Nearly every Friday in the late afternoon, a group of researchers comes together in a virtual room on Zoom. One by one, they join the meeting, greet one another and ask how the day is going, but soon enough they get down to business. They are united by a common goal — to study and mitigate the effects of COVID-19.

The group is led by Andrew Ellington, professor of molecular biosciences, founder of the Ellington Lab and holder of the Wilson M. and Kathryn Fraser Research Professorship in Biochemistry at The University of Texas at Austin. The group also consists of invited campus molecular biosciences experts, such as Christopher Sullivan and Adrian Keatinge-Clay, and perhaps surprisingly, includes a whole cohort of various undergraduate researchers. Here, they discuss their findings for the week, and members receive constructive feedback about their working scientific theories.

Right now, many students dream of being back in faculty labs and doing hands-on research on campus, but while UT determines a safe and effective way for students to fill labs again, professors, including Ellington, have found creative ways to engage and educate student researchers.

“What is the difference between an undergraduate and a graduate student?” Ellington asked. “The answer is three months (between graduating and starting graduate school),” he said jokingly. “The brains, drive and individuals themselves are pretty much the same — I just get the great benefit of working with them early.”

The Ellington Lab focuses on research in synthetic biology, protein engineering and DNA nanotechnology. Some of the undergraduate students working with Ellington have formed a small team, dubbed an Inventors Team or iTeam. These students come from the College of Natural Sciences’ Inventors Program and the Freshmen Research Initiative, and they are more than ready to apply their skills in research and design. Today, this particular iTeam is researching natural therapeutics — compounds and molecules usually from plant products — in hopes of either alleviating the risk of COVID-19 transmission or tackling one of its many symptoms and side effects.

With top pharmaceutical companies and research experts around the world scrambling to create a viable vaccine, the Natural Therapeutics iTeam wants to tackle the problem in a completely different way: They want to create an antiviral treatment. Antivirals are drugs used to treat patients who have become sick, and vaccines are used to prevent diseases in those who are still healthy. So, essentially, this group is on the defense against COVID-19.

In approaching this problem you just have to have different angles — it’s almost like a game — and solving it’s the fun part.

Mbolle Ekane is one of these students. She is a cell and molecular biology senior who has been working with Ellington since 2017. Ekane described how the lab is focusing on the many unexplored approaches to mitigating COVID-19. Her project in particular explores the overreaction of the immune system to the virus.

“Basically, when you first get infected, your immune system’s like, ‘Hey, let’s go fight this,’” Ekane explained.

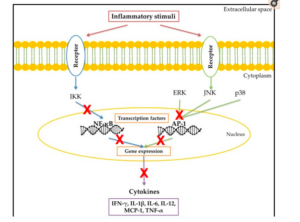

This immune response can be positive, but with COVID-19 it can also cause complications called a cytokine storm. This occurs when the body’s immune response goes into overdrive and starts to attack its own cells and tissues, and not just the virus.

“What it does is release these cytokines to try and fight the virus. However, the virus essentially takes over that mechanism, and it becomes a negative feedback loop where you’re overexpressing those cytokines — your body ends up damaging more cells than you’re actually helping,” Ekane said.

What’s most significant about cytokine storms is their correlation with patient deaths from COVID-19. Studies from Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy and Frontiers in Immunology show that decreasing this over-response is beneficial for patients, and Ekane’s work supports the idea that breaking down this response with some sort of therapeutic could aid COVID-19 patients.

Ekane is researching the potential of quercetin, a naturally occurring product found in buckwheat and other plants, such as onions.

Meanwhile, iTeam member Nicole Garza, a junior human biology major, is investigating a completely different approach to fighting COVID-19. She is looking into therapeutic compounds that can stop the virus from attaching to the host. Right now, her focus is on emodin, a natural compound found in rhubarb and buckthorn and used in traditional Chinese medicines.

Since the beginning of the semester, the students have spent hours each week surveying the literature and exploring other compounds in search of approaches that block or mitigate the virus.

“We share a vast article base, and Dr. Ellington brings top colleagues to our research meetings, where we are sort of poked and prodded,” Garza said. “It’s like, ‘OK, what can you do here? Have you thought of this? How is this going to work?’” Laughing, she said, “Maybe poked and prodded aren’t the right words, but these thought-provoking questions are sort of the idea of research in itself.”

This research area of natural therapeutics for COVID-19 is largely unexplored, and Ekane said that the work has been rewarding and challenging. “As a future scientist, it’s crucial,” she said. “In approaching this problem you just have to have different angles — it’s almost like a game — and solving it’s the fun part.”

This is definitely opening a whole new door of interest for me as I proceed with my degree.

In addition to finding these therapeutics and studying their effectiveness for various ways to mitigate the virus, the team is also investigating methods in which it can mass-produce solution products for testing and possibly even distribution. These involve researching the biosynthesis pathways of the compounds — the ways and steps in which simpler biochemical compounds combine to create that end product. Understanding pathways is crucial because it provides a better idea of how to improve production to yield more product.

This whole process is complex and involves studying a therapeutic compound’s genome, digging into what sorts of plasmids or vectors — certain types of bacteria — the team can use to help produce the product. It also involves researching ways to extract and purify the compound for further investigation.

Though they may not be returning to lab in person until next spring, Ekane and Garza are excited and hopeful for the future.

“This is definitely opening a whole new door of interest for me as I proceed with my degree,” Garza said.

“It’s great because right now I don’t feel like I’m doing nothing,” Ekane added. “I feel like I’m doing my part in the world of a scientist, trying to figure things out to help millions of people all around the world.”