An associate director and a security guard. That’s who remained.

It was late March 2022, and the Texas Memorial Museum had just closed its doors — with no clear plan for how it would reopen again. In the Great Hall, where, for decades, hundreds of thousands of Texas schoolchildren once had craned their heads upward in wonder, the world’s largest flying creature ever, Quetzalcoatlus northropi, soared in dim silence, as a quarter inch of dust on the limestone walls surrounding the pterosaur continued to grow.

“I wasn’t assuming it would all work out, but I’m pretty stubborn,” says Associate Director Pamela Owen, who has been with the museum since 2003. “Part of me said, we’ve got to keep on fighting to keep the museum going. I love this place.”

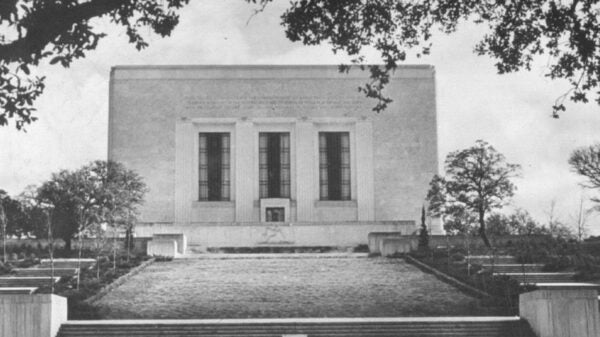

What had begun 87 years earlier out of scientific necessity and in a grand flourish of state pride — its ground broken by FDR, its monumental art deco building designed by UT Tower architect Paul Cret, its contents having included treasures of state history and natural history alike — at last had flatlined. Perhaps the Texas Memorial Museum was simply something whose time had passed.

But this week, the museum opens again — with stunning new exhibits, a new business model, a refined focus and a new name: the Texas Science & Natural History Museum. (Since the words Texas Memorial Museum are etched on the structure, it is still the Texas Memorial Museum Building.)

Many people wanted to revive the museum, but one of the first fortuitous events came about because of a gift given decades earlier. State Rep. Glenn Rogers, a rancher and veterinarian from North Texas, had heard that the museum long had held some artifacts once in his family. Rogers wanted to see them, and the request worked its way to President Jay Hartzell’s deputy for governmental affairs and initiatives, Andrea Sheridan.

Sheridan and her colleague Jenna Watts, director of state affairs, arranged a field trip to the museum with Rogers. Sheridan and Watts both were overwhelmed with sadness on seeing the storied museum struggling to remain open. “It pulled at our heartstrings, honestly,” Sheridan said. “We left there, and said, ‘Is there anything we can do to save this museum?’” Reviving the museum became a passion project for the whole government-affairs team.

Sheridan reached out to Hartzell and to David Vanden Bout, who had just become dean of the College of Natural Sciences. That same spring, Vanden Bout had launched a project examining opportunities to improve public engagement with science at the University, and the museum emerged as an area of real opportunity. Sheridan suggested forming a small advisory group to study how the museum might be made self-sustaining. Hartzell and Vanden Bout enthusiastically agreed, and the group of five convened. They included Rita Ashley, Richard Craig, David Anderson, Kim Bonnen and Michelle Skupin — each bringing varied expertise and connections.

Their first report stated that reviving the museum would require a full-time executive immediately — someone who could think big-picture, make executive decisions, network, ask for support, ride herd on contractors and put fresh eyes on the museum. Many people thought of the same person. It was Vanden Bout who sent the text: “Carolyn, I have a project for you.”

Energetic and extraverted, Carolyn Connerat came to UT in 2005 as director of annual giving and had a variety of roles in development and communications before joining the Provost’s Office, from which she recently had retired as vice provost for enrollment management, overseeing a large and complicated portfolio that included UT admissions. “I failed at retirement!” Connerat says with a laugh. She agreed to be the managing director of a closed museum.

The charge from Hartzell and Vanden Bout was simple and came in the form of a two-part question: What do we need to do to make this museum self-sustaining, and if it can’t be, what do we need to do to close it?

“I think the museum actually closing and running out of money was a great thing,” Watts says, “because it provided the opportunity to reimagine it.” Hartzell and Vanden Bout each kicked in funds from their respective budgets, and the state agreed to a one-time appropriation of $8 million. Philanthropic support also started to arrive. Soon the museum had $12 million for the next three to four years to build a bridge to self-sustainability.

