For a time in which America is not directly involved in a war, American national security professionals sure are busy. And a sizable number of them are alumni of UT’s Clements Center for National Security.

In Poland, a U.S. Air Force intelligence officer briefs F-15 Eagle pilots in the Grim Reapers squadron every day on the latest intelligence on Russian air force missions over Ukraine, Belarus and Poland. At NATO headquarters in Brussels, a U.S. Army colonel serving as senior adviser to NATO’s supreme allied commander in Europe coordinates the next phase of the alliance’s deterrence mission, including deploying more NATO forces to Poland, Estonia and Romania to bolster humanitarian relief and weapons-resupply lines and to block any further Russian invasions.

Meanwhile, a U.S. intelligence officer at a joint intelligence center in the United Kingdom collects signals, imagery and human intelligence on Russian troop movements and feeds that information to both Ukrainian forces and senior analysts at the Defense Intelligence Agency in Washington. There, a Ukrainian-speaking Texas Ex assesses the reports and prepares them for briefings to military leaders and the secretary of defense.

Though most of these alumni cannot be named for security reasons, Clements Center Executive Director Will Inboden knows them well, and they keep him and his staff up on their whereabouts.

“This is a story about UT and America,” says Inboden, “and the top line is this: In the last nine years, this university has produced a tremendous wave of young graduates — undergrads, masters, Ph.D.s and law students — who are now serving around the world in vitally important national security positions.” They range from uniformed military to CIA officers, State Department diplomats to National Security Council professionals, congressional staff members to think-tank analysts.

This is a story about UT and America.

Founded in 2013, the Clements Center for National Security reports directly to UT’s president. In less than a decade, it has built a network of more than 600 alumni, many holding influential positions with the National Security Council, CIA, State Department, Defense Department, Congress and leading think-tanks. “You show me a trouble spot in the world, and I’ll show you a Clements Center alum who’s working on it,” says Inboden. Off the top of his head, he rattles off an impressive list:

- In the western Pacific, aboard the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln, an F/A-18 Super Hornet Navy pilot prepares for his catapult launch after another Navy intelligence officer has briefed him on where he can expect to encounter China’s air defense systems as the Navy fliers conduct a freedom of navigation mission.

- A CIA officer who is posted in Asia coordinates with her host country counterparts to share intelligence on the threat from China.

- A diplomat at the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan, coordinates with CIA officers, the U.S. ambassador and Pakistani officials on the next phase of America’s counterterrorism strategy in the region after the U.S. exit from Afghanistan.

- A U.S. Army Green Beret officer deployed in Africa partners with local forces in counterterrorism operations against jihadist groups.

And, of course, Washington is thick with Clements Center alumni.

- In the Pentagon, a senior Army strategist is working for the secretary of defense to bolster the Army’s presence in Europe and to equip the Army with the right weapons, force posture and doctrine to deter Russia across NATO’s frontline.

- On Capitol Hill, a Senate staffer prepares the necessary legal authorizations to provide real-time, lethal intelligence targeting to the Ukrainian forces, while a Senate Foreign Relations Committee staff member prepares emergency legislation providing humanitarian, financial and military aid to the Ukrainian people and military.

- At the National Security Council, one staff member drafts a strategy to identify the primary threats to America, set policy priorities, and allocate resources for countering Russian and Chinese aggression, while another develops a specialized China strategy.

Not only are they serving their country in those trouble spots, such as Eastern Europe, China and Pakistan, they form a de facto young Longhorn alumni network. “They’re staying deeply connected with each other. They’re encouraging each other, helping each other with their careers,” says Inboden. And even if they haven’t kept in touch, they will show up to the same secure facility in far-flung locations and recognize one another from UT. “I think it’s tremendously inspiring,” he says. “It’s also a real encouragement to our current students.”

Other alumni are serving as faculty members teaching diplomatic and military history and security studies across the country, including at the Naval War College and the Naval Postgraduate School, the Air War College, West Point and civilian universities such as Duke, Notre Dame, Ohio State and Williams College.

