Not many 90-year-olds look this good. In fact, Hogg Memorial Auditorium has never looked better.

After a two-year, $27.8 million renovation, the first auditorium at The University of Texas at Austin has reopened and is already reclaiming its historical role as a lively hub of student activity. With 1,007 seats and situated on the west edge of campus, the elegant Beaux-Arts-style venue, which for its first four decades was an unsurpassed premier auditorium in Austin, fills a unique niche.

The first event held in the restored auditorium was the visit of U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken on Oct. 4. Last week, the auditorium was used on short notice when student interest in a visit by presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy overwhelmed the originally planned venue. The line outside of Hogg stretched over a city block, and just like that, Hogg had returned to its former status as a campus hot spot.

“It’s very emotional for me,” says Soncia Reagins-Lilly, UT’s vice president for student affairs and dean of students, who oversaw its decadelong climb back from disrepair and declining use. “It’s such a great opportunity to revive and to bring back into student life such a historic facility. Every time I go in there, I’m near tears. I’m extremely happy to be part of that legacy and that return.”

A big part of that legacy centers around live music, and the first performance at the restored auditorium will be a concert for UT students and invited guests by blues-rock musician and Austin-native Gary Clark Jr. on Oct. 27.

Historically, Hogg has bookended the student experience, hosting hundreds of freshman orientation sessions as well as graduation ceremonies for many departments. In between, glee clubs, step shows, the annual Texas Revue talent contest and other student productions have filled the hall. Many a final exam was administered there as well — with seats between test-takers to quell the wandering eye — all of which Mulu Ferede, executive director of University Unions, says will resume.

Its size fills a entertainment niche — larger than Bates Recital Hall (700 seats) but smaller than Bass Concert Hall (2,900 seats). But more importantly, because Hogg is overseen by University Unions, a department in the Division of Student Affairs, it is tightly focused on the student experience and student organizations, as distinguished from large-scale shows brought in for the public.

Singer-songwriter Darden Smith, B.A. 1985, has a 35-year relationship with the University Unions, having played the Cactus Café in the Texas Union well over 60 times. This year, he became UT’s inaugural singer-songwriter in residence. His memories of Hogg include seeing symphony concerts there as a student. “It’s not just beautiful,” Smith says, “it’s inspiring. That’s what music venues like that do for us — they inspire us. It’s a great place to be, but it’s also a great place to pick up the energy. The fact that UT has the awareness now to make this beautiful institution viable — I think it speaks to the long-range vision that they have for bringing music back and making music an active part of campus. I just think it’s fantastic.”

That emotion is echoed by UT President Jay Hartzell. “UT students have been entertained, challenged, inspired and educated by events at Hogg Memorial Auditorium for nearly a century, and I am thrilled it’s not only back but better than ever,” says Hartzell. “Taking a historic gem like Hogg and bringing it up to modern standards for performing arts, safety and accessibility while also preserving its architectural charm wasn’t easy, and I thank the Division of Student Affairs, University Unions, our previous student leaders and everyone who made it happen. This renovation brings a key part of campus life back to where it belongs, while we continue to invest in the vibrancy of our campus and its contributions to Austin’s arts and music culture.”

Hogg History

Tom Ward, a retired U.S. Foreign Service officer, attended the Blinken event that reopened the venue and called the renovation “really wonderful.” If anyone should know, he should. Ward remembers attending plays there as a boy in the 1940s, when the Clare Tree Major Players of New York, who specialized in productions for children, would play in the auditorium every year for school kids bused in from throughout Austin.

“I’m a native of Austin, and I’ve been around a long time,” says the 91-year-old with a chuckle. As a UT student, Ward, B.A. 1954, saw mostly popular music at Hogg, and as a UT admissions staffer in the late 1950s, he saw the folk sensation the Kingston Trio there. (Gregory Gym and the Union Ballroom were the only other venues on campus to hear music, and Ward remembers world-famous conductor Arturo Toscanini bringing the NBC Symphony Orchestra to the Greg in 1950. “It was hot as hell in the unairconditioned building,” he recalls laughing. “Toscanini took off his coat during the performance.”)

