Bill Moyers, B.J. 1956, a pioneer of thoughtful long-form television journalism who won two Pulitzer Prizes and more than 30 Emmys, died Thursday. He was 91.

Moyers grew up in the East Texas town of Marshall and was “called to journalism” at 16, when he went to work for the Marshall News Messenger. He began college at North Texas State, where he met Judith Davidson, B.S. 1956, on his first day of class. They married and both transferred to The University of Texas two years later. Moyers worked his way through UT — 40 hours a week — as a reporter for KTBC, wheeling around to various accident and crime scenes in a red station wagon called “The Red Rover.”

He graduated with a degree in journalism in 1956, then spent five years in the Baptist seminary including a year at the University of Edinburgh. Though he chose to return to journalism, this experience bespoke a breadth of interests and spiritual dimension that would infuse his life’s work decades later.

He was on the verge of beginning work on a Ph.D. at UT in 1959 when he received the call from then Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson inviting him to join his presidential campaign. When Johnson became vice president, Moyers was appointed deputy director of the Peace Corps, and when Johnson became president, he brought Moyers into the White House as his special assistant and briefly as chief of staff.

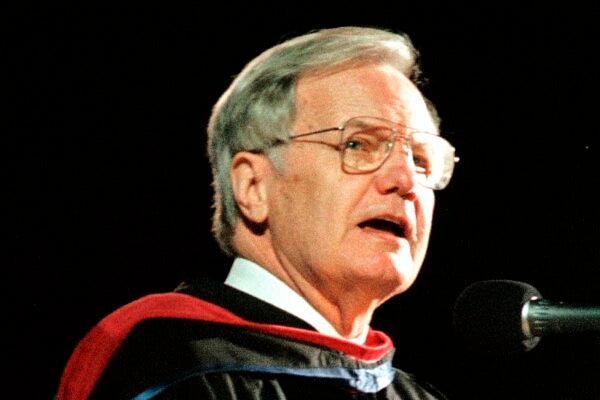

Moyers was extremely proud of his connection to UT and returned to campus readily, be it to participate in symposia at the LBJ Presidential Library, to accept the Distinguished Alumnus Award from the Texas Exes in 1986, to celebrate The Daily Texan’s centennial, or to deliver the commencement address in 2000.

There was something about this campus that created a river of energy from the streams and tributaries flowing here from other places...

In a lengthy interview he gave to UT’s alumni magazine, The Alcalde, in 2000, he called the Forty Acres “the place of my second birth.” Asked in that interview what made him think as a journalist he could do a six-hour TV series on the Book of Genesis, he said, “It never occurred to me that I couldn’t, and I trace that directly to my experience at The University of Texas. … It wasn’t until I transferred here that those ideas [journalism and the humanities] began to connect. There was something about the University in the ’50s that did not separate those. There was something about this campus that created a river of energy from the streams and tributaries flowing here from other places, so that Robert Cotner in history, and Gilbert McAllister in anthropology, and DeWitt Reddick in journalism, and Alice Moore in English were all talking about the same thing. They were talking about life and the life of the mind.

“Everything I did here seemed to connect both to every other thing and to the larger world,” Moyers continued. “All the strands came together. It wasn’t deliberate; it was just the atmosphere here. Willie Morris editing The Daily Texan was connected to the larger world of politics.” Moyers said that as his life unfolded, “what to the outside observer might seem to be eclectic” to him “was a unified theory of knowledge.” “Somehow, it is this nurturing here of the often-invisible connection of seemingly contradictory experience that I think has made my journalism different — not better than anybody else’s, not superior, but just different. And I’m grateful for that.”

It was as a Longhorn student that Moyers first read Joseph Campbell’s “The Hero With a Thousand Faces.” Thirty years later, his six-hour interview series “Joseph Campbell and The Power of Myth” would become one of his most beloved programs. “I don’t think anything I’ve done has had that much impact. People stop me today and say, ‘That changed my life.’” He co-edited the companion book with then-UT English professor and Plan II director Betty Sue Flowers, who went on to direct the LBJ Presidential Library.

He said that the Campbell series and others like it — “Genesis,” “Healing and the Mind,” “Close to Home” (inspired by his son’s struggle with addiction), “A World of Ideas” — were successful because they “struck the zeitgeist.” “They acted as a microphone, a magnifier of an otherwise modest series on a small network like PBS. I think that if that’s the case, it’s because, like The University of Texas, I don’t see things in isolation. Everything is connected somehow to how we live.”

Moyers twice was offered a chair on the UT faculty and considered moving to Austin, but by that time he and Judith had grown children settled in the northeast, which kept him in New York.

All the same, he said, “This [UT] is the place to which I do return. Someone asked me the other day, ‘You were here for the Daily Texan celebration. You’re here for this [a symposium]. You’re giving the commencement address in May. Why?’ And I said, ‘Because it’s the place of my second birth.’ I became intellectually awakened here. And it’s like the astronauts returning from space; they always head for Earth.

“And for me to return from the atmosphere of a vagrant sojourner, which is what journalism is — you go from place to place, restless, homeless — this is the Earth to which I always return. Somehow coming back here … I get more in touch with what I really am, who I really am, here than anywhere else. That’s because I was initially formed here. It’s like going back to your birthplace, even though somebody else lives there or even though it may be gone.”

He continued: “And the fact is that most of the landmarks of my youth are gone; that happens. But the Tower is still there. The Legislature is still there. The live oaks are still there, and there is a very palpable memory here, a living memory of what I felt and experienced.”

He recalled, “the exhilaration that greeted me, whether I was in Ginascol’s class on philosophy, or Cotner’s class on history, or Moore’s class on Chaucer, or McAllister’s class on anthropology, or Reddick’s class on journalism. I can see them in my head right now. I can hear their voices. How do you explain that? I don’t know how you explain that. Some people talk that way about their religious conversions. But I have that still-fresh sense of really coming alive here. Coming back here is to be put back in touch with that.”

Like The University of Texas, I don’t see things in isolation. Everything is connected somehow to how we live.

Beyond the numerous accolades he received for his wide-ranging work, Moyers was known for a remarkable generosity of spirit, and many people who came in contact with him tell stories such as this one:

Stephen Mason, B.A. 1990, recalls: “I was managing a restaurant downtown one year during the Texas Book Festival, and he came in for some lunch with his lovely wife. Not only was I slightly in awe, but I also knew that he was close friends with a couple of my former professors from UT. I immediately looked for an excuse to approach him and then patiently waited until his iced tea glass needed some attention. I may have even quietly lurked behind a potted cactus until his glass needed that refresh. An hour later, he and I were best friends.

“Two weeks later I walked into the office, and there was a package waiting for me on the desk from some unknown source in Manhattan. Inside was his most recent book with a thoughtful and sincere inscription. He’d taken the time not only to get my address, but somehow to learn that my name was spelled with a ‘ph’ and not a ‘v.’ He was that kind of guy.”