In all, the center’s staff estimates that more than 150 recent alumni hold federal positions. The lion’s share is in the executive branch, with many of those in the intelligence community and at the State Department. But as noted above with the congressional aide, they also serve in the legislative branch, and, because Clements often partners with UT’s Strauss Center for International Security and Law, it claims several alumni in the legal realm as well. “Through our alumni,” Inboden says, “you can see the sinuous connectivity across the whole of the national security system.” Still others work on security issues in state government, such as with the Texas Department of Public Safety.

Outside of government, other alumni serve in think tanks and work for closely connected federal contractors.

Program coordinator Amber Howard works to bring young alumni back to speak, do mentoring sessions or give advice on internships and jobs. “I so rarely have an alum who has said they don’t have time. They always have time. They think, ‘Oh yeah, the Clements Center. The kids we’re going to get are coming from this.’ ”

A Center of Concentric Circles

The Clements Center is an unusual animal in academia. Very few other universities have similar centers focused on applying the lessons of history to current national security challenges and training undergraduate and graduate students to be the next generation of national security leaders. “Student involvement is best pictured as concentric circles,” Inboden says. There’s a core group of 80-100 students with whom the center interacts almost every week, and many of those are majoring in international relations. Chief among those are 30 to 35 undergraduate fellows. Each year, around 80 applicants compete for 20 new positions; the rest are fifth-year seniors serving a second year.

The next circle out, perhaps an additional 200, would be students who come to a guest lecture a couple of times a month, attend informal policy discussions, or take classes sponsored by the center. Furthest out would be the roughly 1,000 students who interact with the center once or twice a year through events such as major conferences or the annual National Security Career Fair held on campus.

The center offers a certificate in security studies for undergraduates, which about 150 students are pursuing at any time. Each year, Clements sponsors an introductory undergraduate class informally called “Intelligence 101” taught by Paul Pope, a former CIA case officer who along with fellow CIA veteran Steve Slick runs the Clements-Strauss Intelligence Studies Project. That course has about 80 students, and each year a number of them get jobs in the intelligence community.

The Clements Center has become a physical intersection and an intellectual intersection at every level.

On the graduate side, the center has about 50 master’s students in a portfolio in security studies and a graduate fellows program consisting of about 25 Ph.D. students a year.

Reporting directly to the UT President’s Office has made it easier to work across the campus, collaborating with faculty and students in the LBJ School of Public Affairs, Liberal Arts, Law, Engineering and elsewhere. With the McCombs School of Business, the center just established a new minor in business and national security.

“The Clements Center has become a physical intersection and an intellectual intersection at every level,” says Associate Director Paul Edgar. “It’s become almost a cyclone or funnel bringing in good people that otherwise would not be together.”

The Clements Center also works with many active-duty military students and student veterans.

It Can All Start With Coffee

On a Friday at 1 p.m., 40 students pack into a conference room in the Flawn Academic Center, just down the hall from the Clements Center offices. They sit at tables arranged in a hollow square, and with every chair taken and another 10 students standing along the walls, the group cuts up with inside jokes about OSINT versus HUMINT. (That’s spy jargon for open-source intelligence versus human intelligence.) At a side table, late arrivals quietly get coffee and look over the free snacks.

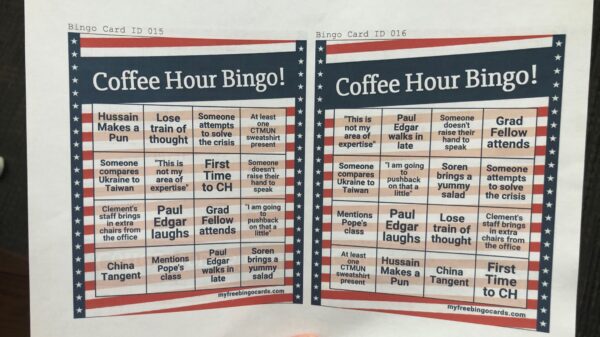

Program fellows, selected each year from among the seniors, are introducing the topic of the hour, while Amber Howard hurries around the room verifying bingo cards and handing out Clements Center swag as awards. Bingo card squares include: “Hussein makes a pun,” “Paul Edgar laughs,” “Someone compares Ukraine to Taiwan,” “Clements’ staff brings in extra chairs from office,” “This is not my area of expertise” and “Soren brings a yummy salad.”

