Yes, there was a global pandemic that disrupted every part of the university for more than a year. Yes, there was a historic freeze in February that shut down the state of Texas. But the real question on everyone’s mind is, how is Domino?

In early June, on one of my first days back in the office, I went to see for myself. I exited the Main Building and crossed the cul-de-sac to the West Mall. Just to my right, at the southeast corner of the Flawn Academic Center, was the patch of grass walled in by hedges that had long been the cat’s domain.

I could not remember just when I started noticing Domino, but it had been time out of mind, at least the better part of a decade. I had noted with amusement how, as time went on, the feral cat seemed to have become ever more provided for, dare I say spoiled — another bowl for food or water, another kitty shelter appearing seemingly with each passing season. Surely it was the most luxurious life a feral animal ever led. Among all creatures on Earth, Domino had lucked into the optimal existence: complete freedom and complete care. Through nothing but laziness and vagrancy, he had it all.

Occasionally I would spot someone approaching Domino to stroke the black-and-white fur that inspired his name, and then empty a plastic baggie or Tupperware container of cat food into one of his several bowls.

At first on this day, I didn’t see him at all. I saw plenty of evidence of him — the empty plastic bowls and two cat shelters, but no Domino. Someone called my name, and I turned to visit quickly with a passing colleague, and when I turned back around to face Flawn, there he was. He had been there all along, sprawled on his side under the brushy hedges, blending so well with the dappled noontime light I had missed him. He was lying so still I watched his sides for a few long moments to make sure he was breathing, before I entered his domain.

I stepped through the narrow opening in the hedge and crossed the patch of St. Augustine slowly. He raised his head, his sea-foam-green eyes squinting at this stranger, then laid his head back on the dirt: “Oh, no food? Just my public. Sigh. Have them wait in the foyer.”

Just then, a woman appeared with her own lunch in one bag and cat food in another. Taslima Haque, a Ph.D. student in plant biology, was one of Domino’s stalwart caregivers, having been in rotation for the past five years. With biological research experiments to constantly tend, she was one of those people who never left the campus during the pandemic. Day after day, she would mask up and dutifully hike to her lab in the Hackerman Building, and on her way, no matter what the weather, she would feed Domino.

“I have been a cat lover since my childhood, and I had several cats back at home at that time,” she told me. Half a decade ago, when she came here for grad school, she says, “One of my friends was discussing campus cats, which intrigued me, and I decided to pay Domino a visit.” Initially, he was wary, she recalls. “Domino is a classic cat character. He took a little time to come close to me when I started feeding him.”

In my naivete, I had just assumed that good-hearted campus staffers simply brought him food whenever the spirit moved them or whenever they were scheduled to be on campus — but no. Domino has a highly coordinated support network.

That network of care operates with the blessing and full support of Animal Make Safe, a program within UT’s Environmental Health and Safety office, a unit within Financial & Administrative Services. Carin Peterson directs Animal Make Safe, and Carin’s group is who you call when your campus visitors include raccoons, bats, or anything else that needs to find its way back to nature. Carin is also the contact for the Campus Cat Coalition, which is affiliated with the Austin Humane Society, Austin Animal Center, Alley Cat Allies and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

I soon learned the abbreviation TNR, which stands for “trap, neuter (or spay), and release,” the enlightened strategy for compassionately caring for these majestic beasts without allowing the campus and adjacent neighborhoods to become overrun with hundreds of hungry cats.

I also learned the difference between a stray animal and a feral one: a stray used to be someone’s pet and decided life on the road was more its cup of tea. A feral animal, by contrast, was born and had always lived apart from humans, Domino being Exhibit A.

What’s more, there is not just one feral cat on campus, but as you might expect in an area of almost 500 acres, there are many.

Naturally, I wanted to know how many and where they were, but Carin told me “the cat people” on campus do not appreciate publicity of specific cats and their locations “due to past negative actions against the campus cats.” Some report 40 cats that receive coordinated care on campus. That’s about 1 per every 10 acres. Mice, beware.

I found a Facebook page called Cats of West Campus, a group founded by Christina Huizar, which features non-location-specific updates on cats both on campus and in the West Campus neighborhood. There, I saw updates on Mini, so named because she was found as a kitten near Domino, making her his Mini-Me. So even though Domino’s ear is clipped, a sign that a feral cat has been vaccinated and neutered or spayed, perhaps he found romance before the Cats of West Campus folks found him.

