Genealogy is not a subject many middle school boys are into. But I was probably 13 when I started riding my bike to the McAllen Public Library, making my way back to the genealogy room, and digging at my roots. The sight of a 13-year-old boy in a Dallas Cowboys jersey at a library carrel on a Saturday morning surely caused many a white-haired lady in the stacks to clean her bead-chained glasses and look again.

The paper trail for my family tree reached fairly far back in several lines, and into the 1600s for the line that gave me my last name. When I reached the end of that trail, I put all my pedigree charts and photocopied records in a metal file cabinet, thankful for what I did know, and moved on to other pursuits.

Then the internet happened.

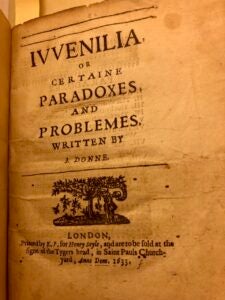

Now I had vast new areas in which to dig and tools more powerful than I ever could have imagined. One night just last year, while browsing genealogy sites on my phone from my recliner, I stumbled on a name I had never seen before. Apparently, he was my ninth-great-grandfather, Henry Seile. (I spell my name Seale, but back then it was a free-for-all — Seale, Seile, Sale, De La Salle.) The brief description said Henry had been a book publisher in London in the 1600s. More Googling turned up the titles of some of his books, which included a posthumous book by metaphysical poet John Donne and the very first book by political philosopher Thomas Hobbes. WorldCat, a sort of global card catalog, showed me where the books actually were.

Expecting to see names like Oxford and Harvard, I entered my ZIP code beside the “Find a Copy in the Library” field, and the first library listed was all of 200 yards from my office in the Tower, the Harry Ransom Center. These books — the very books Grandpa Hank published and probably even handled almost 400 years ago — had been sitting for years almost literally under my nose.

I had done a considerable amount of research at UT of my old Texas roots, at the Briscoe Center for American History, the Tarleton Law Library, and even the Perry-Castañeda Library, where I once napped as a student. But I had never even considered that the Harry Ransom Center could have any genealogical relevance.

I went to the Center’s website and clicked “Visit.” A straight-forward form asked for the titles I wanted to see, and later that day, I got an email from Kathryn Millan at the Reader and Viewer Services desk helping me set up my appointment.

I replied that I’d like to come in two days to see the books. “Also, if possible,” I wrote, “I’d love to visit with someone who knows a little about early-modern/17th century printing, even if it’s just the technical aspects – paper, ink, binding, etc. If there were someone on the staff in whose wheelhouse these books fall and with whom I could chat as I viewed them, that would be a huge bonus.”

She scheduled the visit, then promptly wrote again: “I forgot to let you know about our Early Books and Manuscripts curator, Aaron Pratt.”

Pratt, who earned a Ph.D. at Yale in 2016, wrote promptly: “So pleased that you’ll be visiting — and how very cool that you are related to Henry Seile, a 17th-c English bookseller/publisher whose output and career I know well. I am available Thursday afternoon at 2 p.m. How about I come find you in our second-floor reading room then? I should also note that we have a lot of books that were published or sold by Seile, ones well beyond those you’ve requested. Here’s a link to a catalog search that will show you all of the volumes we’ve cataloged under his name.”

When I reported to campus as a freshman in 1985, I had some vague awareness of the humanities research center that bore Harry Ransom’s name and anchored the southwest corner of campus like a huge fire-safe for some of Western civilization’s most valuable documents. After graduation and a stint back in my hometown, I returned to campus to write for UT’s alumni magazine and later for its president and the offices of marketing, news and development. And so I had been to the Ransom Center dozens of times for my work. My job after all was and is bragging about UT, and so a working knowledge of this and other campus gems is basic.

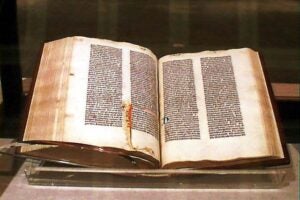

The basics at the HRC start with the Gutenberg Bible, one of just 20 complete and intact copies in the world, purchased in 1978 for $2.4 million. It was the first substantial book printed in Europe with movable type and therefore an emblem of one of the most important advances in the history of the West — and, eventually, the world. Another marquee holding displayed just a few feet away is the Niépce Heliograph of 1827, the earliest known surviving photograph produced with the camera obscura.