This is Coffee Hour. In a March 2022 article from the U.S. Naval Institute magazine titled “Military Leaders Need the Liberal Arts,” UT alumnus and Navy officer Nicholas Romanow described it:

“My most direct exposure to a liberal arts approach in action was when I participated in a series of discussions called ‘Coffee Hours’ hosted by the University of Texas’ Clements Center for National Security. On alternating weeks, a student would moderate a discussion on a strategic issue open to all students on campus, regardless of their field of study. Because these discussions were open to students of all backgrounds, they always granted a multidisciplinary view on a given national security issue. Philosophy or engineering students with little background in international relations coursework often had immensely valuable insights on everything from competition with China to the ethics of drone warfare. They also helped students formulate their thoughts, articulate them, and answer rebuttal questions on the fly. These discussions generated many questions but few definite answers, leading participants to appreciate the nuances of these ‘bigger picture’ issues.”

This day, the conference room brims with international relations majors, Arabic majors, history majors and engineering majors, and they are debating the benefits and the pitfalls of scraping Twitter accounts to discern when the Russian invasion of Ukraine would begin.

Soren (of yummy salad bingo fame above) is senior Soren Ettinger DeCou, a Plan II major and Forty Acres Scholar who is a biomedical engineering major but can’t get enough of the Clements Center. “These programs take up the majority of my time because I love this organization so much,” she says. She feels not enough policymakers have a scientific background and hopes eventually to work at the federal level translating technological information for nontechnical audiences.

Ettinger DeCou says Associate Director Paul Edgar has been the most important person in her UT education, and she paints a telling portrait of the close ties that form here. “His mentorship over the last four years has been absolutely invaluable. He combines practical foreign policymaking experience with creativity. He was a lieutenant colonel in the Army, and he combines that with an ability to have really deep, nuanced discussions about anything,” she says. “We’ve spent hours talking about life and futures.”

Ettinger DeCou did a virtual internship for the US Embassy in Beijing during which she produced a short video in English and Mandarin describing to a Chinese audience her excitement over voting for the first time.

I so rarely have an alum who has said they don’t have time. They always have time.

Fellows pick the topics several weeks ahead. “They don’t need to be experts in the area; it’s just something they’re interested in that’s going on in the world around them that they want to pick the brains of their peers about,” Howard says. “North Korea’s nuclear program, Iran deterrence, Russia, cryptocurrency — anything they find fascinating.” Howard then works with them to select policy articles to present to the students.

Because Coffee Hour sessions are open to everyone on campus, they create plenty of opportunities for students to practice moderating lively discussions, a skill that will serve them well as national security professionals. “How do you manage a conversation? How do you manage someone who is over talking their time?” asks Howard. “When someone disagrees with you? When someone interrupts you? How to disagree appropriately and how to get back into a disagreement in a healthy way? We’ve lost a lot of that obviously recently in America. How do you engage with someone who is not on your side of the table? They really do a fabulous job.”

Perhaps the most telling detail of Coffee Hours, though, is that all this effort is expended and excitement generated over something for which students get no academic credit.

A student once told me that Clements was able to provide a private, liberal arts-like sense of community within a large public university, and this I believe is quite rare.

Alexandra Foggett helps manage the operations of Clements Center’s programs including the Undergraduate Fellows Program and Coffee Hour, a Maymester in London and a two-week trip to Israel and the Palestinian territories. “Most importantly, our team provides a system of support to help students narrow down their interests, navigate transitions post-graduation and cultivate a strong sense of community both at UT and within our thriving alumni community now pursuing foreign policy careers across the globe.”

She adds, “There are many fantastic centers and programs at universities across the country, but I do believe the Clements Center is unique in many ways. A student once told me that Clements was able to provide a private, liberal arts-like sense of community within a large public university, and this I believe is quite rare.”

All portraits by Bonnie Berry