Hogg Memorial Auditorium commemorates Gov. Jim Hogg and his son, Will C. Hogg, an early Regent and pivotal figure in University history who died in 1930, “their services having been based on an intense devotion to the public welfare that was combined by a great capacity to advance it,” as the Regents declared.

Designed by French-born architect Paul Cret in the Beaux-Arts style and built for $300,000, Hogg was part of the “Union Group” buildings financed almost entirely by student and alumni efforts. Completed in 1933, it stood several years before Cret’s most famous campus building, the Tower, was built. Cret also designed Hogg’s neighbor – the Texas Union, which also marking its 90th anniversary this year.

The facade was designed to resemble a skene, the structure behind the stage in Greek theaters from which actors would emerge to perform their scenes. The three stone faces represent the three types of Greek plays: comedy, satyr and tragedy. Tragedies and comedies need no definition, but the middle one is less known. A satyr is both a mythological character and a genre of play. Satyrs were male nature spirits with the legs and ears of goats or horses, and — well, just look it up; it’s a whole thing. In satyr plays, which were parodies of tragedies and known for their obscene humor, comically hideous satyrs made up the chorus. “The fact that the Hogg Auditorium has included the face of a satyr is highly unusual since most modern theaters only depict the Greek dramatic masks for comedy and tragedy when paying homage to their classical foundations,” states a blog post of UT’s Classics Department devoted to classical references in campus architecture. (Despite the closeness of the words and even of the concepts of parody and satire, satyr is not the origin of the word satire.)

Hogg was supposed to open on Monday night, April 24, 1933. America’s foremost poet, Robert Frost, was set to take the stage for a reading and lecture. But the supervising architect called it off, citing wiring issues that made the lighting system unsafe. Frost instead gave his talk across Guadalupe Street at University Baptist Church.

By that Thursday, the wiring issues had been sorted out, and the auditorium’s first event was UT’s 50th anniversary program. Regent H.J. Lutcher Stark, on behalf of his mother, Miriam, presented UT a priceless 1529 parchment signed by Charles V of Spain conferring on Hernán Cortés the title of captain general of New Spain. Experts called it one of the three most important historical documents in the world regarding the Americas. (Today it is at the Harry Ransom Center.) President H.Y. Benedict then delivered a short address “reviewing the University’s accomplishments, her shortcomings, and her future needs.” The entire program was interspersed with songs by glee clubs.

For more than 40 years, until the mid-1970s, Hogg was an unsurpassed performance venue in Austin, and it was not eclipsed on campus until the performing arts complex anchored by Bass Concert Hall was opened in 1981. The Hogg stage has hosted thousands of events such as speeches and lectures and professional performances including plays, concert pianists, string quartets and full symphony orchestras. John Legend played there in 2012.

In the 1950s, Hogg was the main stage for UT’s drama department. For many years, Hogg was used for film screenings and will be again. When independent journalist Max Raskin recently asked Wes Anderson which movie theater he had been to the most in his life, Anderson, B.A. 1990, replied that since he was a projectionist at Hogg auditorium, “that may be the one where I have spent the most time. It’s a big room.” In 1997, it reopened as a performing arts venue under the College of Fine Arts.

The Resuscitation

Reagins-Lilly, who arrived on the Forty Acres in 2006 as senior associate vice president for student affairs and dean of students, has spent a lot of time in Hogg and knows every stairwell, backdoor and greenroom. One of her roles has been to welcome every cohort of student orientation, about a dozen each summer. “Over time, we started having student productions — musical performances, comedians. It was a hub. It was one of the facilities originally designed for student life, and that’s how it was primarily used before we had the Black Box (Theater) in the William C. Powers, Jr. Student Activity Center, so Hogg was a prime location.”

In 2011, Natalie Butler and Ashley Baker Hayes became president and vice president of Student Government. Hayes had been hearing from student organizations on campus that it was very difficult to secure spaces on campus and had been simultaneously noticing that Hogg was basically mothballed. She came to Reagins-Lilly and asked why. “Whenever you’re in student leadership, you’re always looking for different things to fix on campus, looking to improve the student experience,” says Hayes, B.A., B.S. 2012, who now works in government affairs at Charter Communications. “You might not see the change while you’re on the Forty Acres, but it’s exciting to know that over 10 years later, something that I had a small hand in is able to really help students moving forward.”