Beyond these, in the Center’s galleries, one finds exhibits both of visiting collections and those curated from its own archives. The Center has 42 million original manuscripts by heavyweights such as James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, Anne Sexton and Norman Mailer. It also holds the archives of actor Robert De Niro and filmmaker David Selznick and is home to the Watergate papers of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

Prefer pictures? It holds 5 million photographs and more than 100,000 works by artists such as Picasso, Matisse and Kahlo. And it’s not even UT’s main art museum! The Blanton Museum of Art holds that distinction.

UT has been collecting rare books since 1897, when Swante Palm donated most of his 12,000 volumes to the university, a gift that increased the size of our library by more than 60 percent.

But it really got up a head of steam when Harry Ransom, an English professor who eventually became UT’s president and the UT System’s chancellor, founded the Humanities Research Center in 1957. In 1956, Ransom signaled his ambitions in a speech to the Philosophical Society of Texas. He proposed “that there be established somewhere in Texas — let’s say in the capital city — a center of cultural compass, a research center to be the Bibliothéque Nationale of the only state that started out as an independent nation.” The Humanities Research Center was renamed the Harry Ransom Center after his death in 1976, conveniently maintaining the same initials.

UT’s acquisitions grew so rapidly that by 1964 The New York Times would write, “The university has been in recent years the largest buyer of rare books in the country and, some think, in the world.”

Dallas billionaire and future presidential candidate Ross Perot was in full agreement with the late chancellor’s aspiration, and in 1986, when a famous collection of 1,105 early English books and 250 manuscripts known as the Carl H. Pforzheimer Library came up for sale, Perot seized the collection for $15 million and delivered it to UT, which then raised the funds to pay him back over time. It was the largest purchase of a literary collection in history. Perot’s mission was to “use his wealth and influence to lift his beloved Texas, not long removed from the rugged frontier, to the upper echelons of western culture,” wrote David Maraniss of The Washington Post.

Among other things, the Pforzheimer collection includes the first work printed in English and original quartos and folios of Shakespeare. “This is one more step toward building the finest university in the world,” said Perot.

In a news conference on the fourth floor of the Flawn Academic Center hosted by President Bill Cunningham and including Gov. Mark White and Lt. Gov. Bill Hobby, Perot presented the collection to UT. Decherd Turner, then director of the HRC, called it “the major bibliographic acquisition of our time.”

At the presser, visiting British scholar Colin Franklin said, “The state of Texas, this university in particular, and this humanities research center is known to have created in a brief time such a library as has become the focal point of research for scholars in English literature,” adding that the Pforzheimer specimens were the best of almost every title. “Again and again, one is referred, rather irritatingly, to the Pforzheimer copy, as in some way better than one’s own.”

“Whether Texas in fact might be overreaching is a matter of dispute among rare-book experts and curators in this country and Europe,” Maraniss wrote in the Post. “Some librarians on the East Coast, while not commenting for the record, spoke with more than a hint of condescension about the manner in which Texas is trying to buy culture.” “They are not some kind of outlaw marauders,” Arthur Freeman, a rare book consultant, told Maraniss. “Their collections are so serious and so important, that adding to it isn’t a loss to the philistines at all. The books are going to an environment where they will be appreciated and used.”

Philistines indeed! The HRC is now home to nearly a million rare or significant books. In 2013, Stephen Enniss was appointed director, and under Enniss the Center has acquired the archives of Gabriel García Márquez, Arthur Miller and Ian McEwan.

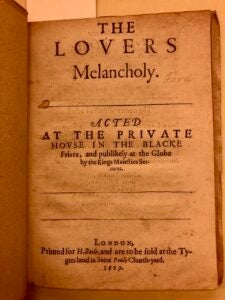

At least one of the books in the Pforzheimer collection is John Ford’s tragicomic play “The Lover’s Melancholy,” which Seile published in 1629. The title page reads: “To be Acted in the Private House in the Blacke Friers and publikely at the Globe by the King’s Majesties Servants. London. Printed for H. Seile and to be sold at the Tyger’s head in St. Paul’s Church-yard. 1629.”

But something besides books came from the Pforzheimer Foundation: It endowed a curator for the collection bearing its name and funding for most of the early books and manuscripts programming and acquisitions the HRC does. And who was the Pforzheimer curator for rare books but Dr. Aaron T. Pratt.

I set up an HRC account and watched the orientation video. That Thursday afternoon, I walked downhill to the HRC. Bypassing the museum gallery on the first floor, I took the elevator to the lobby of the large Reading Room. There, Kathryn of email fame greeted me, checked my ID, and gave me a key to the locker where I would stow my backpack. Presently, Dr. Pratt appeared, and so as not to disturb other researchers we sat on a bench in the lobby where I peppered him with questions for 45 minutes straight.