The museum had begun with a need. Texas paleontologists, many of them on UT’s faculty, noted that, just as British museums had removed cultural treasures from Egypt and Greece, museums outside of Texas, particularly in the Midwest and on the East Coast, were removing the most valuable fossils from the Lone Star State because Texas had no museum to properly preserve and display them. Scientists had been pushing for years for a natural history museum at the University. “If a Texas student or professor of geology has need to examine a specimen of Dimetrodon, found only in Texas Permian beds, he would have to visit a museum in Chicago, Michigan, or the East,” complained UT professor F.L. Whitney in the 1920s.

But it was not until the scientific need got coupled with state pride that things began to happen. As the Texas Centennial of 1936 approached, the Legislature funded more than 1,000 monuments across the state to commemorate its independence. These included the transformation of Fair Park in Dallas and the building of nine museums including this one.

The Legislature established the museum and funded part of its construction, but the federal government chipped in $300,000, and a Centennial Committee sold commemorative coins to raise more money.

Paul Cret, architect of the UT Tower, designed the building. Cret’s scheme called for two additional wings on either side of what we see today. When the money could not be raised to fund the whole structure, Cret quit. This explains the museum’s relative smallness. While most other museums in the state have 200,000 square feet of exhibit space, this one has 18,000. The upside, especially for families, is that the whole museum can be appreciated in about 90 minutes.

“How often do you see families on campus and they’ll ask you ‘Where do we go?’ Well, you can go to the Blanton Museum of Art, which is great,” Connerat says. “You can go to the LBJ Presidential Library. But if they have small children, now you can say they can go to the Texas Science & Natural History Museum. It will be a huge draw for visitors.”

Despite being two wings shy of Cret’s vision, it is still an art deco gem and an awe-inspiring, temple-like sight that sits majestically atop the hill that was once a part of Wheeler’s Grove and the site of Juneteenth celebrations in the late 1800s.

* * *

Connerat and Owen convened the advisory group, and together they traveled the state studying how other natural history museums succeeded: the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas; the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon (another Texas Centennial creation); and the Witte Museum in San Antonio. Finally, they visited a not-so-small museum, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

The group found that, without exception, self-sustaining museums rested on at least three legs: admission charges, membership programs and rental fees for private events. By contrast, the Texas Memorial Museum had only admissions, a line in the College of Natural Sciences budget, and $75,000 a year from the state, which in 2021 had been zeroed out.

Without exception, self-sustaining museums rested on at least three legs: admission charges, membership programs and rental fees for private events.

Some 16 private events already are scheduled for the fall, half of which are rentals. These include a nonprofit gala, advisory council meetings, and yes, a wedding with the ferocious dinosaurs attending. Some 150 can be seated for dinner in the Great Hall, or 250 for a reception. The patio can seat 250 as well.

Connerat says, “We’ll still need philanthropic partners to finish the exhibits that we want to do and build back the educational program. We’ve always been a resource for schools in Texas. We have pictures from the 1940s of buses parked on San Jacinto and children running up that hill. Literally, they’ve been coming here for 70 years. You want that to continue and increase.” She hopes that eventually philanthropy will cover the admission for schools in low-income areas.

“I feel so much more confident in our future,” Owen says. “This was the trial by fire that we needed to shake things up and also give us time to think about what really is the purpose of this museum.” For a long time, her own job has been one of simply keeping the doors open. Now, she gets to think about exhibits and programming again — questions such as striking a balance between traditional exhibits that people have come to love over the decades and the need to exhibit new research. “It’s like a tree, where you can go out to various branches but everything is connected to the natural world,” she says.

What’s New and What Remains?

The advisory group’s field trips prompted many improvements: The space has always been majestic, but the echo of the floors has made conversation nearly impossible. The idea for carpet tiles on the upper floors to improve the acoustics came from the Perot Museum.

Better lighting shows off the exhibits and gives the galleries a fresh feel. Replacing the old fluorescent lights from the 1960s with LED lighting that can be programmed to any color in the Great Hall will make the space customizable so if a couple’s wedding colors are blue and green, done and done. Burnt orange, even better!

Great Hall Level

The Great Hall, finished in Pyrenees marble at the bottom and Texas limestone above, and showing seals representing the six nations Texas has been part of, was cleaned top to bottom. A Chicago company used lasers to remove a large stain on the wall left by an HVAC unit and vacuumed the entire area, 87 years of dust, a quarter inch.

