While most faculty members have to balance teaching and research, Gosling’s class is his research. “There are two really robust findings in educational psychology, and they are completely unsurprising: If students are made to work hard they don’t like it so much, but they learn much more.” One finding from Gosling’s own research is that one predictor of grades in his class is engagement, and they measure that through clicks. “We can see how much students click on the readings and click on the various things we tell them to do, and we take that as a measurement of how engaged they are. Every word they type, every mouse movement they make and thing they click on is recorded, and we can learn from that.”

Where Do We Go From Here?

For many, the term “online education” conjures for-profit online universities that advertise on TV. So if UT is largely online, for the moment, what is the special ingredient that makes a UT education worth it? “It’s really the difficulty and the complexity of it,” Gosling says. “The courses we’re teaching are more difficult.”

Related to that complexity is UT’s distinction as a top research university. “Most of the intro class is a broad overview, but then we can have a deep dive with somebody in the department who students might then go and take a course with or work in their lab in the years to come. That’s really what distinguishes the UT experience. Let’s face it — people are hired because they’re good researchers, so take advantage of that!” he tells students. “Take advantage of the fact that you have the world’s top researchers here. Go get involved with research. Go join a lab. Go get that type of mentorship experience. You have to seek it out. It’s not going to come to you.”

Even absent COVID-19, he sees an important role for online education, one that dovetails with the concurrent unrest over social inequality. “It’s an incredible privilege to be able to take four years out of your life to go to college. Think about the people who have to work jobs, who have to look after families, or who have to be distant. I could see a completely new model where you have residential halls scattered all over Texas, all over the world — you know, UT Namibia. They’re getting their lectures online all over the world, but then they’re discussing them with each other with the help of an in-person tutor.”

So will we ever return to in-person-only instruction? Gosling says, yes, at least for some classes. “But I do hope this challenging time and the changes to education it has necessitated has dissolved some of the distrust toward online classes and has demonstrated how they offer some important benefits to both students and faculty.”

Tips for Students

Gosling has a few important tips for students entering a world dominated, at least for the moment, by online classes.

Eliminate Distractions. Put your phone away. “We absolutely know from studies that even if your phone is switched off and on the table next to you, it just being in your peripheral vision is enough to distract you. If you are at home take your phone and leave it in another room. You do not need to be texting people.”

Likewise, if you’re on a desktop close Twitter, Facebook or whatever else you might have open.

Get Engaged. “Ask yourself why you are here,” he says. “You don’t have to be here. You didn’t have to go to university. You didn’t have to go to UT, but you did, so do it properly, and that means engage.”

He says he applies the same lesson to himself. “There are times when I’m doing all of these chores — the admin work, the research — and I’m just trying to get the things done. What I’ve learned is that it’s much more pleasurable, and I do it much better, if I just make a mental decision to do this and do it properly, to really engage with it.”

And don’t think you are engaged just because you have taken notes. “Writing something down is not the same as learning it,” he says. “Even worse is highlighting. Students somehow think it’s some magical process where if you highlight a sentence the knowledge goes up the highlighter, up your arm and into your brain. It doesn’t do that!” he says with a laugh.

“There has to be active engagement. Ask yourself questions. When someone’s lecturing, ask: ‘How does that apply to my life? What would be another case of that?’ Be sure you’re actively and critically engaged, not just listening, but thinking about it. ‘Wait a minute — that doesn’t make sense. A few minutes ago they said something that sounded like the opposite!’”

In the online world, that might mean not taking notes the first time you watch something — just listening and thinking about it — and maybe taking notes the second time.

Tips for Teachers

Gosling acknowledges the incredible amount of work it takes to create an online course from the ground up. Here are a few ideas to improve teaching in this new world.

Break It Up. His first piece of advice for members of the faculty is to think in terms of smaller modules that can be put together in different ways. “Don’t lecture for more than seven or eight minutes. Break it up. Give them some kind of survey or show a video or do a demonstration. Really think about all the different things you can do and break them up into parts.”

“Next year if you have to redo your course, you can say, maybe this module goes with another lecture.”

One of the most effective segments in his class is “In the Experts Chair,” in which another faculty member in the department makes a guest appearance and Gosling and Harden interview them. These interviews might be as short as 10 minutes.

Frequent Testing. Another finding that comes from their research is the importance of frequent testing. “In our class, we have a high-stakes test at the beginning of every single class that counts toward the final grade, because it’s incredibly important to get feedback on what you know and what you don’t. This is one of the great advantages of an online class. In an in-person class of 500 students, there is no way to test all the students every class, mark all of their papers, and give them their grade back right away. But if we can do it through the computer, that means students every week learn how much they know and don’t know.

“The obvious benefit of this is that when you think you know something but you don’t know it, you can concentrate on that. The other benefit is when you really know something very well, there’s no point in studying it for another hour. You want to be well calibrated.”

Gosling says that without frequent testing, students, especially freshmen, often will flub their first test, three or four weeks into a course, but write it off as a fluke since they did so well in high school. If they then flub their midterm, now it’s too late to dig out of that hole. “In our course, if you do badly on a test in your second-ever class, you might say that was a fluke, but then three days later you have another test and do badly. By the third class you know that you need to adapt, to go see the professor or TA. Frequent testing does not permit students to be deluded about their performance.”