Reagins-Lilly says, “We began to explore and discovered that the auditorium was originally within the University Unions auspices but had been moved under and was being programmed by the College of Fine Arts.” She met with then-Fine Arts Dean Doug Dempster and discussed how the location was ideal for students — adjacent to the Texas Union on the West Mall and near West Campus. Additionally, they agreed it was not optimal for large-scale productions of the kind the College of Fine Arts/Texas Performing Arts excels in staging, with its small wings, little parking, and 1930s amenities, which professional performers might be underwhelmed by but which students would be elated to have. Dempster agreed to repatriate it to the Division of Student Affairs.

But even in the dimmer light of predominantly student use, by 2020 the building’s deterioration could no longer be tolerated. “My major concern was no railing in the balcony,” says Reagins-Lilly.

Hogg Warts: The Infrastructure

“Infrastructure was the primary driver,” says James Buckley, director of facilities and operations of the University Unions. Claudette Campbell is director of operations for the Texas Union and Hogg. For years the fire marshal would take Campbell’s earnest word that they were about to renovate and would clear it to be open another year, but “I think at some point we would have been shut down,” she says.

Finally, after removing the seats to allow Brené Brown in 2021 to build a set and film her “Atlas of the Heart” series in the auditorium, Hogg was closed.

A completely new electrical system, costing $7 million, replaced dilapidated electrical switch gears and generators.

The building’s new transformer is a saga unto itself, and it delayed the building’s opening by several months as it was en route through a bottlenecked Panama Canal. When it arrived, it was brought through the large backstage door and then lowered through a giant hole in the stage level to its final home in the basement before the stage was reconstructed. Hogg transformers also power the nearby Biological Laboratories.

“When you do a renovation project of historical significance, it’s tough,” says Ferede. “I think specifically for this building the electrical, the part you don’t see, was really the most challenging. It also happened to coincide with the COVID, and so there were numerous supply-chain issues.”

Ferede describes the old mechanical room as “a mess, with suffocatingly low ceiling heights and closely spaced mechanical equipment.” They doubled the size of the mechanical room underground with a horizontal drilling operation to remove soil. Brand new ductwork was installed in the ceilings, and the building got an all-new water supply.

Then there was the roof. “Before, when it rained, the trash cans had to be scattered everywhere to catch the leaks,” Buckley says. Campbell adds, “We called it ‘water features.’ You literally could not sit in a quarter of the balcony.” A new roof cost another $7 million. They removed the clay Spanish tile, replaced the substrate, and put the original tile back on.

Another big improvement visitors will eventually discover are the restrooms. “People used to come to events and could miss almost the entire show waiting for a restroom, particularly women,” Buckley says. In the ladies’ restroom, there were signs in every stall reading: “Do not flush during performances.” They have replaced the two restrooms with no fewer than 14, most of which are single-occupancy, including several that are handicap accessible. The balcony level, which previously had no restrooms, now has four.

Lee Bash, UT’s longtime executive director of development events, associates Hogg with large annual events he produced for UT’s Littlefield Society donors. Some 15 years ago, he brought in 1950s pop phenom Patti Page. “We discovered during setup that there were bats flying around in Hogg auditorium, far out of reach. Obviously we couldn’t have a theater filled with our top donors with bats flying about.” He called facilities, and they dispatched “bat wranglers,” brave custodians armed with long poles with nets at the end. “As you can imagine, this did not go smoothly,” Bash recalls smiling. “The bats proved to be quite elusive. After watching for a while, I excused myself and asked them to let me know when, and if, they were successful. I got a call later that day to say they had indeed caught the bats, after significant wrangling time. The next year, or maybe two, we had to do it all again.”

Campbell says if the backstage doors are left open for any amount of time, “they will be guests in the building.” But Bash is hopeful that with the restoration, fewer bats may taking the stage.

