In the early afternoon of April 8, 2024, The University of Texas at Austin will find itself in eerie darkness as the moon begins to block the light of the sun. In Austin, “totality” will begin at 1:36 p.m. and last less than two minutes. Just as students and staff are looking forward to the event, faculty members who study and teach about ancient cultures will be taking special note of the historic eclipse as their thoughts turn to our ancestors and what must have been going through their minds on such occasions. You may read about the Maya here and Native Americans here.

***

Have you ever been assigned a job that didn’t really turn out like you expected? Maybe it seemed pretty good at first glance, but then you started to regret the promotion. Please read on.

Heath Dewrell teaches myths and legends of the Near East in UT’s College of Liberal Arts Schusterman Center for Jewish Studies. His main focus is ancient Israel and the Hebrew Bible. Dewrell, who came to UT just more than two years ago, says people study the Hebrew Bible for very different reasons, and his purpose is to situate it in the ancient Near Eastern context, sandwiched between Egypt and Mesopotamia.

As for the Israelites, there is no word for eclipse in the Hebrew Bible, but the prophet Amos does say “the sun will be darkened on the day of the Lord.” The prophets of the books of Amos and Isaiah spoke about the “great day of the Lord” as a day of judgment. “They will say, on the day of the Lord, God’s going to come down and take care of the good people and the bad people, and you all are the bad people, so you don’t want the day of the Lord to happen,” Dewrell paraphrases. “We don’t know what the ancient Israelites would have called a solar eclipse, but some people have said that sounds a lot like a solar eclipse. If you go through the records for the time that Israel existed as a kingdom I think there was one solar eclipse in the several centuries of its history.”

In the Hebrew Bible, in the Book of Genesis, the sun and the moon are both said to be stuck in a dome. “The sky was a great big dome, and the heavenly bodies were just stuck in their places so that when the dome moved, they moved. The moon couldn’t go in front of the sun, so what in the world did they think was happening?”

Egypt was less interested in astronomy for astronomy’s sake. Inasmuch as they did delve into it, it was fairly late and under the influence of the Mesopotamians, says Dewrell.

Solar eclipses were among some of the most dangerous things out there."

Mesopotamians were much more obsessed with astronomy and omens, Dewrell says. “Some tablets are just big, long lists of astronomical events: If this happens, then that will happen. If there’s a lunar eclipse and the left edge is red, then that is bad news for the enemies of the king. If it’s red on the right side, it’s bad for the king.” He adds that some of these hypotheticals are astronomically impossible. “For example, a solar eclipse can only take place during a new moon. But they mapped out the entire realm of possibilities and impossibilities.”

“They got pretty good. It looks like they could actually predict when eclipses were going to happen, which was really impressive for say, 700 BCE.” Astronomical elements were not universally negative. Sometimes the objects were merely clouds. “They don’t have this conception that clouds are very close and stars are way off. They’re both up there. Sometimes a bad omen can be a good omen if it’s about the enemy. The general rule was if the astronomical event happens on the right side, it, something such as famine, was for the king and his country, and if on the left, was for the country of the enemy.

Omens weren’t limited to astronomical events: when they sacrificed sheep, they would look at the livers, which could have signs in them such as holes. They also looked at births, especially anomalous births, of both animals and people. Some kinds of omens they believed could be warded off. “If there was a goat born with two heads, you could do things to ward off the bad things that were going to happen.” But astronomical omens such as eclipses usually spelled bad news for the king or his family, and typically nothing could be done. “It’s going to happen,” he says. Well, almost nothing. And this is part that could be ripped straight from a Mel Brooks screenplay:

“This bad thing is going to happen to the king. So the Neo-Assyrians came up with this substitute-king ritual. In the next hundred days, this bad thing is going to happen to the king. They would take some random guy and go through all of these rituals. In fact there’s one letter in which it looks like the substitute king is actually doing king stuff, and the scholars back then are like, ‘Is he really allowed to make decisions?’

“The king would go off and be a farmer, the big event would pass, and then, as far as we can tell, they would kill the substitute king, and the farmer would become king again. Problem solved!”

It was horrifying, says Dewrell, “but brilliant at the same time.” “They really believed it was going to happen. It wasn’t like our horoscopes today — well maybe it’ll happen, maybe it won’t. They had to figure out a way around it. You can see the lawyering behind it: killing the guy fulfilled the prophecy. To me, that captures the best possible example of how the ancients viewed eclipses. They were omens. The fates of human beings were written onto the heavens. Solar eclipses were among some of the most dangerous things out there. It’s definitely going to happen. But you also see the lawyermanship: OK, it technically says this is bad for the king. If you’re not the king, it’s not going to happen to you. It’s going to happen to whomever the king is!”

Given how rare total eclipses were, it is amazing that they still had big long lists of contingencies.

... they would kill the substitute king, and the farmer would become king again. Problem solved!"

The Mesopotamians cataloged everything, Dewrell says. One of the reasons we know the really old languages like Sumerian, which was dead by the time most of the texts came out of the ground, is that the Mesopotamians have these lists of words. “They had all these tablets that are just, ‘Here’s the Sumerian word for this type of wood.’ They just wanted to get all the knowledge they could into writing, including observations about the heavens and what they meant.

Dewrell notes that when he writes about ancient astronomy, he uses “astronomy” and “astrology” interchangeably because for the ancients, they were the exact same thing. “The idea that an astronomer just observes where the bodies are moving, and an astrologer does something different — no, no, no,” he says. “They were using the bodies so that they could get the meaning from them and then go do something about it, and that doing something about it could mean making someone else king so you could kill him off.”

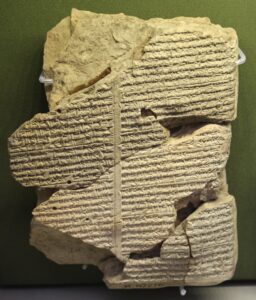

Astrologers were not on the fringe of society; to the contrary. “As far as we can tell, these were the most educated and smartest people in the ancient world,” Dewrell says. “The idea that an astrologer was some kook who writes newspaper columns — no. It took decades of education to write these tablets. These texts are written in some of the hardest-to-read Akkadian. Cuneiform is almost always hard, but they’re intentionally using the most difficult possible ways to write things down, so that only someone with the most rigorous types of training would have been able to access them.”

Dewerell, whose office is in Calhoun Hall in the six pack, is meeting up with colleagues on the South Mall to watch the eclipse. “I’ve seen multiple partial eclipses, but everyone I’ve met who’s seen a real one, a full one, has said it’s not even close.”

He enjoys camping. “One thing I love about it is looking up at the sky and saying, oh wow! This is what the ancients saw every night. No wonder they could track the movements of the heavenly bodies in ways that are hard for us. It was a tapestry. I’m really looking forward to this eclipse to see what they saw. That’s what I’m going to be imagining. I think of the ancients as my long dead friends. What did my long dead friends think about this?”