The Great Hall’s enormous windows to the west had been draped with curtains that darkened the room excessively and also covered the windows’ interesting etched design. Now ultraviolet shades through which the design shows can cover the windows but keep out the heat. (The old curtains, made by interior designer Dorothy Liebes, have historic value of their own, and the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York asked for a sample of the fabric.)

Sharing the Great Hall with the cast of the 33-foot wide Quetzalcoatlus northropi (the fossilized bones of which reside at UT’s J.J. Pickle Research Campus) is a new cast skeleton, a tyrannosaur 33 feet long from skull to tail, and also found in Big Bend National Park. (The jury is still out as to whether it is a juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex or a new species.) Hence, the Great Hall is now labeled Texas Titans. On its west wall, a mural shows what Big Bend would have looked like when these animals were alive, and what the animals looked like with their skin on.

Other than the tyrannosaur, the floor has been cleared to facilitate events such as dinners and receptions, and a new portable platform at one end of the hall will act as a low stage during events.

The side gallery off the Great Hall now features the story of life in the natural world from the beginning of deep-space time through the prehistoric era to the present and shows the impact humans have had on the planet. The minerals and gems once here have moved to a new gallery at the Jackson School of Geosciences.

The Paleontology Gallery — While the Great Hall is the architectural star of the show, the first floor, downstairs from the Great Hall, contains the densest display of the University’s most valuable fossil specimens. These skeletal giants, such as the fearsome 30-foot Onion Creek Mosasaur and a glyptodont, looking like an armadillo the size of a Smart car, remain where they have been. The lighting is updated, and work on new signs and other updates is now getting underway.

Discovery Center – Owen, who was once one of the paleontologists who helped visitors identify specimens they had brought in at the Paleo Lab desk during the popular Identification Days, looks forward to having this program return as this area will be greatly expanded for more hands-on learning, especially for children. (During COVID, she identified fossils by photos sent in email.) “I’m growing my volunteer corps again,” she says, adding, “I love it because it gives people a chance to talk to really friendly, cool experts who will tell them about the rocks or fossils they bring in.”

The Hall of Texas Wildlife — Up on the third floor remains the exhibit of taxidermized Texas specimens, many that were a part of the original Texas Centennial celebrations. The bison were actually displayed on the court in Gregory Gym during UT’s Centennial Exhibition. “I’ve been surprised at the number of people who’ve said: ‘I really love that exhibit. It’s amazing. I really want that to stay,’” Connerat says. Though impressive displays of preserved animals can be seen today at sporting goods megastores, these creatures are museum-worthy simply because they were part of the Texas Centennial and because these very specimens roamed Texas a century ago.

Also on the third floor will be a new gallery dedicated to the history of the museum itself. This space hearkens back to a comment Watts heard in the early brainstorming about the museum’s comeback: “Do you know what this thing is? It’s a museum of a museum.”

Science Frontiers — The fourth floor will showcase the research that the University is doing today that will make a positive difference in the natural world — such as in biodiversity, sustainability and vaccines. “To actually have a place to explain the research we’re doing and why it matters — that’s exciting,” Connerat says.

And lastly, there is a new conference room that can double as a classroom or a bride’s room. “Since we’re going to have weddings, we have to have a bride’s room!” says Connerat.

Outside, you will find a pollinator garden as part of the new sustainable landscaping, designed in part by experts from the University’s Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. During football season, you will also notice a 150-by-26-foot tent on the patio for hosting game-day receptions and other events. There might also be collaborations with Texas Performing Arts, such as receptions before or after the Broadway shows playing next door.

The dinosaur tracks from Glen Rose are still housed in a 1940 Works Progress Administration-built outbuilding that has seen better days. The tracks will remain, but look for major changes in how they are displayed in the coming years.

The grand opening of the Texas Science & Natural History Museum, sponsored by HEB, will be Saturday September 23, 10 a.m.-2 p.m, with free admission all day. When the museum opens the following week, general admission is $10, with discounts for senior citizens. Admission is free to UT ID holders, children under 4 and active military members.

A second phase of improvements will continue updating displays throughout the museum. Instead of simply “Pardon our dust,” the temporary signs read: “We’re evolving.”

Photos by Trent Lesikar. Video by Ayden Castellanos.