The Visible Improvements

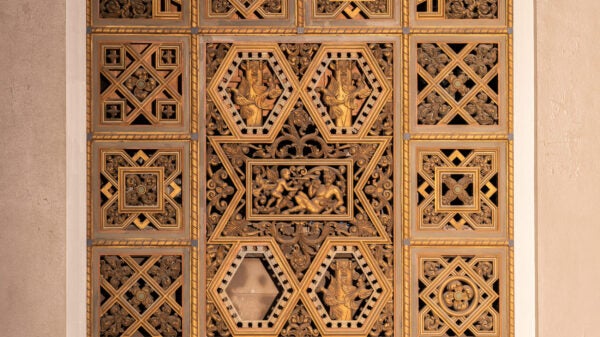

“The first thing you saw was peeling paint,” says Campbell of the lobby. That is gone — in its place, new ornamental woodwork that dampens the acoustics in the lobby and was inspired by the geometric shapes of the original carved plaster surrounding the stage.

The box office in the lobby and the vestibule between the lobby and the auditorium were removed, and the interior doors veneered. The side doors, which were solid wood, were rotten and have been replaced by replicas.

In the auditorium proper, visitors are greeted by new seats, replicas of the originals but now blue instead of green to match a new color scheme designers felt was truer to the 1930s. The orchestra pit was removed, and the first two rows of seats are removable should a production require the space.

Originally along the aisles, each end seat had a decorative steel plate with a Longhorn head and an interlocking UT. All but two had been stolen over the years, so replicas were produced to restore that design element. An artisan spent six months repairing and hand-painting the elaborate geometric lattice of plaster that frames the stage.

The auditorium’s large windows now can be darkened for performances or movies by lowering motorized shades or lightened by raising them when more daylight is desired, revealing the historic Battle Oaks. Energy-saving and other measures have brought the building so far that it has been submitted for LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification, a difficult designation for old buildings to achieve.

The new stage, made of medium-density fiberboard, is equipped with virtually every kind of audiovisual jack. They have added a greenroom to the stage level and outfitted it with 90-year-old furniture from the Texas Union. A new wheelchair lift backstage now makes the stage level handicap accessible.

The theater had seven battens, the long metal pipes suspended above the stage that can hold curtains, lights or scenery. Sixteen more motorized battens were added, and now every batten can be moved up and down with a joystick.

There is cinema-quality digital projection in the projection room above the balcony for the Wes Andersons of tomorrow and a new front-of-house mixing board at the back of the main seating level. The auditorium is completely set up for streaming as well. “For artists, in their contracts and riders, this is what the new standard is,” says Buckley, adding that, in terms of theater technology, Hogg is now cutting edge.

This renovation brings a key part of campus life back to where it belongs..."

“For a campus like UT Austin, whose slogan is ‘What starts here changes the world,’ it was kind of a shame that this was the facility we were operating and inviting the campus community into. So now, for this moment in time, we’re there. We’re the best you can be in terms of technology and amenities for a world-class institution,” he says.

Curtain Call

“Hogg is really supposed to reflect the spirit of Austin: live music,” Ferede says. “That live music should be experienced by our students. The students can also host programs in the space. They can perform on stage. They can watch an event. It’s really to integrate the UT experience in that area, so when they graduate, they have a shared memory of what the Forty Acres looked like. We are very much interested in the spirit of Austin and live music, and that ties to the University’s strategic plan.”

Ferede adds, “Our hope is that the students use it. This is an iconic building for the campus. I think it will leave an impression on the students here and when they leave. I hope they experience it.”

“If there’s something you’re advocating for, keep working on it,” says Student Government alumna Ashley Baker Hayes. “You might not see the benefits while you’re on campus, but you’re helping to make the Forty Acres a place for future students to be able to utilize and be excited about. Who knows what will happen in 10 years from the little seed you helped plant?”

Reagins-Lilly looks forward to students creating new memories in Hogg. “The staff there is so incredibly flexible in terms of making it available, and we will prioritize our student organizations so they can have their cultural performances there, their comedy shows, their step shows for our sororities and fraternities. It will be a premier center of student life, designed for the arts, designed to showcase all of our students and their talents. I hope it’s a beacon of belonging, for students to say, ‘I belong here. That’s a space for me to experience and to learn.’”

New photos of auditorium by Trent Lesikar. Black-and-white photos courtesy UT’s Briscoe Center for American History. Thanks to alumnus and UT-history expert Jim Nicar for archival photo research.