On the night of his historic election in Georgia, the Rev. Raphael Warnock talked about his mother, saying her “80-year-old hands that used to pick somebody else’s cotton went to the polls and picked her youngest son to be a United States Senator.” He was referencing a slogan used by the civil rights organizers in the 1960s and ’70s to mobilize a newly enfranchised Southern Black electorate to exercise their right to vote. Their slogan was “hands that pick cotton now can pick our public officials.”

Forty years ago, we made a film about the first post-civil rights attempts of Black people to win political office in the deep South. One of the places I visited looking for stories was the rural majority-Black counties in southwest Georgia.

I remember driving to tiny Fort Gaines on the Chattahoochee River on the Alabama border, where a Tuskegee Institute professor, an old friend, had grown up. I called him from the one pay phone on the town’s main street, watching a dog sleeping in the middle of the road, not moving throughout the call because there wasn’t any traffic.

There also was not much political activity back then. Nothing really to film. What a difference the decades have made. Black turnout in those rural counties in Georgia was significantly higher than in white conservative counties, fueling the Democratic sweep of the runoffs.

It’s hard to explain what it was like for Black people to run for office in the rural deep South back then. Looking back at our film “Hands That Picked Cotton,” about the early grassroots electoral organizing, is like looking at an alternative political universe.

We followed Bob Clark, the first Black person elected to a state Legislature from the rural South since Reconstruction, running for Congress. His challenge was getting out the Black vote in a Black-majority Mississippi Delta district.

Generations of poor Black people — fearful, intimidated by past violence and legally sanctioned oppression, and with no experience of participating — were reluctant to register, let alone vote. One day, Ed Brown, the younger brother of 1960s firebrand H. Rap Brown and Clark’s campaign manager, drove with us around the district.

On camera, Brown pointed at a courthouse up on a hill where the county’s single polling site was, telling us that getting people to register and vote was one giant step, like walking from one century to the next century. That November, the turnout was low and Clark lost. But the organizing continued, and a few years later, a Black challenger took the seat.

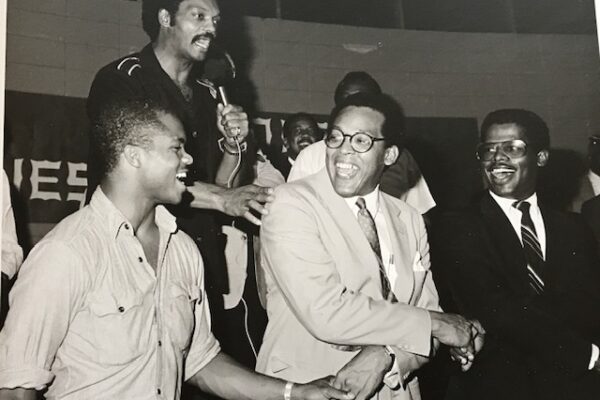

We also followed candidates for a county commission in Black-majority Humphreys County, Mississippi, the self-proclaimed catfish capital of the world. The stakes were control of the county government. In the Delta, those first electoral pioneers, candidates and volunteers — mostly public school teachers and small farmers who risked losing their credit at local banks — were on their own. We were the only camera crew anywhere near the local elections throughout the hot summer in 1983. Filming those people was an inspiration, a testament to their bravery and their belief in the power of democracy.

And that election night, far from any nightly news coverage, they won.

Today, there are thousands of elected officials in the South who are from minority communities. Where most Blacks were once barred from voting by poll taxes, literacy tests, unchecked violence and the refusal of officials to register them, it is a different country and a different South. Tim Scott of South Carolina, a Black conservative Republican, was elected to a Senate seat once held by the rabid racist Benjamin Tillman, known as “Pitchfork Ben.” Warnock will hold the seat once held by another staunch segregationist, Herman Talmadge. And those same voters who elected Warnock also elected Jon Ossoff, a 33-year-old liberal Jew, to Georgia’s other Senate seat. Ossoff is the youngest person elected to the Senate since a 29-year-old in 1972, Joe Biden.

The occupation of our Capitol in Washington, D.C., by a mob is a dark mark for our country. But we should not forget the election of the previous day. In this Georgia runoff, those Black hands truly made a historic difference.

Paul Stekler is documentary filmmaker and a professor of public affairs and radio-television-film at The University of Texas at Austin.

A version of this op-ed appeared in USA Today.