Having always been a dog person, I knew little about cats, but I learned that Domino is a “tuxedo,” which is not a breed but rather a coat type that can appear in various breeds, like a calico or a tabby or a brindle. Owners of tuxedos, or “tuxies,” have described them as twice as smart as other cats, which could explain Domino’s remarkable success. Learning that Shakespeare, Beethoven and Sir Isaac Newton all owned tuxedo cats, I deduced that Domino naturally preferred the brainy setting of a university.

Besides Mini, I saw pictures of other tuxedos including George, Sonny, Stevie, Sister (also known as Lil Miss Sassy Boots) and Signature Tux, so named because he was found near the Signature 1909 apartments on Rio Grande Street. There was Siam and another Siamese named Blue. There was Ghost. There were solid black cats named Nox, Nova, Midnight and Jasper, along with Chadwick and Sombra, said to be the nephew and niece of Domino from back in his virile days. All-black Sergei and Bushka are also said to be nieces of Domino

(despite Sergei being a masculine name), though one wonders if this genealogy is known or simply a way of leveraging Domino’s popularity to get the cats adopted, the post reading, “Domino’s nieces looking for a home.”

Domino might have a “classic cat” personality, as Taslima said, but he is not a loner. On more than a few occasions over the past decade, as I made my way up the sloping West Mall to the tune of “Texas, Our Texas” ringing out over the campus at 8 a.m., I noted another quadruped of similar size hanging out under the shrubs that line the concrete wall at Flawn’s base. It was an opossum. It did not seem right to me that one denizen of campus should have a name and his roommate should not, and so I called the opossum Otis. The Lord did not bless Otis — or any opossum — with the charisma of a pet; otherwise the dead-eyed, bare-tailed marsupials would have become domesticated. Nonetheless, Domino passively shares his good fortune with Otis once he has eaten his fill. Other caretakers feed Domino out of their hands instead of leaving food in bowls, so raccoons, who are a good bit more vicious than opossums despite being cuter, don’t get too used to the meal plan.

Learning that Shakespeare, Beethoven and Sir Isaac Newton all owned tuxedo cats, I deduced that Domino naturally preferred the brainy setting of a university.

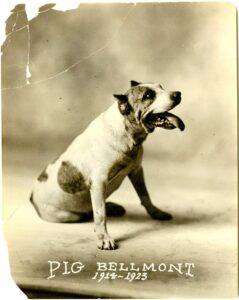

UT history buffs recognize our fascination with Domino as being a strong echo from the early 20th century. In 1914, the campus fell in love with a pit bull named Pig Bellmont. Though Pig belonged to Athletics Director Theo Bellmont, and was brought to Austin from Houston as a puppy, he much preferred to roam the campus freely, greeting students more enthusiastically than Domino would ever dream to.

Writes my old friend Jim Nicar: “Each morning, Pig greeted students and faculty on his daily rounds. He frequented classrooms, and on cold days was permitted to visit the library (now Battle Hall). Pig regularly attended home and out-of-town athletic events, and it was said he would snarl at the slightest mention of Texas A&M.”

Not only is Domino merely one among a number of cats, but there are also several other species that have attracted the care of humans. My colleague Marsha Miller, who as UT’s longtime principal photographer knows the campus better than just about anyone, told me of a professor who feeds the pigeons outside the Physics, Math and Astronomy Building every day. They know him on sight and flock to him before he ever breaks out the seed.

A stone’s throw from Domino’s home is the more famous Turtle Pond. There, during the spring when the turtles are moving back and forth between the pond and various nesting areas, students can be spotted picking up the red-eared sliders and moving them off Inner Campus Drive and out of harm’s way. (Public service announcement: Always move the turtles in the direction they’re traveling; they’re going that way for a reason.)

And let’s not forget Tower Girl, the peregrine falcon — or falcons — who intermittently live atop the Tower, nesting in a box provided and maintained by UT’s Biodiversity Center and enjoying the best view in Central Texas. Clearly there is something in many of us, whether acting in an official or unofficial capacity, that enjoys caring for these creatures. And those of us not actively engaged in caring for them are nevertheless enriched by the animals’ presence among our daily routines. I even like seeing Otis.

After the life-threatening, weeklong freeze in February, one of Domino’s feeders, natural sciences professor Al Mackrell, recounted to journalism senior Ashley Miznazi of Reporting Texas TV that when the snow melted away, Domino was the last cat to emerge. “He had to make a dramatic entrance,” Mackrell remembered, adding, “I think a bunch of us ugly-cried when we realized he was OK.”

As with all institutions, as Domino is, there is a system in place to provide for him, even in the lean times, even in the cold. In that, I suppose he is a powerful metaphor for the university itself and all of its pillars of support. And as we celebrate Domino’s survival, we can celebrate our own, too.