In November 2019, Jennifer Harrison met with her associate director of occupational and lab safety for a monthly clinical safety meeting. As part of a routine check, she was asked whether the UT Health Austin clinics were stockpiled with enough N95 masks and personal protective equipment. Harrison, senior director of clinical operations at UT Health Austin, the clinical practice of Dell Medical School, says she laughed a little and asked, “Why?” Harrison, and countless health care workers around the world, had no idea that the upcoming months would bring a pandemic with a massive death toll.

“I’ve been a nurse for 18 years,” Harrison says. “I’ve never had to prepare like this.”

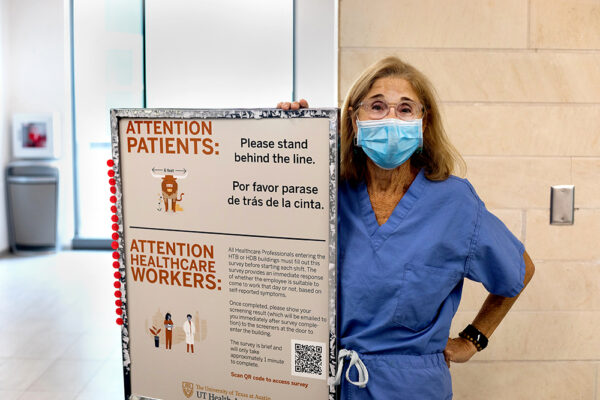

For health care workers at The University of Texas, working during the age of COVID-19 has brought many challenges. COVID-19 cases began showing up in Austin during March, requiring massive preparation on all fronts.

“In the first few weeks it was very hectic for all of us because the scope of the challenges and actions needed was much bigger than I had ever seen,” infectious disease specialist Dr. Rama Thyagarajan says. “I have worked on and overseen many outbreaks, but not to this scale.”

Harrison was one of the first people to begin testing for COVID-19 on campus, on March 11, partly because “nobody wanted to do it,” she says. Dr. Amy Young, chief clinical officer at UT Health Austin, was Harrison’s testing partner for the day. Young decided to test their first subject from the patient’s car in a parking garage. Their second patient was tested inside the clinic, and wearing masks was not yet standard.

“I told them, ‘We’re not doing that again. That just put you and I and everyone we walked in the hallway by at risk,’” Harrison says. “We realized very quickly that we didn’t exactly know what we were dealing with.”

The next day, March 12, Young and Harrison had a drive-thru testing clinic set up to serve the community.

“I got a call at 5 in the morning that said, ‘Yep. It’s real. We need to get going,’” Harrison says. “So, we did it. That’s when we realized very quickly that with COVID we needed to take some extra precautions. It was scarier than we all thought.”

Harrison says that after she came into contact with patients, she immediately felt a heightened awareness for everything she touched.

“That’s when you’re like, ‘Oh, what risks have I been taking?’” Harrison says. “And you have those conversations, because my husband and children were healthy and they weren’t going anywhere. I was the risk. So, it gets very real with the thought of, could I bring this home to them?”

I’ve been a nurse for 18 years. I’ve never had to prepare like this.

Dealing firsthand with COVID-19 patients made Harrison and Young realize the importance of communicating with and educating staff members at the clinic to keep them and their families as safe as possible. As an infection prevention expert, Thyagarajan was able to reassure students, trainees, providers and staff members by constantly sharing new COVID-19 information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization as it developed.

“There was a lot of education to our staff regarding appropriate PPE use, taking equipment on and off, how to make sure they’re safe when they go home and helping them feel comfortable and at ease so that if we follow these practices, we won’t take this virus home to our families,” Harrison says.

When leading health care workers through a time when their lives could be on the line, Harrison says that she tried to accommodate colleagues’ circumstances at home and was upfront about the risks of this uncharted territory.

“You have to think about what you’re going through, what they’re going through, and then talk them through what the fears are and how we can support each other through it in order to really be able to work together on how we can come together and serve the community,” Harrison says.

When the clinic started testing in March, there was a shortage of test kits and protective equipment. Each day, staff members would count how many tests, gowns, face shields and masks they had left.

“We were very concerned,” Harrison says. “For the first three weeks we could have shut down any day if we didn’t have the right equipment. That’s when the donations started coming in.”

Members of the community donated gloves and masks. Tito’s Handmade Vodka donated hand sanitizer. Clinical Pathology Laboratories, which processes the tests, eventually increased the amount of test kits the clinic received.

Young got a tip that the transport containers that gynecologists use to collect genital cultures could also be used for the first COVID-19 tests. Young, an OB-GYN, immediately called gynecologists across Austin, asking whether they could donate supplies, and she spent the day driving to each clinic.

“The sense of collaboration and cooperation was really incredible and enormous,” Young says. “There was resourcefulness. I never thought about how tired I was.”

At the same time, other medical care had to continue. Zoom was the platform selected to expand UT Health Austin’s telehealth capabilities, keeping patients safe by allowing them to stay home. Telehealth was activated by an IT team during a weekend in March, and the clinic shifted to 80% virtual appointments, Young says.

“That was a huge effort to shift very quickly to,” Harrison says. “From no one having experience using Zoom in a patient environment to people quickly becoming experts and teaching the patients how to do it in order to get on the platform was awesome.”

At the peak of COVID-19 cases in Texas during the summer, Harrison says the drive-

thru clinic was testing about 120 people a day. For the fall 2020 semester, the clinic primarily has tested faculty and staff members but also has served as backup to University Health Services, the main testing site on campus for students.

While many others quarantined at home, health care workers remained on the front lines, continuing their regular work of caring for others while taking on the added burdens posed by the pandemic.

“When you have a large volume of cases and an evolving pandemic with a flooding of new information … it’s difficult to adjust to it,” Thyagarajan, who is also an assistant professor of internal medicine at Dell Medical School, says. “All of us had to do our regular job and then the added COVID planning and work because the hospital or clinic is not at a standstill, and patients still need care for their non-COVID health issues.”