What are the dominant objects of your everyday life? Your phone? A credit card? A pair of sunglasses? If those were found 150 years from now by an archaeologist, would they be considered significant? Probably not. But they might take on significance if expertly filmed, animated and projected 16 feet tall or 120 feet wide.

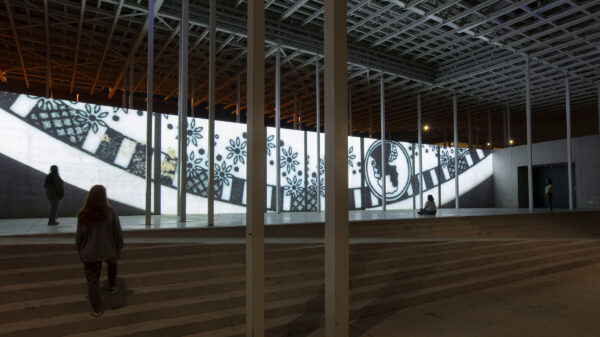

Such are the questions that arise when viewing a new art installation in Waterloo Park south of campus in downtown Austin. “Past Deposits from a Future Yet to Come” is a 27-minute video loop projected on the upstage wall of the three-year-old Moody Amphitheater, accompanied by an original soundtrack. It was created by two internationally acclaimed artists, both of whom are on the UT faculty, Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler.

***

Darkness falls in the park, and into a black void, a Wheat Penny slowly descends into view on the left side of the enormous wall, slowly spinning and tumbling as if an astronaut in zero gravity has lost their grip on it. In due time, shards of painted porcelain plates fall through the wide frame, spinning at different speeds and rotating in different directions. The picture slowly dissolves to colorful glass marbles, glass bottles, plastic toys, nothing to scale with anything else. A tiny fragment of comb might be projected, not 20 feet wide, but 90 feet wide, rendering detail at a nearly microscopic level.

During the showing of nearly 1,000 objects, we begin to recognize groupings: round things, blue things, rusty things, tools, things made of glass, iridescent things. And since many are shown more than once, we also make friends with recurring characters: the pink frog, the bullet, always moving faster than the rest, the rusty key to a Ford, the bent spoon.

For both the artists and the objects, it has been a long and interesting journey to this wall on Waller Creek. Hubbard, who was born in Ireland and grew up in Australia, earned her Bachelor’s of Fine Arts from UT in 1988. She was recruited to the Longhorn faculty in 2000 to lead a new program in digital photography and is now the William and Bettye Nowlin Professor in Photography in the Department of Art and Art History in the College of Fine Arts. Birchler, a native of Switzerland, joined the department in 2018 and is a professor of practice and fellow to the John D. Murchison Regents Professorship in Art.

The two met in 1989 as artists in residence at the Banff Center for the Arts in the Canadian Rockies, where they started to collaborate. Ever since, they have been an inseparable package deal — creatively, professionally and even academically: they applied to graduate school as a collaborative team and received the first joint master’s degree in fine arts in North America (from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design University in 1992), then an honorary doctorate from the same school in 2017. The married couple is known in the art world as “Hubbard / Birchler.” Their work on “Past Deposits…” began during 2020, but the real story long predates that.

Waller Creek, which runs south through the UT campus along San Jacinto Blvd., has been the site of extreme flooding for time out of mind, flooding made even worse with the impervious cover that comes with development. In the early 2000s, the city began taking action to control the creek along the mile that it flows through downtown. It began digging an enormous tunnel 26 feet in diameter from 12th Street to Lady Bird Lake. Any water above the normal creek level at 12th and Red River streets now drops through a massive inlet shaft and falls 70 feet into the underground tunnel, which empties into the lake.

It is standard operating procedure for the city to check for historical artifacts before beginning a major construction project. In the early 2000s, archeologists began digging in several locations in Waterloo Park, where the tunnel inlet is, and along Waller Creek. The teams uncovered and cataloged almost 1,000 artifacts dating from the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries.

In 2020, as the Moody Amphitheater was about to be constructed, the Waterloo Greenway Conservancy, a foundation partnering with the city of Austin to create a 1.5-mile trail along Waller Creek connecting six parks, invited Hubbard and Birchler to develop a work of art to activate the amphitheater in the rejuvenated Waterloo Park.

“As we began to research the site, we discovered just how much the grounds had been disturbed,” says Birchler. “The tunnel had demanded an incredible amount of earth removal. We realized that we needed to know more about the history of this site,” he says, “so as we always do, we tried to read as much as possible, get our hands on historic photographs, and we discovered that many of the artifacts found during the archeological digs had been cataloged.”

In the reports, the archaeologists used terms like “significantly disturbed deposits,” “redundant findings” and “objects of limited integrity.” “All of that just made us more intrigued because we are interested in everyday moments,” says Hubbard, “everyday people who get left out of the story.”

