AUSTIN, Texas — It first appeared as a glowing blob from ground-based telescopes and then vanished completely in images from the Hubble Space Telescope. Now, the ghostly object has reappeared as a faint, yet distinct galaxy in an image from the James Webb Space Telescope.

Astronomers with the COSMOS-Web collaboration have identified the object AzTECC71 as a dusty star-forming galaxy. Or, in other words, a galaxy that’s busy forming many new stars but is shrouded in a dusty veil that’s hard to see through — from nearly 1 billion years after the Big Bang. These galaxies were once thought to be extremely rare in the early universe, but this discovery, plus more than a dozen additional candidates in the first half of COSMOS-Web data that have yet to be described in the scientific literature, suggests they might be three to 10 times as common as expected.

“This thing is a real monster,” said Jed McKinney, a postdoctoral researcher at The University of Texas at Austin. “Even though it looks like a little blob, it’s actually forming hundreds of new stars every year. And the fact that even something that extreme is barely visible in the most sensitive imaging from our newest telescope is so exciting to me. It’s potentially telling us there’s a whole population of galaxies that have been hiding from us.”

If that conclusion is confirmed, it could mean the early universe was much dustier than previously thought.

The team published its findings in The Astrophysical Journal.

The COSMOS-Web project — the largest initial JWST research initiative, co-led by Caitlin Casey, an associate professor at UT — aims to map up to 1 million galaxies from a part of the sky the size of three full moons. The goal in part is to study the earliest structures of the universe. The team of more than 50 researchers was awarded 250 hours of observing time during the James Webb Space Telescope’s first year and received a first batch of data in December 2022, with more coming in through January 2024.

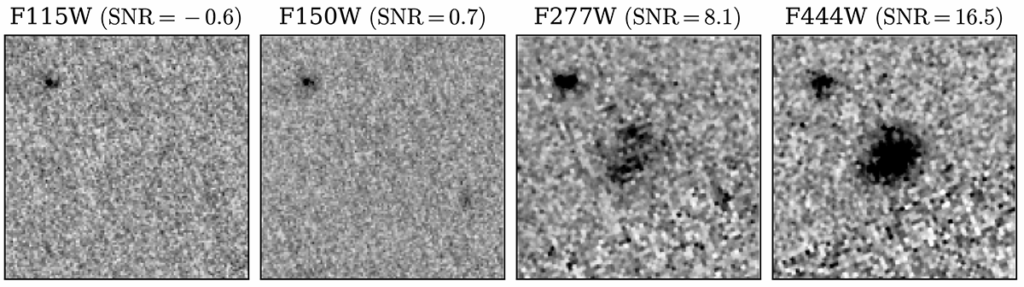

A dusty star-forming galaxy is hard to see in optical light because much of the light from its stars is absorbed by a veil of dust and then re-emitted at redder (or longer) wavelengths. Before JWST, astronomers sometimes referred to them as “Hubble-dark galaxies,” in reference to the previously most-sensitive space telescope.

“Until now, the only way we’ve been able to see galaxies in the early universe is from an optical perspective with Hubble,” McKinney said. “That means our understanding of the history of galaxy evolution is biased because we’re only seeing the unobscured, less dusty galaxies.”

This galaxy, AzTECC71, was first detected as an indistinct blob of dust emission by a camera on the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii that sees in wavelengths between far infrared and microwave. The COSMOS-Web team next spotted the object in data collected by another team using the ALMA telescope in Chile, which has higher spatial resolution and can see in infrared. That allowed them to narrow down the location of the source. When they looked in the JWST data in the infrared at a wavelength of 4.44 microns, they found a faint galaxy in exactly the same place. In shorter wavelengths of light, below 2.7 microns, it was invisible.

Now, the team is working to uncover more of these faint galaxies from the James Webb Space Telescope.

“With JWST, we can study for the first time the optical and infrared properties of this heavily dust-obscured, hidden population of galaxies,” McKinney said, “because it’s so sensitive that not only can it stare back into the farthest reaches of the universe, but it can also pierce the thickest of dusty veils.”

The team estimates that the galaxy is being viewed at a redshift of about 6, which translates to about 900 million years after the Big Bang.

Study authors from UT Austin are McKinney, Casey, Olivia Cooper (a National Science Foundation graduate research fellow), Arianna Long (a NASA Hubble fellow), Hollis Akins and Maximilien Franco.

Support was provided by NASA through a grant from the Space Telescope Science Institute.