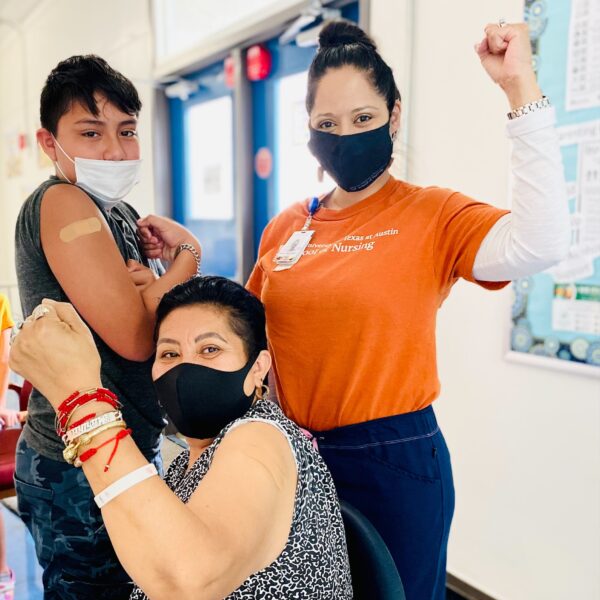

On a recent hot afternoon, residents of an Austin-area apartment complex are slowly driving through the parking lot with windows rolled down so a team of UT Austin School of Nursing faculty and students and other volunteers can administer the COVID-19 vaccine into the proffered arms.

One of the team is Janice Hernandez, a Nursing School clinical assistant professor, who chats in Spanish with the drivers, answering questions and explaining how the vaccine works. Other afternoons you can find her at the Corazon Latino Dance Studio or on Wednesdays at the First Spanish Seventh-day Adventist Church on Rundberg Lane near Georgian Drive providing injections as people pick up food at the church’s weekly food bank.

Hernandez is part of an innovative UT Austin and community partnership known as Vaccination Administration Mobile Operations (VAMOS), a mobile clinic set up at various Austin-area churches and community sites to reach out to hard-to-reach Austinites in largely underserved communities and to ensure that they have access to the vaccine.

“As a Latina, a Spanish speaker and an advocate for the Latinx community, it was not difficult to come right in and communicate with people at the VAMOS sites,” she said. “Many people coming to the mobile clinics have a lot of questions regarding the vaccine, and having someone who speaks Spanish and who can understand and listen to their concerns is very reassuring and comforting to them.”

VAMOS, along with Vaccinate, No Waste (VaxNow), in which doses of the vaccine prepared in excess of scheduled appointments are taken to individuals who are homebound or have difficulty accessing vaccination appointments, was launched in March 2021, when it became apparent that the UT Austin vaccine clinic on campus would not be able to provide vaccinations to the entire community.

Hernandez recognized that the mobile clinics would need more Spanish-speaking translators and volunteers to reach Latino communities, and she became one of the earliest volunteers. Designated a “site lead” for the mobile vaccination clinics, she manages a team of School of Nursing faculty and students, community health workers, and volunteers from Dell Medical School and the UT Medical Reserve Corps.

“These delivery models were set up to provide quick and nimble mobile vaccine clinics for small groups in the communities that need help the most,” said Stephanie Morgan, a professor of clinical nursing, who co-leads the UT Austin vaccination hub and mobile clinics. “They’re helping us make sure that residents of underserved communities who are most susceptible to the virus and the least likely to have access to the internet and transportation get vaccinated.”

Going to areas where people live, work and worship is key, Hernandez stressed.

“Holding the clinics in these areas builds trust and acceptance of the vaccine,” she said. “One of the biggest barriers in some communities is gaining access to health care, so being in the exact location where they live or congregate makes the vaccine much more accessible. For instance, the collaboration with the Spanish-speaking church’s mobile food pantry every Wednesday makes getting vaccinated so much easier.”

The success of the mobile clinics is based largely on a tailored outreach and a trusted and personalized registration experience as well as information, education and logistical convenience for people who can most benefit from the vaccine.

The success of the mobile clinics is based largely on a tailored outreach and a trusted and personalized registration experience as well as information, education and logistical convenience for people who can most benefit from the vaccine.

“Everyone on the team has a role,” Hernandez said. “There are educators providing information about the vaccine, mixers mixing the medication, vaccinators giving the injections, and check-in assistants filling out the documents and vaccination cards and explaining when to return for the second dose. We also have volunteers monitoring the vaccinated for a minimum of 15 minutes after the vaccination to ensure everyone is safe and that there are no adverse reactions.”

Often individuals in the community reach out to the School of Nursing requesting that a vaccine clinic be set up in an underserved area. As site lead, Hernandez submits a request to UT Health Austin and performs a site visit to determine a location for the vaccinations, the approximate number of vaccines needed and the number of team members to assist. She also ensures that the team has all the supplies and equipment needed for the event.

“As a nurse, specifically a Latina nurse, I identify with many of the same cultures, values and beliefs, which has helped me in this work with the Latinx community,” Hernandez said. “Being honest, transparent and empathetic about their concerns, fears and hesitancy in deciding to get the vaccination has made a significant difference. We focus on building trust through communication, such as providing education in simple words and terms that are clear and understandable. It’s equally important to listen, and I always clarify, ‘I am not here to tell you to get the vaccine or make you get the vaccine. I just want to educate you about the vaccine and answer any questions you may have so that you are able to make the best decision for you and your family,’ which usually helps them determine how to move forward.”

Many of the people she has spoken to at the mobile clinics obtain information about the virus and vaccine from social media or from people close to them, such as family, friends and community members.

“They hear the stories of being sick for days after receiving the vaccine, misinformation regarding how it works, or that if you have had the virus in the past, you don’t need the vaccine,” she said. “Now, with the delta variant hitting close to home and affecting many of their family members who chose not to get vaccinated, they are coming back and changing their minds. One man lost his father, another his brother, and one woman lost her mother and sister. I also believe that as they see more people getting vaccinated and are doing well with no side effects, they now trust they too will be OK after getting vaccinated.”

The service industry is another group that Hernandez recognizes as being at high risk of contracting the disease yet having the most difficulty obtaining the vaccine. Many of these workers have two or three jobs, get off their shift late at night and are unable to take time off during the day to get to a clinic for a vaccination. Some are also undocumented and afraid of being asked for documentation or an ID.

“So, this is where I come in,” she said. “The VAMOS clinics typically run from about 3 to 8:30 p.m. After that, any leftover vaccines must be disposed of, essentially wasted, if there is no one to give them to. I take the leftover doses to local restaurants and taco trucks and ask if anyone in the back kitchen or any of the front servers need the vaccine.

“For the Latinx community, the highest concerns are vaccine safety and accessibility, especially among the undocumented. As we continue these efforts to vaccinate the underserved communities of color and those most susceptible to the disease, the community sees our presence, and our presence increases credibility and trust.”