Despite the objects’ apparent insignificance, the archeologists had preserved them and moved them to the Texas Archeological Research Lab at UT’s J.J. Pickle Research Campus in north Austin. It took the artists three trips to locate the boxes among the 5 million other artifacts at the Raiders of the Lost Ark-like facility, but eventually they found them. “When the head of collections at the time, Marybeth Tomka, came out with the boxes, she was almost apologetic that we had spent all this time for these ‘objects of limited integrity,’” says Hubbard with a laugh. “She said, ‘Are you really sure you want to look at these?’ adding, ‘If you want to find anything of significance, you’ll have to go to the bottom of Lady Bird Lake because everything’s been washed away.’ So this idea of washing away became central in how we began to choreograph these objects.”

There were plates, marbles, bottles, coins, bullets, keys, and buttons — so many buttons. The objects offered a glimpse into the daily lives of people who lived and worked along the creek. The oldest one is thought to be a Catholic medal depicting the Virgen de San Juan de los Lagos from 1888, though there might be older artifacts, such as horseshoes and class jars, that can’t be dated accurately. The newest object? Perhaps a pink plastic frog toy from the 1950s.

“These were artifacts from an underserved neighborhood, says Birchler. This area didn’t even have garbage collection until the 1930s, “so even though these people served downtown, the city did not serve them. As a result of that, a lot of these deposits were just chucked down the creek. To get rid of your garbage, you burned it, buried it or tossed it in the creek.” Birchler adds that many of the objects also were thrown down outhouse toilets into the earth.

“During those years, that neighborhood was very diverse” says Hubbard, “consisting of small family businesses, seamstresses working out of laundry shops, women operating side businesses out of the home to make ends meet, and small carpentry workshops serving downtown.” Archeologists found numerous pennies. “Whichever family or families lived there, they saved their pennies. For one reason or another, most likely because of the flooding, these pennies were lost. It was a community where a penny meant something. You would not know that by looking at this place now, where everything’s a high-rise loft, with this new amphitheater, this park — none of that is visible anymore.”

No one had as much as looked at the artifacts since they were put in storage. Fortunately, because of the low interest, the two were able to borrow items and move them to their studio in East Austin to study and film them for more than a year.

“One of the most powerful attributes of this medium is scale,” Hubbard says. A child’s marble, when lighted and filmed in a special way, can become extraordinarily beautiful and huge — 16 feet tall — and become “planetary, like a solar system,” she says.

Asked about the division of labor, Birchler says that in addition to them engaging a small production team, “I’m definitely more involved in the technical aspect of things. In the late stages of editing, I’m more hands-on.” Hubbard adds, “I’m more about communication and how we should be choreographing these objects and the timing and the flow of things. I’m also thinking about the stories we want to tell with these objects. My background is in writing (she began college as a creative writing major at LSU), whereas Alexander comes from a much more classical academic training in painting, drawing and sculpture.”

But she adds, “We strive to reach what we call a third place or third voice in our collaboration. This ‘third place’ is not Alexander’s ideas with mine added on, or visa-versa; it’s a hybrid authorship and a creative process in which individual authorship disappears in order to arrive at a place neither one of us could have ever created on our own.”

The pair has had academic job offers elsewhere over the years, “but UT has always responded with strong retention offers and supported our research,” Hubbard says. That support has included allowing them time to produce and exhibit their work internationally and to attend prestigious artist residencies in Italy, Sweden, Ireland, England, Germany and Canada.

The video can be experienced with original music composed by Alex Weston — a soundtrack at turns haunting and whimsical that includes vocals, piano, strings and woodwinds. The video can also stand alone, simply accompanied by the park’s own soundscape of city noises, nature and the gurgle of the stream at the heart of the whole project. A QR code near the stage sends visitors to the Past Deposits website, and from there, after downloading an app and connecting to wifi, viewers can stream the soundtrack, synched with the video, over their phones.

Confirmation of the installation’s effectiveness has come in many forms. Since the park’s inception, Waterloo Greenway’s programming and public art is attracting an increasing number of visitors. “What’s so nice is that a wide range of people are interacting and responding,” says Birchler. “Families schedule their visits so that when the piece comes on, the kids just run right up to the stage! They run back and forth along the wall, trying to catch and touch all these objects.”

But perhaps no confirmation of the mesmerizing quality of the artwork has been more impressive than what occurred on one of the many nights Hubbard and Birchler spent testing the video on site. “It’s a park, so, you know, some young people go there to make out,” says Hubbard. “There was a young couple sitting on one of the cement walls, and I was walking near them when the young woman turned to the guy and said, ‘Would you stop kissing me? I want to watch this!’”

* * *

“Past Deposits from a Future Yet to Come” can be viewed at the Moody Amphitheater nightly until the park closes on evenings when shows are not being set up or performed. Check the schedule before going: https://waterloogreenway.org/past-deposits/?tab=viewing-schedule. The installation will be up at least five years, with the score performed live on stage annually.