Then we entered the Reading Room and set up at a large table. First up was the granddaddy, so to speak, of Henry’s work, Cosmographie in foure Bookes, Contayning the Chorography & Historie of the whole World, and all the Principall Kingdomes, Provinces, Seas, and Isles, Thereof. They didn’t go for pithy titles back then, and some are much longer than that. One book after another came out as we continued discussing them in hushed tones.

So what did I learn?

I learned from a remarkable reference book Pratt had brought along the exact location against Old St. Paul’s Cathedral where Henry’s shop stood, and I mean exact to the foot. In it, Pratt showed me an account from the day stating that in the second story, just above the shop, “dwelleth Henry Seile.” This in turn enabled me to search up old paintings and etchings of the church and find the very door and upstairs window that would have been his.

“This was a semi-permanent structure.” Pratt described the shop in terms an Austinite would understand: “Customers would probably have encountered a building fitted with a window of the kind of you find on a modern taco truck: a flat board that comes down and a little bit of an awning, and you did business over the counter. That’s how a lot of businesses during this period worked.” Knowing details such as this — “It affects our sense of what the experience of buying books would have been like. It was not like walking into a Barnes & Noble.”

I learned that Henry would have been decently well off for someone who was not nobility or even a landed “gentleman,” and that the 16th and 17th centuries were a time of significant change for many people, who were beginning surround themselves with the trappings of the upper class even though they were not “blood.” “We start seeing relatively humble people owning wall hangings, silver and other luxuries,” said Pratt. “People were starting to buy themselves into the trappings of the class that they aspired to. And some of these guys had some serious coin. The fact that Seile became warden of the Stationers’ Company (London’s royally sanctioned trade organization for members of the book trade) means he wasn’t a nobody.”

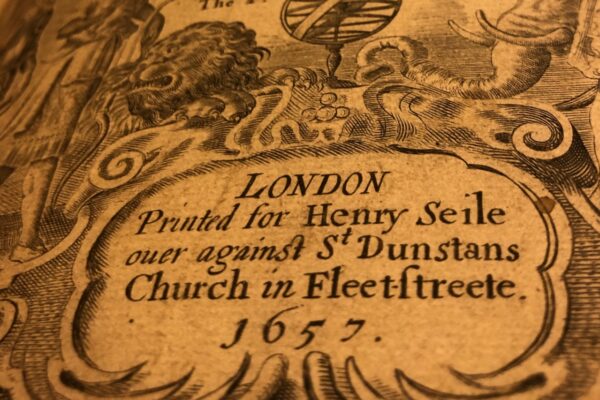

Shops back then not only lacked addresses, but lacked names too. So the title pages of Seile’s books say, “Sold at the sign of the Tiger’s Head in St. Paul’s Churchyard,” or, after he and all other merchants were evicted from the old Gothic cathedral, “Sold at the Sign of the Tiger’s Head over against St. Dunstan’s Church on Fleet-streete.” I learned from Pratt that the tiger’s head sign had marked this bookshop through at least three previous owners, going back decades, and Pratt showed me a book Henry had probably worked on in 1618 before he took over the business. Moreover, I learned Henry took the tiger’s head sign with him when he moved down Fleet Street, and then moved again, all three spots Pratt was able to point out to me on a map to within a block.

In one book, a tiny “f” was written on the title page, which Pratt explained was a pricing code. In another book, we could see where the first owner of the book had scribbled his name, and then the date: 1629. Except for the quill pen strokes, it looked like it could have been written 50 years ago instead of 392.

He explained that this was largely linen-based paper, which was made from rags including underwear, and which they treated with gelatin as part of the papermaking process. I learned that book binding was a whole other trade separate from book printing, and that supply-chain bottlenecks, as we’re all experiencing now, were a source of friction between booksellers and bookbinders.

He also explained that Henry’s days would have been filled with managing his apprentices, buying paper, subcontracting printers, hiring artists to engrave frontispieces and maps for the atlases, and trading some of his books for the books of others for retail.

Pratt followed up our visit with more helpful resources and documents, including photos of the original will of Henry’s widow, Anne, who continued his publishing legacy.

To say I had hit the jackpot — not only in having the Harry Ransom Center but in meeting Aaron Pratt as well — would be a gross understatement. It was clear that after 40 years of family research, thanks to good paper made of sturdy 17th century underwear, careful preservation by this world-class library, and an uber-knowledgeable curator, the paper trail I once thought had gone cold was now heating back up.